Fighting fires

One of the oldest Cape traditions

Published last week on Our Long Walk: How to win Afcon | My graduate course reading list | Check out my new personal website. | Thank you for subscribing. Please consider a paid sub.

We’ve had weeks of severe wildfires in South Africa’s Western Cape. In Franschhoek, not far from where I live, the mountains are black. Thanks to the efforts of firefighters, the damage to farms and buildings has been limited.

It helps, I think, to remember that fire has always been part of this landscape and that the struggle to contain it is older than most of our institutions.

On Christmas Day 1686, an entry in the Daghregister (the journal kept by the VOC commanders and governors at the Cape) records a hazy, smoke-laden day. People were burning “woods and surrounding fields” to force up fresh grazing for livestock.

Weather and wind as above, with a hazy air arising from the burning of woods and surrounding fields, practised both by the Khoikhoi and by the Company’s subjects in order to provide their cattle with fresh grazing; which, though beneficial to the farmer, is nevertheless found harmful to the inhabitants’ health, since most are afflicted by these harmful and poisonous fumes and fiery air with pains in the head, loins and belly, and also with the bloody flux, though not carried off [by death].1

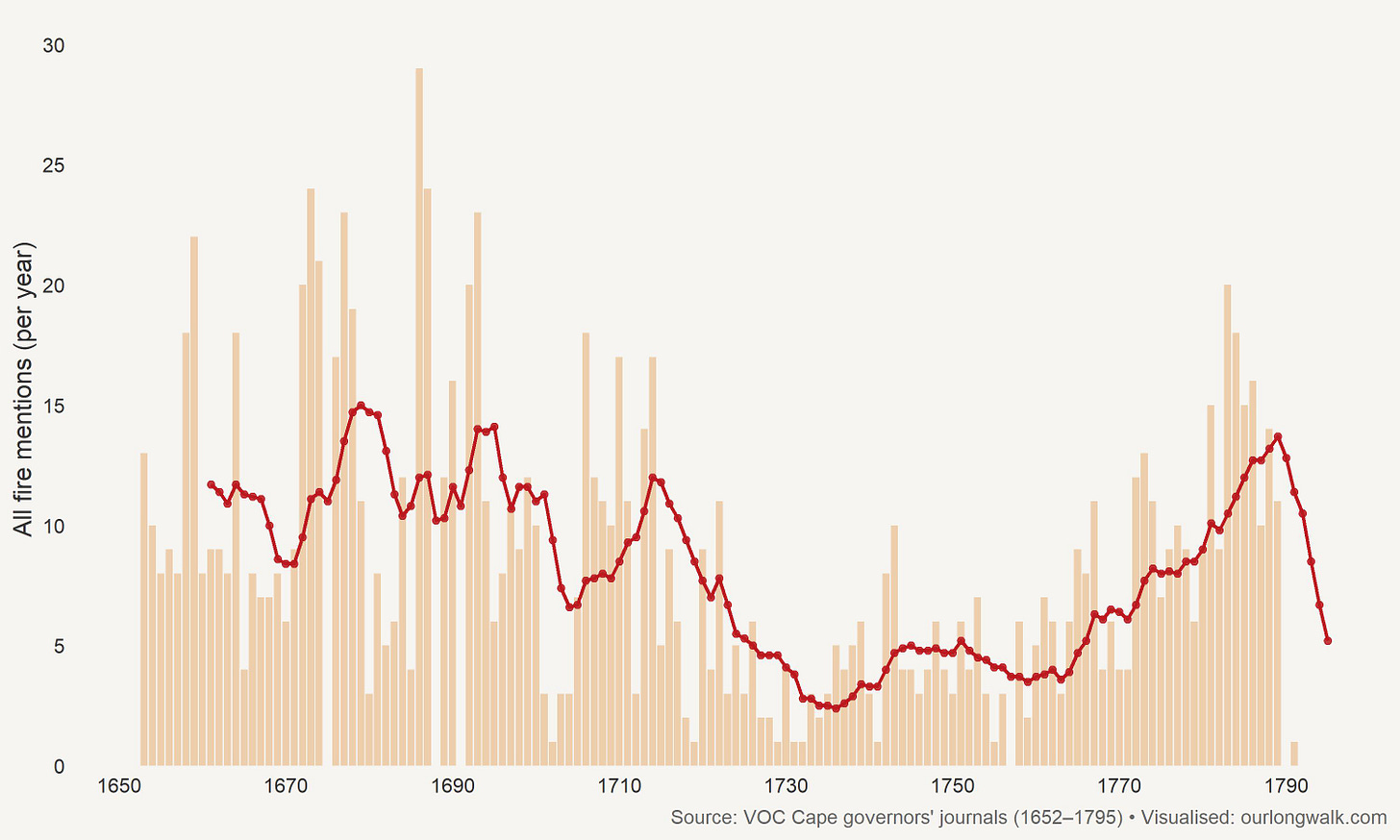

The Daghregisters are an extraordinary source. Now fully transcribed, they can be searched systematically in ways that would have been impractical even a few months ago. For this post, I used ChatGPT’s Pro version 5.2 to identify days on which fire is mentioned, then aggregated those mentions by year and season. There is an important caveat: the registers become less informative in parts of the eighteenth century, so a decline in “fire mentions” should not be read as a clean decline in fires themselves. What the series captures most reliably is the attention paid to fire in the official record.

