What will happen to the Rand?

GUEST POST: Understanding the reasons for past fluctuations might point the way forward

This is a free post from Our Long Walk, my blog about the economic past, present, and future of South Africa. If you enjoy it and want to support more of my writing, please consider a paid subscription to the twice-weekly posts that include my columns, guest essays, interviews and summaries of the latest relevant research.

One of the most common questions my South African clients ask is: What will happen to the Rand? For most South African residents and businesses, wealth is primarily generated and held in ZAR, yet remains significantly influenced by international factors.

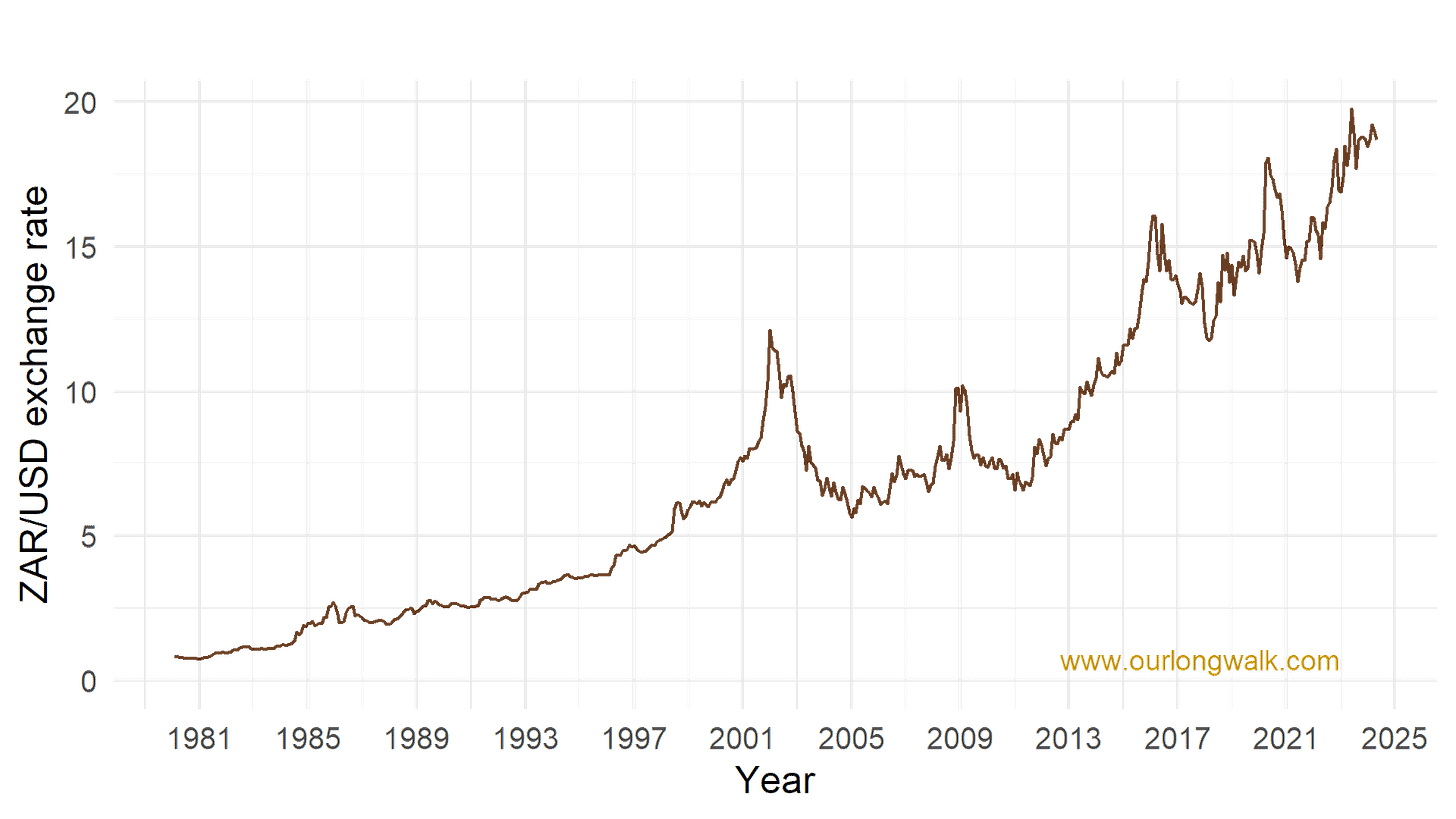

The past few decades have seen a severe devaluation of our local currency, the ZAR (see Figure 1 for USD/ZAR data from 1980 to the present). From 1980 to the string of financial crises around 2001, the ZAR depreciated by a factor of approximately 14, from 0.82 ZAR to 1 USD to 12.12 ZAR to 1 USD. But we have also witnessed, at several junctures, examples of rand recovery and resilience, sometimes entirely unanticipated. From 2001 to the period ending in 2004, the ZAR recovered 53% of its value against the greenback. Similarly, the ZAR experienced an appreciation of 35% between 2009 and early 2011. A stark example is the period following the sacking of finance minister Nhlanhla Nene in December 2015 (along with Des van Rooyen in the same month). Over the ensuing two-year period, the SA economy was plagued by political uncertainty and low growth, state capture allegations and costly credit-rating downgrades. Despite this, the ZAR appreciated by 26% relative to the USD.

By way of introduction, I have been working in finance as well as researching and publishing on financial markets, including on SA assets, asset management, and the ZAR for some time, along with a talented group of colleagues from industry and postgraduate students. Our answers to the question about the future of the Rand may be both unanticipated and unsettling. It consists of four parts.

Firstly, you’d be surprised just how inconsequential local economics and political machinations are to the performance of many local assets, including that of the ZAR. SA might be a miracle in terms of its transition to a peaceful democracy, and it remains one of the most beautiful destinations in the world, yet in terms of its relevance to global capital markets, it remains largely insignificant. The short-term correlations between everyday political events or economic news and the performance of the ZAR are, at best, accidental.

