When historians ignore economics

Humanities students fail to recognise the remarkable progress we've made, to the detriment of future generations

This is a free post from Our Long Walk, my blog about the economic past, present, and future of South Africa. If you enjoy it and want to support more of my writing, please consider a paid subscription to the twice-weekly posts that include my columns, guest essays, interviews and summaries of the latest relevant research.

For many years I gave a guest lecture to second-year History students at Stellenbosch. It usually followed the National Budget Speech by South Africa’s Minister of Finance. The purpose of the lecture was to distil the budget for humanities students enrolled in a course on the history of wealth and poverty, from ancient times to the present.

It was a lot of fun. I would, of course, start with the big picture: the dramatic increase in our living standards during the twentieth century – I’d show them a version of the graph below – and ask the students why they think we’ve seen such remarkable progress in the last century or two.

Their reaction was both expected, because it was the same year after year, and alarming. No, they would answer, there had been no increase in living standards over the last century. ‘Just look around you’, many would say. ‘Are you blind to the inequalities of our society?’

A single graph (using a much-maligned measure) failed to impress them, so I would have to explain that, sure, poverty is a blight on society, here and elsewhere. Still, we have made massive progress in reducing the number of people below the poverty line. To convince them of this, I would show a version of the following graph, which presents the population distribution at different poverty thresholds for the entire world, from 1820 to 2018. 80% of the world, I would tell them, lived on less than $2 a day in 1800, basically just above subsistence. Today that is 8%. (Also, today we are 8 billion people compared to the 1 billion back then.) That is a truly remarkable transformation.

This would usually convince enough of them that we are indeed living at a unique time in human history when most of us do not have to worry about where our next meal will come from. I would then go on to explain that this was because of the two lessons we had learned, best summarised by the economic historian Joel Mokyr: that we should use our knowledge of nature – some might call this science – to make ourselves more productive, and that we should use the surpluses we generate through our productivity to the benefit of everyone.

Yet what always surprised me was the profound sense of unease in the classroom. This unease was a consequence of a message that had been drilled into them by all their humanities lecturers: that the rich have become rich through expropriating land or labour, a belief that wealth was not the product of innovation and hard work but rather the result of exploiting resources and people.

I was astounded that, in my brief class discussion of the causes of the Industrial Revolution and the technological innovations that followed, students could only note the exploitation of the English workers or the exploitation of those in the British colonial empire. They failed to note the mechanical skills of English workers, for example, or the high number of informal networks that explain Britain’s lead. And they know little about the remarkable increase in worker wages that followed the IR, in England and, later, in Europe and the United States and, later still, elsewhere, the result of new scientific discoveries and associated technologies like the Haber-Bosch process that now provide nutrition for more than three billion people, or the creation of penicillin, saving millions of lives, or the transistor that connects me to the world (and to you)?

I soon discovered that their hostility towards ‘progress’ was a function of their training in the humanities. History students, at least at the second-year level, had almost no exposure to the optimistic science of economic history. They had a zero-sum mindset – that for me to win, you need to lose – and found it very difficult to fathom that, through trust, cooperation and exchange, we can all live wealthier, healthier and, yes, even more meaningful lives.