Even with that caution, the patterns are suggestive. On average, there are about ten days per year in which fire is mentioned. Not all of these are wildfires, of course. Some are incidental references. But a skim of the flagged entries suggests that many do concern veld and mountain burning, rather than, say, a single domestic mishap.

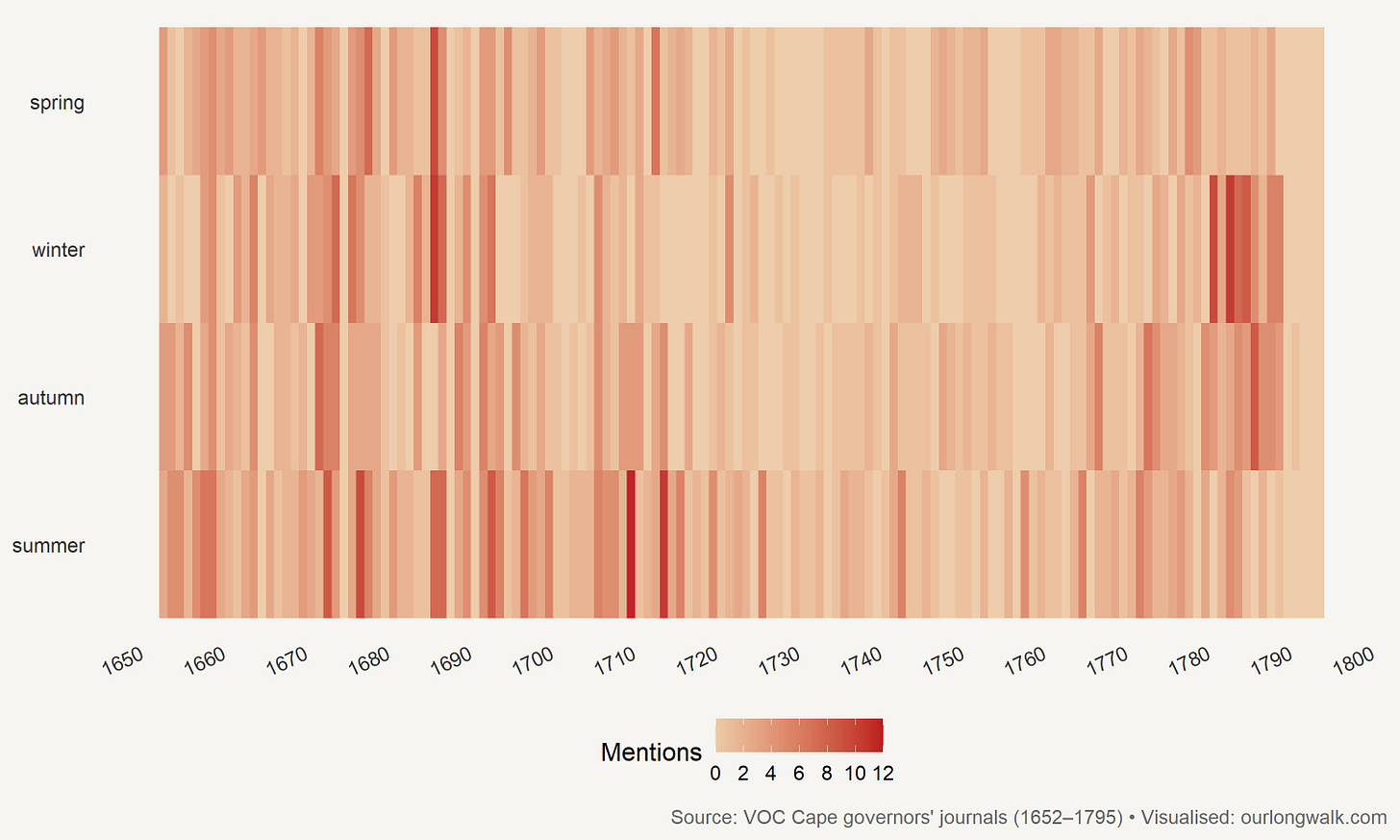

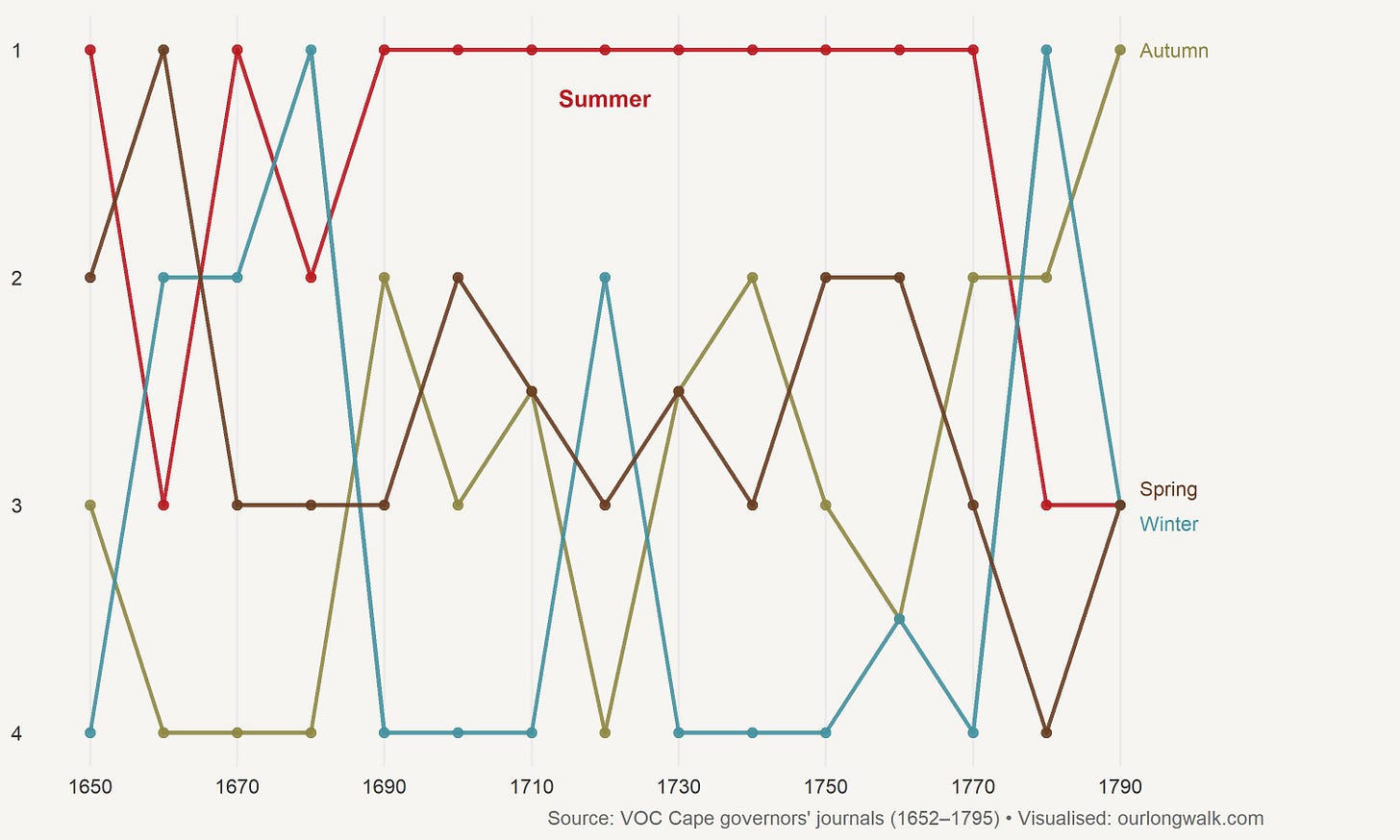

Seasonality is where the record becomes most interesting. Summer dominates, as one would expect in the Cape. But the winter spike in the 1780s is striking. That deserves a closer look: it might reflect an unusual run of conditions; it might reflect a shift in what officials chose to record; it might reflect something local, such as patterns of burning linked to grazing and land management.

Seen another way, the seasonal ordering remains familiar. Summer is the period in which fires are most frequently mentioned; winter is usually the least.

The Christmas entry was not the only episode that season. On 20 February 1687, the record turns from smoky inconvenience to catastrophe. A report from Stellenbosch, then still a fledgling community, describes two “grievous fires” that destroyed grain and enclosures, leaving “not the slightest thing” saved. The detail that matters, then as now, is that these were not lightning strikes. They were set deliberately and then escaped.

