Time to tell Africa's stories

A centre, a chair and a conference

Storytelling is a fundamental part of human civilisation. They shape not only our identity and societal norms but also influence our economic decision-making and outcomes.

That is why the Economics Nobel laureate Robert Shiller promotes the study of ‘economic narratives’, positing that stories and their propagation can affect significant economic events like the Great Recession.1 These narratives, appearing in various formats, from news articles to jokes, provide simplified explanations that cater to our biases and beliefs rather than detailing all facts. Barry Eichengreen, an economic historian at Berkeley, supports this view by noting how policymakers use analogical reasoning rather than deductive (theory) or inductive (empirics) reasoning during crises, drawing from history to shape responses and public perception.2

For that reason, expanding policymakers’ historical analogies is essential, argues Niall Ferguson. In a recent article in the Journal of Applied History, Ferguson notes that ‘the case for applied history is an unpretentious one. If history is, as former Defense Secretary Ash Carter once remarked, “the language that is spoken” in the corridors of power – not economics, not political science – then it is surely desirable for those who inhabit those corridors to speak it fluently: in other words, to be aware of the pitfalls as well as the power of arguing on the basis of historical analogies.’3 To help policymakers choose the most appropriate historical examples, Eichengreen encourages a more in-depth study of economic history.

I would argue this is even more true in developing countries, where economic history, and in particular the effects of past policies, are poorly understood. For example, apart from, say, Roy Havemann’s excellent dissertation on small bank failures in South Africa between 2002 and 2014, there is almost no recent academic work on bank crises in South Africa’s past. Were banks to fail, it is unclear which historical analogies policymakers will use.

That is why economic history matters – why it is an important research field and why it should be part of any economics curriculum.

We have done so for over a decade at Stellenbosch; in fact, our roots go much deeper, to the economic histories produced by scholars like Jan Sadie and the legendary Sampie Terreblanche (with his entire archive available here). But over the last decade, encouraged by the renaissance in African economic history, we have used new sources and the latest methods to uncover new insights into South Africa’s economic past, from eighteenth-century settler wealth4 to twentieth-century inequality5, from slavery6 to prosperity7, from voters8 to taxes9 to land10 to firms11 to health12. And we have developed a course for undergraduates that introduces them to the latest global economic history research from a South African perspective, now turned into a commercial book Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom (and Skatryk, in Afrikaans).

But more can be done to strengthen our research and teaching and, importantly, disseminate our work to a larger audience. In short, the stories economic historians tell must have an impact.

That is why I am happy to announce two initiatives at Stellenbosch.

First, LEAP, the Laboratory for the Economics of Africa’s Past, has become a formal Type-1 centre of Stellenbosch University. I am its first director. The formalisation will give us more transparency and guidance; our first board meeting already showed the value of expert advice. Hopefully, it will also allow us to attract more research funding and bursaries.

Second, inspired by the Centre for Economics, Policy and History, a joint initiative of Trinity College Dublin and Queen’s University Belfast, I will also head a new Chair in Economics, History and Policy within LEAP. The Chair is generously sponsored by The Millennium Trust. It will allow us to appoint postdocs and work on fun and exciting projects to share the results of our research with new audiences. I will share more information about some of these initiatives in the following months.

