VAT up, doc?

There are no solutions; there are only trade-offs

‘Value Added Tax (VAT) is,’ according to economists Michael Keen and Joel Slemrod in their excellent book Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue, ‘the most remarkable fiscal success story of the last half-century’.1 While early discussions of a VAT-like system emerged in Germany in the 1920s, the first modern VAT was introduced in France in 1954. It gained momentum in the 1960s when the European Economic Community made it a requirement for member states. Today, VAT is levied in more than 170 countries, generating almost 30% of global tax revenue, making it one of the most significant sources of government income worldwide.

Why is VAT so popular? Unlike traditional sales taxes, VAT minimises distortions by taxing value added at each stage of production rather than just at the final sale. This avoids tax cascading, where the same goods or services are taxed multiple times along the supply chain. Another advantage is its border-adjusted nature: exports are zero-rated while imports are taxed as domestic sales. This ensures a neutral impact on trade, preventing countries from using VAT as a hidden protectionist tool while still allowing them to set their own rates. These features make VAT less disruptive to markets and more compatible with economic integration, a key reason for its widespread adoption in the European Union and beyond.

For developing countries, VAT has been a pillar of tax reform. Research shows its adoption often coincides with broader fiscal restructuring, particularly under IMF-supported programmes aimed at stabilising public finances. Unlike income taxes, which can be harder to administer in economies with large informal sectors, VAT is collected at multiple points, making evasion more difficult. Today, about three-quarters of countries with VAT are low- or middle-income economies, and two-thirds of the world’s least developed nations rely on it as a major revenue source.2

VAT has been a cornerstone of South Africa’s tax system since its introduction in 1991, replacing the flawed General Sales Tax. Initially set at 10%, it sparked fierce opposition, culminating in a mass strike on 4 and 5 November, when an estimated 3.5 million COSATU workers protested against what they saw as an unfair burden on the poor. Its leaders argued that VAT’s regressive nature – where lower-income households spend a larger share of their income on taxable goods – made it particularly harmful. In response, the government introduced key zero-rated exemptions, including maize meal and brown bread, to ease the impact on low-income consumers. This has reduced its regressive nature, though research by Calitz & Jansen (2017) and Van Oordt (2018) suggests that, despite its popular appeal, zero-rating remains an inefficient way to support the poor.3 Redistribution is much better done through the expenditure side of the budget.