I am compelled, with the greatest sorrow of heart, to inform Your Honourable Excellency of the two grievous fires that occurred here on the 17th and 18th of this month, affecting the grain and the enclosures of the free burghers Antonij van Angola and Gerrit Cloeten, where everything has been ruined so that not the slightest thing was saved. Both arose (as far as I am aware) through their own recklessness in setting the veld alight; and the latter fire of Gerrit Cloeten was so violent on the 18th instant that, without God’s remarkable grace and the vigilance of the free burghers of Simons Valley, the three farmsteads standing there with all their grain (the fire having run over the mountains) would also have been reduced to ashes. Antonij’s loss amounts to well over three hundred, and that of Gerrit Cloeten to around one hundred muids of grain.2

Van der Stel had had enough. In response, he issued a placaat/proclamation, forbidding anyone to start a fire on farmland:

as we hereby strictly forbid anyone to set fire to any pasture- or cornland, whether ploughed or unploughed, fields, woods, shrubs or stubble, on pain that whoever is found to have violated this wholesome order—be he Company servant, free man or slave—shall for the first offence be severely whipped, and for the second be punished with the rope such that death follows; unless he has obtained our written permission to burn off his fields and has shown it to the officer before setting fire. (Thus resolved and decided, in the Castle of Good Hope, 19 February 1687, signed S. van der Stel … By order of the Commander, signed J.G. d’ Grevenb[roek], secretary, to Johannes Muller, landdrost, Stellenbosch.)3

There is a temptation to end with a neat line about history repeating itself. But the clear lesson is that many of the worst fires are not simply natural disasters. They are the result of human action. And as anyone can attest to who’s been in and around Franschhoek the last week or so, it can go wrong fast, especially in strong winds.

A big thank you to the firefighters, both professional and volunteer, who worked tirelessly under difficult conditions to contain and extinguish fires across the region. A special word of thanks to the Stellenbosch Fire Department, who were consistently quick to respond whenever I reported a fire, which happened more often than usual this year. The Stellenbosch community can be justifiably proud of your dedication and effectiveness.

“Weir en wind als boven met dampige lugt, ontstaande uijt ’t branden der bossen en omleggende velden soo bij de Hottentots als ’s Comp:s onderdanen gepractiseerd om daardoor aan hun vee versche weide te verschaffen, twelke hoewel voordeelig aan den akkerman, egter nadeelig aan der ingesetenen gesondheid bevonden werd, gemerkt die meerendeels door dese en gene schadelijke en giftige dampen en vuurige lugt met hoofd, lenden en buijkpijn, ook den rooden loop wel bevangen, dog niet weggerukt werden.”

“worde genooddrongen U:Ed:e Achtb:e met de meeste droefheid des herten te verstendigen de twee droevige branden alhier op den 17 en 18:e deses voorgevallen, omtrent het graan en de hocken van de vrijborgeren Antonij van Angola en Gerrit Cloeten, waar alles sodanig is geruineerd dat niet het allerminste is gesalveerd, beijde bijgekomen (soo veel bewust ben) door hun selfs roekeloosheid met het in de brand steken van het veld, en was den laeste brand van Gerrit Cloeten soo vehement op den 18:e passado, dat sonder Godes merckelijke genade en de wakkerheid der vrijborgeren van Simons Valleij, de drie aldaar staande hofsteeden met al hun koorn (door ’t over de bergen gelopen zijnde vier) mede in de asch souden sijn geraakt, de schade van Antonij bestaat in ruijm drij honderd en die van Gerrit Cloeten in omtrent honderd mudden graen.”

“gelijk wij wel scherpelijk verbieden mits desen, geen weij of koornlande, beploegde op onerploegde velden, bosschen, struiken of stoppelen in brand te steken, op pene dat die bevonden word dese onse heilsame ordre te hebben overtreden, hij zij Comp:s dienaar, vrijman of slave, voor d’ eerstemaal strengelijk gegeesseld, en voor de twedemaal agterhaald werdend met de koord gestraft te werden dat ’r de dood navolgt, ’t en ware hij onse schriftelijke permissie om sijn velden te mogen afbranden verkregen, en deselve an den officier voor en aleer hij die komt antesteecken vertoond hadde (Onderstond, Aldus gearrest:d en besloten, In ’t Casteel de Goede Hoop, den 19:e Februarij 1687, en was getek:d S: Vander Stel, … Ter ordonnantie van den E: H:r Commend:r, en was get:d J:G: d’ Grevenb:k Secrets: Stellenbosch, An Johannes Muller Landdrost.”

I concur with the idea "; it might reflect something local, such as patterns of burning linked to grazing and land management." My own experience of controlled Fynbos veld burning by farmers in the Western Cape was that it was practiced in later-winter/spring to 1) dampen/prevent runaway fires, and 2) allow last seasonal rains over the burnt veld to foster new growth. This may have differed from the indigenous way and hence reflect dominance of settled pioneers in the burning regime.

Have you noted the insightful decisive 'dip' (generally cooler) in the trend during the middle 1700's - inferred by the longer term climatic trend of "the Little Ice Age"?