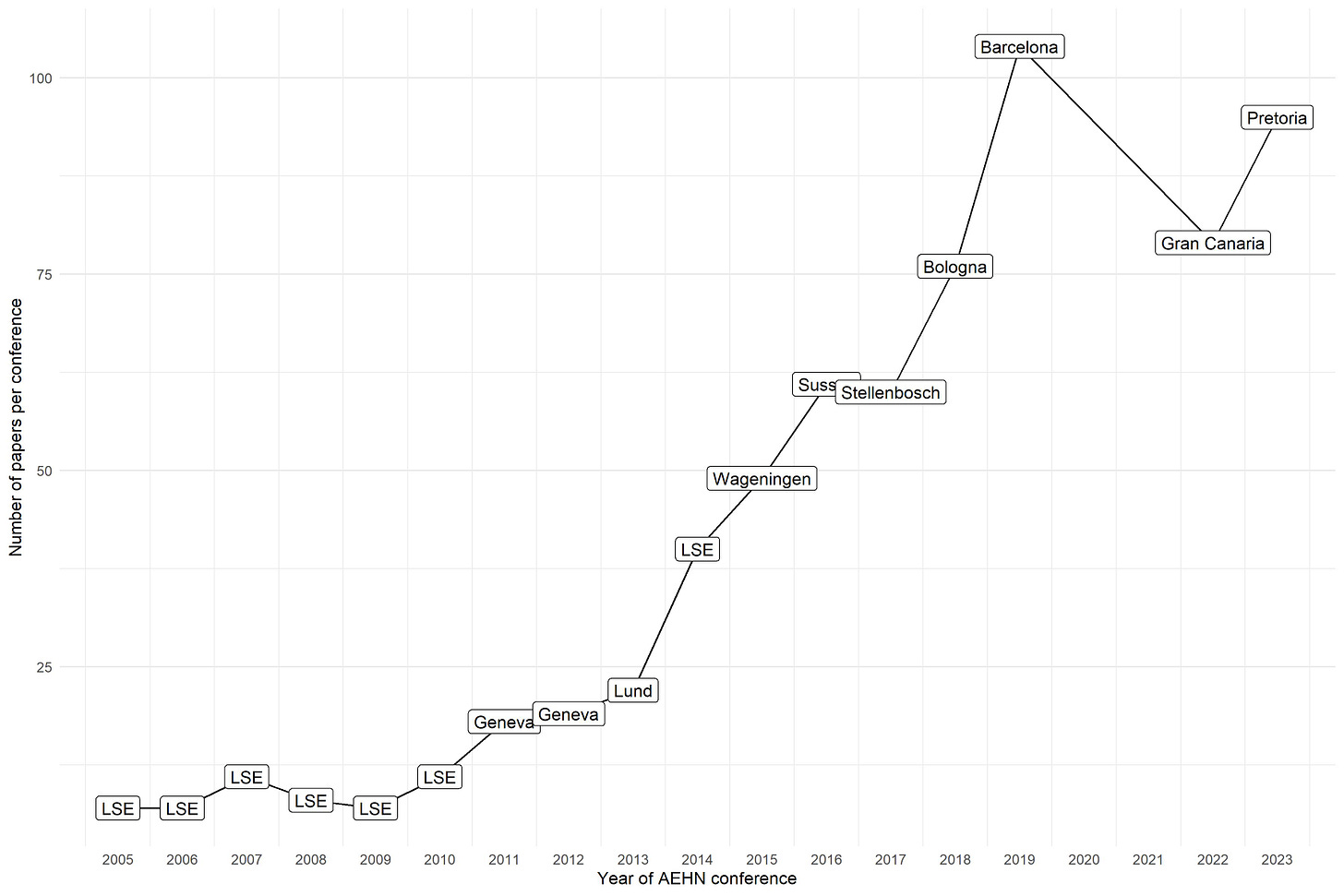

It is not only at Stellenbosch where the economic history action is happening. This week, the African Economic History Network meets at the University of Pretoria. Hosted by Carolyn Chisadza (Economics, Pretoria), Tinashe Nyamunde (History), and Christie Swanepoel (Economics, UWC), the annual meetings bring together more than 90 African economic historians from across the world. As the figure below illustrates, it will be the second-largest meeting of its kind.

The figure also shows the growth in African economic history over the last two decades. As I have written about before (in 2013, in 2014, in 2019, and Leigh Gardner on this blog in 2023) and will do again in an upcoming chapter, one usual concern is the lack of African participation in African economic history. However, hosting the event in Pretoria makes a difference: from the conference programme, it is clear that many more local scholars and students are attending.

As I’m on paternity leave, I, sadly, will miss out this year. But there are many great papers on the programme, with LEAP well represented. Colleagues Calumet Links, Dieter von Fintel and Ed Kerby are presenting, as are postdocs Leoné Walters and Jonathan Schoots, Master’s student Kereeditse Tsokodibane, and former students Jeanne Cilliers, Lloyd Maphosa and Lauren Coetzee. Several LEAP research associates will also attend.

