How to win Afcon

And boost economic growth

Published last week on Our Long Walk: Why sports betting is taking off | Can everyone in the world escape poverty? | Thank you for subscribing. Please consider a paid subscription.

Last night, Senegal beat Morocco in a classic Afcon final. As always, the African Cup of Nations delivered memorable moments on and off the pitch, from Patson Daka’s awkward celebration for Zambia to the DR Congo superfan who stood motionless throughout his nation’s matches as a tribute to Patrice Lumumba.

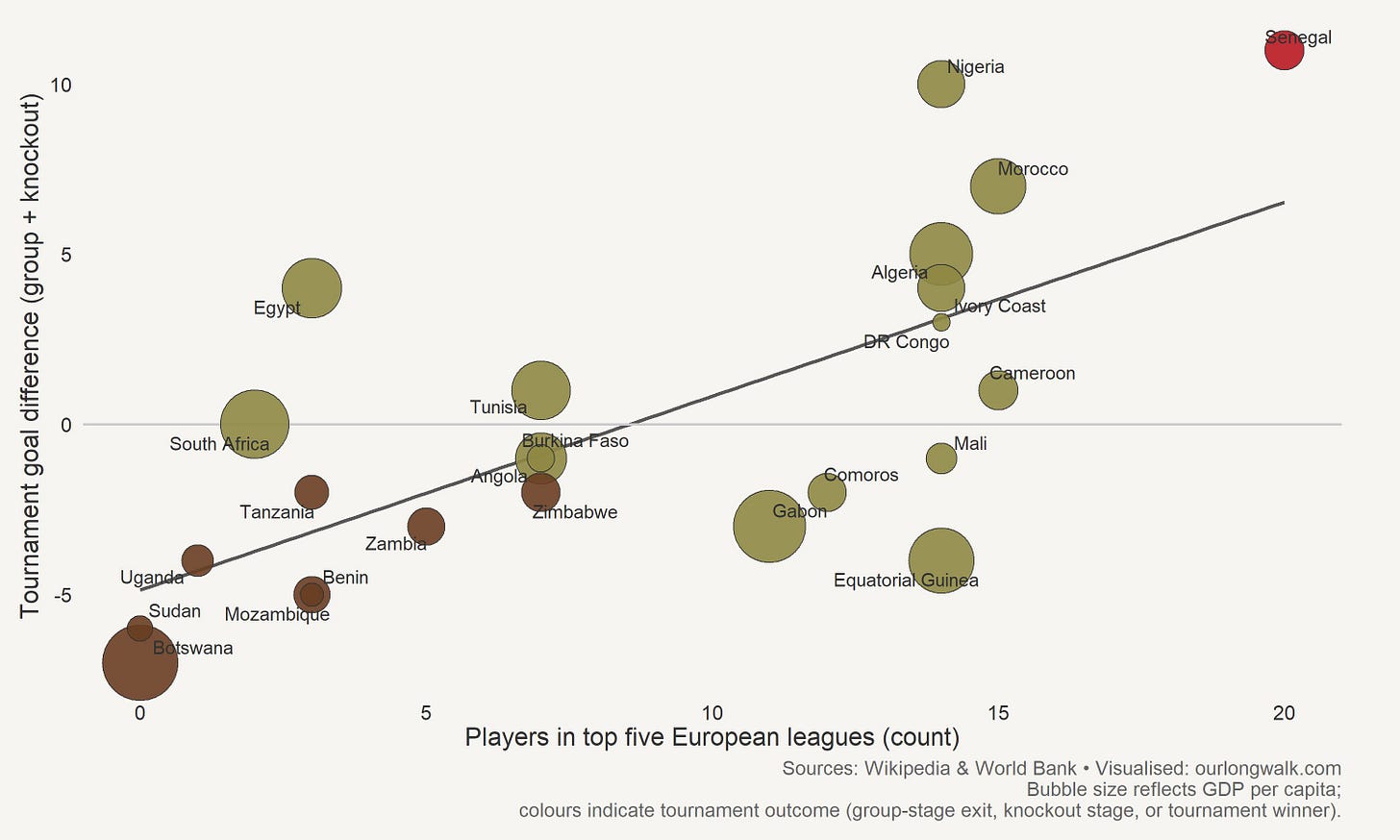

But while the tournament was entertaining, it was also a lesson in economics. Consider the graph below.