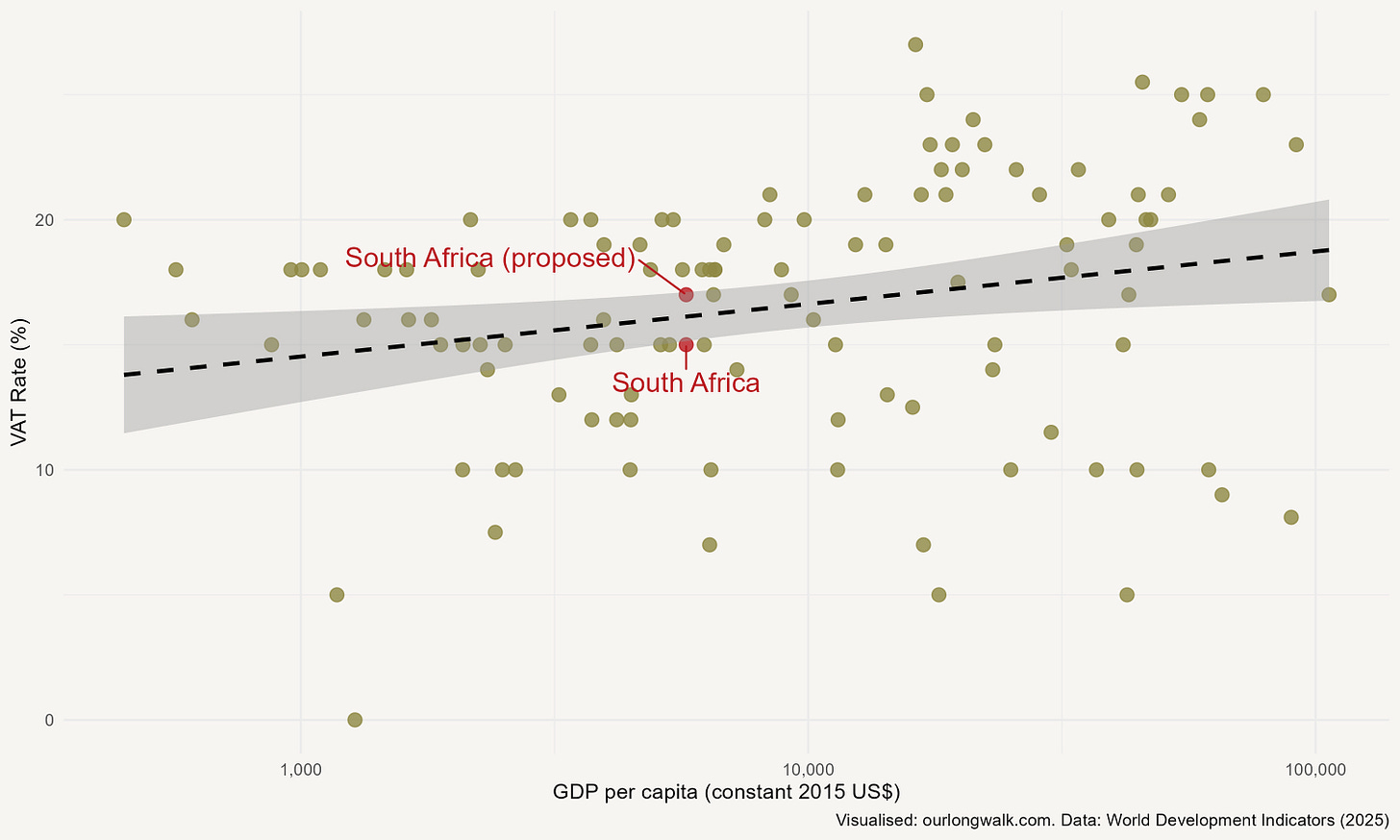

Since its introduction in 1991, VAT has remained a pillar of revenue collection, with its rate increasing only twice – to 14% in 1993 and 15% in 2018. Today, South Africa’s VAT rate is relatively low by international standards. The graph below compares VAT rates across countries with different levels of GDP per capita, showing that South Africa’s current rate aligns closely with global norms for economies at a similar income level. Even with a two-percentage-point increase, it would remain within the expected range.

But a VAT hike to 17% now seems unlikely. That is because, on Wednesday last week, Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana was forced to postpone his Budget Speech after his proposal to raise VAT by two percentage points met immediate resistance. Just hours before the budget, Cabinet members were formally informed of the increase, triggering swift opposition. GNU partners rejected the proposal, while several ANC ministers also pushed back, citing either the short notice or concerns over its impact.

With no consensus, Godongwana delayed the budget until 12 March, an unprecedented move. But the fundamental question remains: if VAT is off the table, where will the government find the revenue to close its budget gap?

The political drama of the past week has made one thing clear: budgetary trade-offs can no longer be postponed. The Minister himself admitted as much: any final decision on taxes or spending will require all parties, both in government and opposition, to confront the hard choices head-on.

One popular response has been to blame corruption and wasteful spending, arguing that the missing R60 billion can simply be recovered by eliminating graft, cutting ministerial perks, or scrapping blue-light brigades. But this is wishful thinking. Not only is corruption not a budgeted line item, but even if every instance of waste were magically erased overnight, it wouldn not come close to filling the fiscal hole.

A more serious argument favours spending cuts, but deep reductions in a single budget cycle are unrealistic. The public sector wage bill is locked into multi-year agreements, interest payments are legally unavoidable, and social grants, after the court ruling on Covid relief, are now effectively untouchable. As Michael Sachs has put it, cutting everything else leads only to ‘austerity without consolidation’ – hollowing out education, infrastructure and public services without fixing the underlying problem. With debt rising and growth stagnating, the usual escape routes are gone.

Political wrangling further complicates matters. Although the Minister in the Presidency insists this should not be seen as a party-political standoff, it’s clear there is resistance within the ANC and its alliance partners, who have traditionally opposed a VAT hike. Relations are also strained with SARS after its commissioner suggested that further tax increases would yield little additional income. This suggestion prompted a sharp response from the Finance Minister, who reminded SARS to focus on administration rather than policy.

Despite the rare unity across the political spectrum in rebelling against the Budget Speech, there’s been little clarity on a viable alternative. As Thomas Sowell put it, ‘There are no solutions; there are only trade-offs’. South Africa urgently needs long-term fiscal planning, aligning with global best practices rather than relying on last-minute political brinkmanship. In the short term, VAT – despite its flaws – remains one of the least distortionary ways to raise revenue. It is not ideal, but the alternatives – cutting spending on education, healthcare or infrastructure, or taking on more debt – come with a high risk of being worse.

An edited version of this post appeared (in Afrikaans) in Rapport on 23 February 2025. Kelsey Lemon, Lisa-Cheree Martin and Nape Motswaledi provided helpful research assistance. The images were created using Midjourney v6.

Keen, M. and J. Slemrod, 2021. Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue: Tax follies and wisdom through the ages. Princeton University Press.

James, K. 2015. The Rise of the Value-Added Tax. Cambridge University Press.

Calitz, E. & Jansen, A., 2017. Considering the efficacy of value-added tax zero-rating as pro-poor policy: The case of South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 34(1), pp.56–73; Van Oordt, M., 2018. The efficiency of value-added tax in South Africa: A ratio analysis. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 21(1), pp.1–11.

Thank you for the very technical description of VAT. Value-added tax is still the best tax as it is a consumption tax. The more you consume, the more you pay, and it does not ask you for anything such as a certificate, tax, or ID number, or anything related to your status in life.

In my view, the zero rating of the foodstuff is just a popular trade-off without any real value. Let us take 2% and give you some insignificant trade off.

It just creates more compliance costs and the legislative part thereof is always very difficult to draft, enforce and comply with. Suppliers need lots of rules and such, the cost to comply ends up in the cost of the product. Just another issue for SARS to pick on.

If all the taxes we pay were collected correctly, the government should in theory be able to apply it to the grants or department where it is needed. My concern is that it is collected and then mismanaged.

Why are we looking backward to fix future income, but not looking backward and asking why we are here?

I am not supporting the VAT increase, as it does not come with a guarantee that we will have the same arguments a year later. Last year, we took gold reserves, it seems at budget time "let's pick the low hanging fruit" to fill the gap without any forward thinking. Kick the can down the road.

For example, if we make the retirement age of government employees, let's say 65, the majority of the persons currently in control would have made "space" for the 55 year olds with hopefully a rejuvenated thinking process.

When are we going to run South Africa as a business?

Should not Substack itself be charging VAT in South Africa?