Second, South Africa retains remarkable architecture in terms of its financial exchanges. These, predominantly the JSE1, are world-class in terms of risk management, access, settlement and clearing. This is important in understanding why the ZAR becomes an attractive instrument to foreigners at times. Anything that threatens the capacity and efficacy of trading on these exchanges will remove an important dynamic from our markets. More on this ‘denominator’ later.

Third, the economic theories for the pricing of currencies are both elegant and understandable and include well-known arguments from purchasing power parity, uncovered interest rate parity and the more fundamental balance of payments calculations.2 It is worth noting two things about these theories, specifically the first two. These have largely been debunked, convincingly, as long ago as the 1960s. Regardless, these theories are taught to students, consumed with bright eyes, and then applied with interpretive (often self-fulfilling) vigour to asset and Fx valuations. Also, most of such Fx theories assume cardinality (here, an absolute intrinsic value that a currency should reflect long-term), but in fact, assets are priced from a relative perspective. Assets, including currencies, might not have any intrinsic value in and of themselves and are coupled, in some form or another, to the real economy. Yet, often empirical values of assets stray very far and for long periods of time away from any deemed intrinsic value.

Lastly, capital markets are social systems, and frequently reflexive (dynamic, self-referential and reinforcing). Value is often subordinate to perceptions of value, and despite the dominant, orthodox view of markets possessed by perfect information, rational expectations and a single long-term equilibrium, the empirical reality to traders and investors is often very different.

Global participants and traders are not beholden to economic theories or interested in epistemological paradigms. At best, theories reflect reality over long periods of time, not the other way around. Those traders taking on proprietary risk have a job of creating returns. Over the last few decades, global capital markets have been seen to switch between two regimes: being risk-prone (‘risk-on’) or risk-averse (‘risk-off’), depending predominantly on unfolding geopolitical insecurity and policy uncertainty. Risk-off creates a flight to safe-haven assets – gold and USD for example, or out of emerging markets and into the developed world. Risk-on sentiment results in the deployment of assets into riskier strategies and jurisdictions, including emerging markets. This regime-switching is key to understanding the performance of assets, and the behaviour of the ZAR.