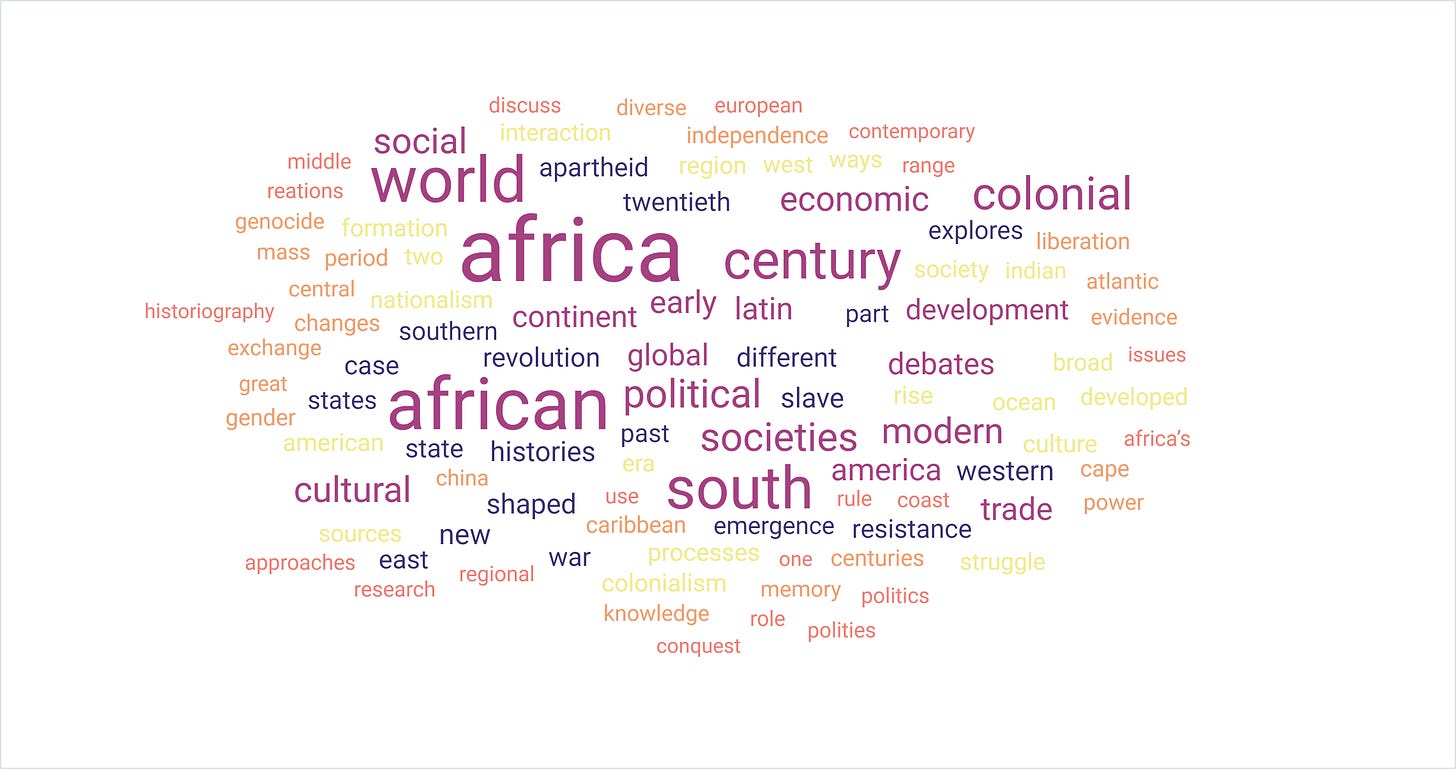

Sadly, this is true across South Africa. I downloaded the work programmes of all undergraduate History courses at the top South African universities, and created a word cloud of the course descriptions.1 (I excluded words like ‘course’, ‘students’, and a few others.) Notice the emphasis on systems of extraction – colonisation, slavery, apartheid, war, even genocide – and themes such as power, resistance and liberation. Of the 70 course descriptions, three included the word ‘science’, two the word ‘technology’, and one the phrase ‘Industrial Revolution’. Not a single one included the word ‘progress’.

Contrast that to the word cloud of the intro and epilogue of my book, Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom. I don’t think it is asking too much that every undergraduate History student be exposed to the two most important lessons from history.

This is, of course, not a uniquely South African problem. Globally, the humanities are pushing against the idea of progress. That is why some, like Tyler Cowen and Patrick Collison in a 2019 piece, have argued for a new study of the past: Progress Studies, a dedicated field to understand and accelerate the advancement of society. Innovation is not inevitable. Progress Studies, they argue, would investigate the factors contributing to successful innovation ecosystems, including the roles of people, organisations, institutions, and cultures, aiming to derive policies and practices that could foster further advancements. Michael Magoon, on his blog From Poverty to Progress, defines Progress Studies as ‘the systematic study of history, both recent and ancient, to develop policies and practices that maintain and, if possible, accelerate human material progress’. Jason Crawford, writing at The Roots of Progress, explains why it is important:

The progress of the last few centuries – in science, technology, industry, and the economy – is one of the greatest achievements of humanity. But progress is not automatic or inevitable. We must understand its causes, so that we can keep it going, and even accelerate it.

If students in the humanities are not exposed to these ideas, we risk fostering a skewed perception of history, one that undervalues human cooperation and innovation. This matters: it is often these students that end up in think tanks, NGOs or government, influencing policy. And as advances in artificial intelligence are quickly changing society, understanding the role of science and technology in improving our lives is crucial to building a future where progress is a shared and achievable goal.