Along the horizontal axis is a simple count: how many players in each Afcon squad earn their living in one of Europe’s “Big Five” leagues (England, Spain, Germany, Italy and France). Along the vertical axis is an equally blunt performance measure: goal difference across the tournament, group stage plus knockouts. The relationship is positive. Teams with more Big-Five-based players tended, on average, to outscore their opponents by more. Roughly speaking, adding two such players is associated with about one extra net goal across the tournament. There are exceptions – Egypt, with a strong local league, can do a lot with relatively few Europe-based players – but no team with fewer than eight Big-Five players reached the knockout stages.

One correlation from one tournament does not make an academic paper. Goal difference can swing on a penalty or a red card, and the scatter plot cannot settle causality: strong teams may simply produce players who get signed by Europe’s best clubs. Still, the hypothesis is plausible: repeated Afcon success requires a core trained and tested in the steepest learning environments. Economists have tested that idea at scale. The economists Berlinschi, Schokkaert and Swinnen (2013) model player skill as the product of talent and the quality of training and competition at the club, with bigger gains when the gap between the destination and home league is larger.1 Empirically, they do not just count migrants. They build a “migration index” that weights each player by the strength of the foreign league and the division in which he plays. Moving from a weak domestic league to a top European league is not the same human-capital shock as moving sideways to a league of similar quality. They find robust support for the view that migration improves national-team performance, especially for countries with weaker domestic leagues, precisely because the quality gap is larger.

Their most persuasive evidence is when they exploit changes in migration restrictions after Bosman – the 1995 European Court of Justice ruling that effectively liberalised player mobility within Europe by removing transfer fees for out-of-contract players and loosening constraints on EU-player quotas – to get closer to a natural experiment. Their difference-in-differences exercise compares performance just before Bosman (1994) with performance when restrictions were lower (2010), and asks whether countries with larger increases in the migration index also saw larger improvements. They find that a ten-percentage-point increase in the migration index is associated with an improvement of about five places in the FIFA ranking. That is the kind of effect that turns a quarter-finalist into a perennial contender. And football migration is not a “drain” in the usual sense: players can compete abroad and still report for national duty, so the national team can benefit from foreign training without losing access to the talent.

There is a crucial nuance, though, and it matters for how we read our Afcon graph. Being abroad is not the same as playing abroad. A player who signs for a big club but sits on the bench does not absorb the same intensity as a regular starter elsewhere. In a new Scientific Reports paper, Lu and co-authors (2025) use match-level data on Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean players in Europe from 2000 to 2024 to make this point clearly.2 FIFA rankings are correlated with expatriate players, particularly those in the Big Five, but the mechanism runs through appearances and minutes. Playing time is the key mediator: expatriates matter insofar as they translate into actual minutes in high-level matches, not merely contracts and passports. As Arsène Wenger put it, talented youngsters can waste their time on the benches of top teams instead of gathering experience on the pitch.

Up to this point, it is tempting to reduce the lesson to a simple prescription: export your best players. But the deeper point is about the kind of market you have – at home and abroad – for allocating talent to its highest-productivity use. Europe’s Big Five leagues are not just “good” leagues; they are open, intensely competitive labour markets. Clubs recruit globally. Players move to where training is harder, coaching is better, analysis is deeper, and competition is relentless. The result is a frontier environment in which skills are produced faster. In economic terms, this is a thick market with strong selection and strong learning-by-doing: better matching between workers and organisations, and faster skill accumulation through repeated high-stakes tasks.

This is where the football analogy becomes more than a metaphor. The economists Glennon, Morales, Carnahan and Hernández (2025) study European football clubs as organisations competing for scarce talent.3 They exploit country-level rules that determine how many “immigrant” players clubs can deploy, and use rule changes as instruments to identify the causal effect of employing skilled immigrants on performance. They find that more immigrant players in the starting line-up improves performance, and not by a trivial amount: each additional immigrant player raises a club’s goal-difference margin by about 0.17 in their setting. The mechanism is straightforward. Immigrants tend to raise average talent, but they also widen the menu of strategies and combinations a team can deploy – organisational flexibility that is difficult to replicate in other ways.

The central story is less about the origin country “benefiting from migration” and more about the receiving organisation benefiting from openness, because openness expands the talent pool and improves matching. That feedback can raise the standard of the league and, indirectly, the skills of local players who compete within it. The same logic applies in business and academe: when firms or universities face barriers to hiring globally, they narrow the market and slow the diffusion of frontier methods. Protection can look compassionate in the short run, but it often carries a productivity cost that shows up later.

