Twenty years at Stellenbosch

How things have changed

Published last week on Our Long Walk: Newspapers that write history | Podcast with Xolela Mangcu ($) | Three lessons from the 18th-century Cape Colony ($) | Thank you for subscribing. Please consider a paid subscription.

As this post lands in your inbox, I will welcome the Economics 281 students for their first class of 2026. It will be exciting – as it always is – but also nostalgic. This class marks twenty years since I walked into my first lecture room to deliver a first-year lecture. I don’t really remember that first lecture, though I’m pretty sure I was both scared and naively overconfident. Twenty years later, I still feel that quickening of attention before the first class.

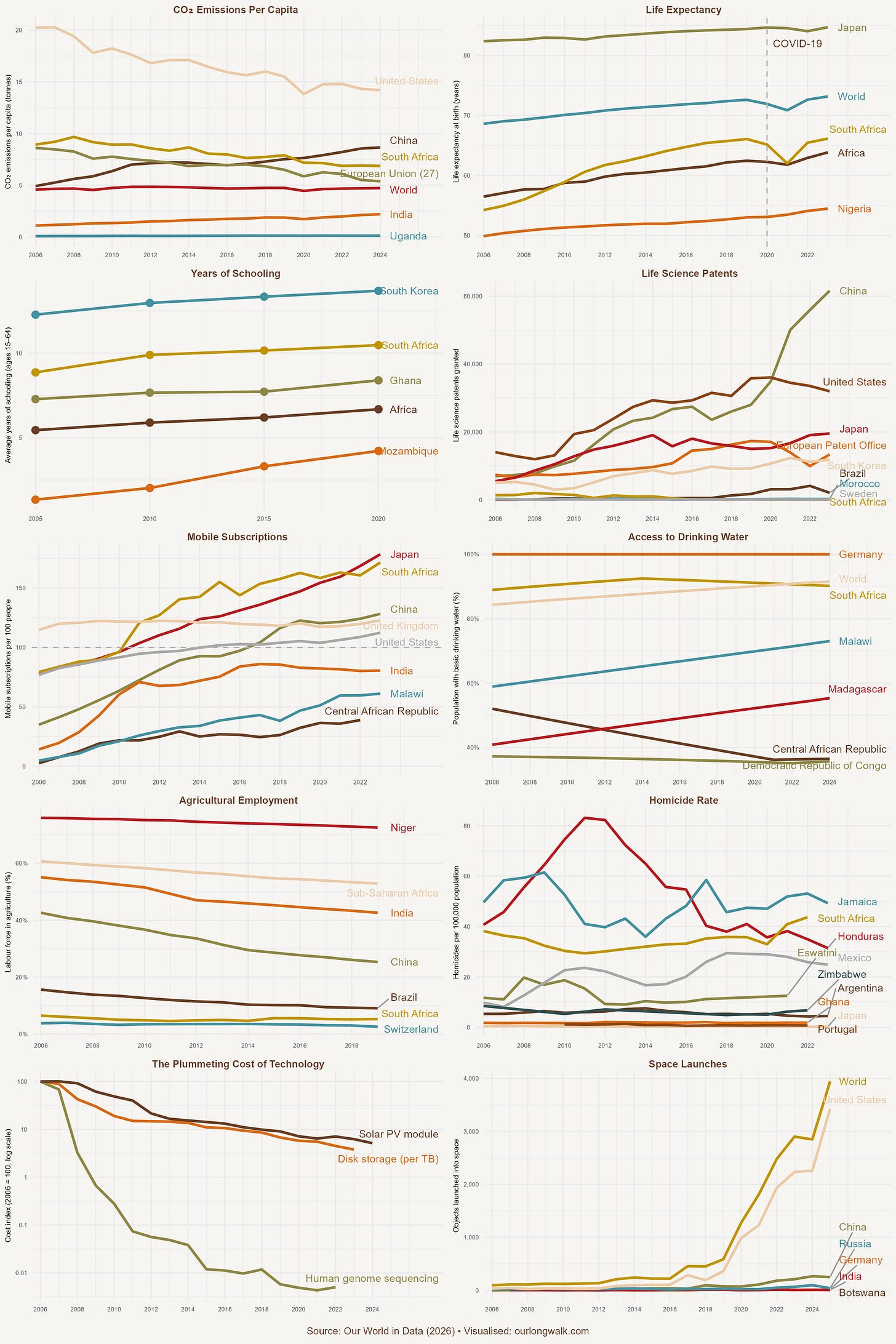

What has changed in these twenty years? The world, for one. Because these things are not reported in daily news, I’ve plotted ten graphs to show by how much, all beginning in 2006.