When global risk is on, as it has been for most of 2024 thus far, things become interesting. Borrowing in low-yielding hard currency and investing in high-yielding emerging market currencies (e.g. borrowing Yen and using it to buy SA bond instruments, for example) is termed the ‘carry trade’. It relies on the ability to execute efficiently (and in sufficient size) across global jurisdictions. Attractive carry destinations also require the ability to easily reverse these positions when required (typically in haste). The carry trade has been termed ‘picking up pennies in front of a steamroller’ but despite the description, remains a common and often lucrative risk-adjusted strategy. The trade’s attractiveness is an increasing function of interest rate differentials (the numerator in the carry trade) and is inversely related to the jurisdictional risk and the risk of being stuck on the wrong side of liquidity (the denominator). The carry trade comfortably explains the Rand’s performance for approximately two years post-Nenegate, and it is poised to be back in play despite a backdrop of heightened local political uncertainty in South Africa.

But why would this trade currently be supporting the ZAR given global tensions and lingering inflationary fears? Fears of a deep US recession have mostly subsided. Offshore equity markets have rallied strongly this calendar year. With developed-market inflation almost under control, the expectation is for the FED to cut rates (later in 2024 or early 2025) which will likely precede a cycle of global rate cuts. Local inflationary pressures remain though, and the SARB would likely be slower to act should developed market rates come down (for fear of lingering inflation and capital outflows/currency weakness).

The numerator in the carry trade (on a forward-looking basis) is looking increasingly attractive. In the absence of escalation in geopolitical tensions, or lingering inflation in the USA, assume risk is on. As inflation cools overseas, and the SARB does not cut rates simultaneously, expect the rand to appreciate further on the back of a re-invigorated carry trade. While the recent elections will have tremendous bearing on the lives of all South Africans, it will unlikely impact the ZAR yield pick-up appeal for foreign traders in the medium term. The denominator appears to be priced with the sentiment that ‘nothing changes quickly post 29 May 2024’. With the election outcome now known – local investor jitters are acute. Foreigners are also on high alert and broadly wondering how the spectre of a feared populist kleptocracy differs in substance from that of previous ANC-dominated rule in terms of the safety of their (transient) Rand assets. Would such a doomsday coalition essentially result in a failed state and associated sovereign default, and if so, how rapidly?

When SA rates normalise, which they ultimately will, or events transpire to shift away from the carry trade, other narratives will take hold. And here longer-term fundamentals come to bear. In the absence of economic growth, foreign direct investment, and revitalisation of the South African brand, these do not support a strengthening ZAR.

My point is that the ZAR can and has surprised previously on the upside by appreciating considerably and for a lot longer than expected (see post-2001, 2009 and 2015 examples). The probability of doing so remains primed, which will seem like an odd statement currently to most South African readers.

As we watch an ineffectual liberation party lose majority control, expect the Rand to serve as a punching bag for domestic fears, or as a crutch for democratic gains. It is worth remembering that our currency drivers are predominantly foreign-weighted. And the ZAR may yet offer compelling risk-adjusted yields under the right trading circumstances.

We are in for a fascinating stretch ahead.

‘What will happen to the Rand?’ was first published on Our Long Walk. The images were created with Midjourney v6.

Subsuming BESA and including SAFEX.

Purchasing price parity implies, for example, that a basket of goods (or a Big Mac) should cost more or less the same over time in different geographies. Uncovered interest parity means that interest earned in excess of inflation and depreciation should, over time, be similar in different geographies. Balance of payments argues that trade surpluses should reflect the net demand or supply of currencies – which in turn then drives their values.

Really useful piece, which I wish more people would read. The mainstream business press seems to think the coalition (and SA's future) should be decided on the prospective value of the ZAR alone.