To avoid this one-sided view of history, History departments would do well to incorporate more economic history texts that acknowledge both the triumphs and trials of the past into their curriculums. Yet, given the resistance to these ideas within the humanities, I don’t expect this to happen soon.

I’ve not been invited back to give the guest budget speech lecture for the last two years. The next generation of historians trained at Stellenbosch is unlikely to fully grasp progress’s impact on shaping a better future, to the detriment of all of us.

An edited version of this post appeared (in Afrikaans) in Rapport on 10 March 2024. The image was created using Midjourney v6.

In no particular order: Rhodes University, University of the Witwatersrand, Stellenbosch University, University of Cape Town, University of Johannesburg, University of the Free State, University of South Africa, and the University of the Western Cape.

I think your aspiration for two-sidedness for history departments might go over better if it was built around a shared interest in understanding accurately what each side is saying--but also in not trying to slip around both fundamental differences in perspective and in genuine disagreements about key points. For example, in South Africa particularly, at least some of what you've encountered from history students, humanities faculty and so on is informed by several strains of Marxist inquiry, which I think actually very much recognize the overall growth of wealth, the general transformation of the material conditions of human societies, etc., and see those changes as important precursors of the future political transformation that they hope for, but they would argue that trying to decouple exploitation and material improvement is missing the point in a fundamental way. E.g., it's not a balance sheet of bad things and good things, it's that the good thing is in the present *political economy* inextricably bound to the bad thing. You can certainly disagree, but if you want to be heard for what you have to say, I think you want to not just wave that fairly deep-seated perspective off as if it's just obviously an empirical error.

I think if you move away from that specific long-running meta-argument, a lot of humanists are also seriously engaged in trying to think about how the world feels and looks to people at any single moment in time, at any single location. So to say to someone living in relative poverty today--say, a 28-year old man in Cape Flats whose only income is from occasional informal-sector work and who has little sense of any aspirational future--that he is so much better off than a Xhosa subsistence farmer living in the Zuurveld in the 15th Century makes no sense even if it is true within the framework you are laying out.

And yet that is what celebrating this moment as "progress" in some sense has to mean. Right now, it only scans or feels like progress to the people who are best off, say the upper 25% or so the income distribution in many societies, or at a global scale--then what we really mean is that there are more people in terms of raw numbers who are materially well-off and the kind of wealth they have is almost unimaginable by the standards of past centuries. That's all true in the sense that as an upper middle-class professional living in the United States, my income lets me eat, drink, be clothed and have leisure in a way that rivals princes and emperors of eight or nine centuries ago, and there are millions like me across the planet. I have affordances that no human alive could even have dreamed of three centuries ago. But that's an intellectual comparison--what I feel in a day-to-day sense is how I stand in relationship to the world around me, about whether my prospects will continue to improve, about whether my situation is threatened by relative decline overall or specific degradation of services and infrastructure where I live and work. E.g., what informs my state of mind more is if my healthcare provision both feels worse and is by the same kinds of data you're privileging also worse--to say "well, at least I have better healthcare than writers and intellectuals in Augustan England" is true but isn't terribly meaningful. At the other end of the global income distribution, even less so, especially when people are living in structural poverty that is physically proximate to extraordinary wealth--that they have material affordances that a much greater percentage of poor people would have had five or six hundred years ago isn't just intellectually and emotionally irrelevant to them, and it feels a bit farcical to say with a straight face "but this is progress!" in that context. (If by that we mean, "our present progress within our present systems will eventually lift up even their circumstances to a basic level of universal security and comfort" then I think you have to loop back to the critique offered by left intellectuals and activists who have some reason to think this is not so.)

This is an important topic. I'd add a small clarification in that what it appears you are mainly describing is the Marxification of the humanities, AKA the Grievance Studies (see Peter Boghossian et al). I majored in History just before the student bodies started chanting to 'decolonize' things, including the sciences. To focus on "pure" history or philosophy is mostly safe, but the social anthropology and related depts tend to be extremely corrupted. I don't belive the sciences ever got completely overrun, but instead we see that the average western corporate workplace seems to have taken up the Marxification reigns so as to affect the broadest cohort, via HR departments and Longhouse Politics.