Let’s start with CO₂ emissions per capita. The United States and Europe have been trending down, which matters because it shows that living standards can be decoupled from emissions. China’s rapid industrialisation pushed per-capita emissions up to around European levels. South Africa remains high relative to the world average – a legacy of coal and heavy industry. But the direction of travel is clearer than it was twenty years ago. The technologies that make decarbonisation feasible are improving fast, and the pace of clean-energy deployment suggests emissions can peak sooner than many once expected. Meanwhile, most indicators that people experience directly move the right way. Life expectancy continues its long rise, with COVID-19 visible as a sharp interruption rather than a permanent reversal. South Africa’s curve is a story of large gains, a pandemic setback, and recovery. Schooling inches upward too, almost everywhere, even if the hardest work now is less about years enrolled and more about what children learn.

In short, across almost all dimensions humans care about, the world has become more capable and more connected. Innovation has shifted to the East – China’s surge in life-science patents is the headline – but it also reflects a wider diffusion of scientific capacity. Mobile subscriptions rise from scarcity to saturation, reshaping markets, information, and coordination. Access to drinking water improves for many, though progress remains uneven where states are weak. Agricultural employment continues to fall as economies urbanise, a marker of structural change that, when managed well, lifts productivity and incomes. Homicide rates is perhaps the only exception; death by murder remains frighteningly high in parts of the world, including South Africa. My conclusion: violence as a topic of inquiry deserves much more attention from economists.

One thing that was different in 2006 is how open the world was: it was generally accepted that more trade, cheaper movement of goods and ideas, deeper integration was pivotal for rising prosperity. Despite some well-publicised protests, globalisation felt less contested. The language of win–win was generally accepted at the centre of policy debate. It was in that mood that I was appointed as a trade economist.

Although I, too, believed in the importance of trade, I was never a great trade economist. I did manage to write a few papers on infrastructure, trade in services, and tourism – some of which later became my most cited work. It was a useful apprenticeship: I learned to identify gaps in the field that my vantage point from the southern tip of the poorest continent could see more easily. It also made me think much harder about the limits of data – and the gap between what we might know and what we could know. But an unexpected encounter with an economic historian, around 2007, proved pivotal. I’ve written about it on my (new) website, so I won’t repeat the full story here. The short version is that I stumbled into a field at the right moment. African economic history began to blossom just as I was looking for questions that felt both academically interesting and empirically possible. I have been fortunate in the people around me: supervisors and senior colleagues who were generous with their time and honest with their criticism. I travelled, presented at conferences, and met scholars that were kind and generous with their advice and resources. (One very good reason to choose economic history as a subdiscipline in economics.)