That claim is easy to assert and hard to prove. Yet we have unusually persuasive evidence from outside sport. Economists Beerli, Ruffner, Siegenthaler and Peri (2021) study a Swiss reform that granted European cross-border workers freer access to the labour market, affecting regions near the border more strongly than regions further away.4 The familiar fear is that foreigners arrive, wages fall, and jobs are “taken”. Their findings go the other way for skilled natives. The reform increased foreign employment, but it also expanded and improved the performance of skill-intensive incumbent firms, attracted new firms, and raised wages of highly educated natives. The key is labour demand: when firms can access scarce skills, they expand, invest, innovate, and create new roles – often complementary and managerial positions – that natives move into. What looks like “competition for jobs” in a static picture becomes “expansion of opportunities” in a dynamic one.

This is the point at which South Africa becomes both the obvious example and the uncomfortable one. We have high unemployment, so we build labour-market rules meant to protect South African workers by making it hard to hire non-South Africans. In football, the Premier Soccer League does something similar by limiting clubs to five non-South African players. The intention is understandable. But the evidence above suggests a counterintuitive possibility: restrictions designed to protect local labour can, under plausible conditions, harm it by making firms less competitive. If a firm cannot hire the specialist it needs, it may not scale, innovate, or win contracts; over time, that can mean fewer jobs, not more. In football, a league that limits the import of high-quality players may lower its standard, thinning the learning environment for locals. The short-run gain – more roster slots for locals – can come at the cost of weaker competition and slower skill formation.

What does this mean for Bafana Bafana? The PSL is one of the stronger leagues outside Europe. That is a blessing: it retains domestic talent, funds better facilities than many African leagues can afford, and offers professional careers that do not require an early gamble abroad. But it can also be a constraint, because a comfortable domestic league can reduce the incentive to seek harder environments where skills grow faster. And if the league restricts foreign players, it may dampen one of the simplest ways to raise standards at home: importing competition. If we care about the PSL as a development platform, the relevant question is not “How do we reserve places?” but “How do we raise the level of weekly competition?” That may require more openness, not less.

The implication is not that South Africa should throw open every gate without regard to unemployment. It is that we should be honest about trade-offs. In the economy, we should lower frictions that block firms from hiring scarce skills where those skills complement local labour and raise the productivity of whole teams, because a less productive economy is not a worker-protecting economy; it is an economy that struggles to create jobs and raise wages. In football, we should treat international exposure and domestic competitive intensity as deliberate development strategies rather than accidents. That means making it easier for young players to move earlier to demanding leagues where they will actually play, valuing minutes over glamour, as Lu et al. stress, and reconsidering whether the PSL’s foreign-player restrictions are limiting the league’s ability to function as a high-pressure learning environment for South Africans.

How to win Afcon, then, is not a mystery of “passion” or “pride” or just about appointing the “right” coach. Success is determined by the teams that connect their best talent to the steepest learning environments. Similarly, countries that allow firms to recruit scarce skills, combine them with local capability, and compete in thicker markets are more likely to build the kind of productive economy that can create jobs sustainably. The hard part is the counterintuitive part: sometimes the policies that look like protection are the ones that keep you stuck, on the pitch and off it.

An edited version of this article was published on News24. The image was created with Midjourney.

Berlinschi, R., Schokkaert, J. and Swinnen, J., 2013. When drains and gains coincide: Migration and international football performance. Labour Economics, 21, pp.1-14.

Luo, L., Tang, Y., Li, X., Sun, G., Guo, E. and Xu, H., 2025. East Asian expatriate football players and national team success: Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean players in Europe (2000–2024). Scientific Reports, 15(1), p.3707.

Glennon, B., Morales, F., Carnahan, S. and Hernandez, E., 2025. Does employing skilled immigrants enhance competitive performance? Evidence from European football clubs. Management Science, 71(7), pp.5746-5766.

Beerli, A., Ruffner, J., Siegenthaler, M. and Peri, G., 2021. The abolition of immigration restrictions and the performance of firms and workers: evidence from Switzerland. American Economic Review, 111(3), pp.976-1012.

Was wondering why then the difference why South Africa Rugby team does so well and have dominated the world rugby scene as compared to soccer. Could SA soccer failure also due to poor management?

Agreed. True in every walk of life and speaks to merit as the only criteria. That's why DEI and ESG will never work for fools the employ these standards.