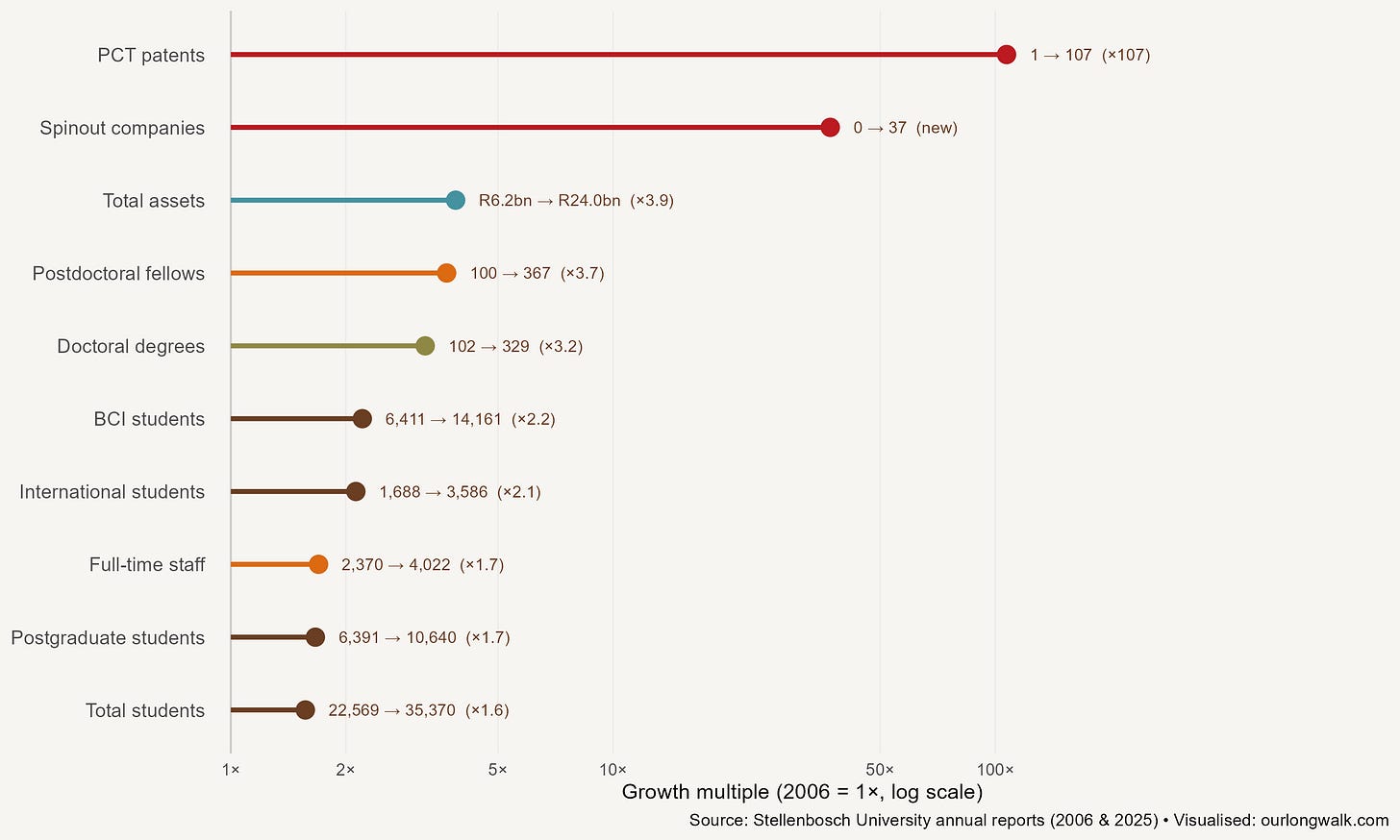

Over the last two decades, Stellenbosch University has also changed considerably. Chris Brink was still rector when I joined; Deresh Ramjugernath, three rectors later, started his tenure last year. The numbers in the figure above make the improvement clear. Total student enrolment rose from 22,569 in 2006 to 35,370 in 2025. Postgraduate students increased from 6,391 to 10,640. Full-time staff grew from 2,370 to 4,022. International students more than doubled, from 1,688 to 3,586. Research intensity is where the change is most visible. Doctoral degrees awarded increased from 102 to 329, postdoctoral fellows from 100 to 367, and total assets from R6.2 billion to R24.0 billion. Innovation metrics, read cautiously, show the most improvement: PCT patents from 1 to 107 and spinout companies from 0 to 37. These numbers suggest an institution that has become more research-focused, more international, and more serious about translating knowledge into practice.

The university also sits at an interesting nexus. If quality continues to improve, I expect we will attract more students from outside the Western Cape and outside South Africa. But demand is not enough. Funding, housing, and labour laws all matter, as do the administrative frictions that can derail the productive work of such a large institution. Pressures on universities are also not unique to us. My confidence is not that obstacles disappear, but that institutions that keep investing in quality and credible governance – and frontier technologies – remain attractive even in turbulent times.

The economics department, my home for the last two decades, has changed with the times. I don’t have a neat series of student numbers, but the faculty has almost certainly more than doubled. It is also younger and more diverse in method and interest, with several new projects taking shape. We also plan several large initiatives; I’ll write more when they are ready to be shared properly.

What we teach has changed too. We still teach core micro and macro, but we now teach fields that were peripheral in 2006: behavioural economics, industrial organisation, and data science, to name a few. Economic history has transformed too. The reading list I recently posted is evidence of the new datasets, new empirical strategies, and new questions.

What will the next twenty years look like? Who knows. My guess is that we underestimate the impact of artificial intelligence, both on the global economy and on universities and research. Regular readers will know I’m an AI optimist. Over the last month or so, my belief in what these tools make possible has increased again – partly because they are improving, but mostly because the effects that matter are cumulative: reading faster, coding faster, translating faster, testing ideas faster. That changes productivity. It changes what we ask students to do. Most importantly, it changes the questions we can ask, and answer.

Today I’ll tell the students that three things can be true at once. Terrible things are happening in the world. We live at the best time in history. And the future can be brighter still. I hope that, as always, my class will inspire them, even in a small way, to help build a better world.

I became a bit nostalgic when I read about the US of earlier days as touched upon by you. My own first US encounter was actually much longer back; 1974! Never had the honour to study economics there (that I did at Kovsies), but in 1974 Stellenbosch and the varsity were indeed what will almost be unthinkable today. My faculty was Engineering, probably the newest complex "on campus" at that time. I use the terms "on campus" in quotes, since it surely then was far from what was actually regarded as on campus at that time. From Simonsberg residence, it took a forever getting there on foot. Classes started at 08:00, every day. I envied the few students with cars, and also envied the studends who could mingle in the old part of the campus in buildings which were mostly historic, with much more laughter and relaxed attitudes among students who were not experiencing the the almost full-day grinding study programme of engineering students. When I now visit Stellenbosch on the odd occasion, I find it hard to find a definitive "campus". But that is of course the manifestation of the growth you plotted. To the US's credit, and especially the Economics Department's, I can attest to the fact that I employed more than one excellent graduate in economics from the US over the years. If your own work is a reflection of the standards still maintained in at least the Economics Department in general, then I have much confidence that my favourite discipline will continue to be relevent, even in the Age of AI...