Africa is not on the periphery of economic history research any longer. But we must make sure these discoveries really make a difference. I cannot wait to focus on telling Africa’s economic history stories in new and creative ways over the coming years.

Shiller, Robert J. "Narrative economics." American Economic Review 107, no. 4 (2017): 967-1004.

Eichengreen, Barry. "Economic history and economic policy." The Journal of Economic History 72, no. 2 (2012): 289-307.

Ferguson, Niall. "Applying history in real time: A tale of two crises." Journal of Applied History 5, no. 1 (2022): 1-18.

Fourie, Johan, and Frank Garmon Jr. "The settlers’ fortunes: Comparing tax censuses in the Cape Colony and early American republic." The Economic History Review 76, no. 2 (2023): 525-550.

Von Fintel, Dieter, and Johan Fourie. "The great divergence in South Africa: Population and wealth dynamics over two centuries." Journal of Comparative Economics 47, no. 4 (2019): 759-773.

Ekama, Kate, Johan Fourie, Hans Heese, and Lisa-Cheree Martin. "When cape slavery ended: introducing a new slave emancipation dataset." Explorations in Economic History 81 (2021): 101390.

Mpeta, Bokang, Johan Fourie, and Kris Inwood. "Black living standards in South Africa before democracy: New evidence from height." South African Journal of Science 114, no. 1-2 (2018): 1-8.

Nyika, Farai, and Johan Fourie. "Black disenfranchisement in the Cape Colony, c. 1887–1909: Challenging the numbers." Journal of Southern African Studies 46, no. 3 (2020): 455-469.

Gwaindepi, Abel, and Krige Siebrits. "‘Hit your man where you can’: Taxation strategies in the face of resistance at the British Cape Colony, c. 1820 to 1910." Economic History of Developing Regions 35, no. 3 (2020): 171-194.

Chingozha, Tawanda, and Dieter von Fintel. "The complementarity between property rights and market access for crop cultivation in Southern Rhodesia: evidence from historical satellite data." Economic History of Developing Regions 34, no. 2 (2019): 132-155.

Maphosa, Lloyd Melusi, Anton Ehlers, Johan Fourie, and Edward M. Kerby. "The growth and diversity of the Cape private capital market, 1892–1902." Economic History of Developing Regions 36, no. 2 (2021): 149-174.

Fourie, Johan, and Jonathan Jayes. "Health inequality and the 1918 influenza in South Africa." World Development 141 (2021): 105407.

I have to say that Ferguson is not a particularly good guide to the honest use of historical analogies, overall.

But I am fond of the position you craft here, which is that the use of African histories in analogies would be one useful strategy for "provincializing the West", and it's up to experts in African history to play a role in incubating those analogies, essentially trying to seed popular and policy-making conversations with analogies from African history that do not relentlessly use African societies and individuals as either the non-comparable other or as a figment of the Western imperial imagination. When someone talks about issues with dynastic politics in large imperial states, for once have them mention the succession issues in the early history of Mali rather than the history of Julio-Claudian Roman emperors. When someone talks about cosmopolitan trading communities and trading diasporas, have the Swahili towns of East Africa be the point of reference.

The 1948 election in South Africa is a fantastic analogy for the problems of many liberal democracies right now, that is, the consequences of voting systems that artificially weight rural populations and aggrieved reactionary populisms slightly more heavily and allow a minoritarian party to win a general election, after which that party uses its control of government to lock in an electoral advantage, persecute its electoral opposition, and create a permanent emergency that keeps it in power in perpetuity while still technically being 'democratic' on paper. People should be talking less about late Weimar and more about 1948.

I think part of the trick is precisely that good analogies require skill at storytelling--it's not the same as finding a good but formalized comparative framework in the style of political science or economics. (Skill at storytelling in turn is what makes some people wary of analogies, in that it's possible to insidiously distort the subject of the story to fit the requirements of the analogy.)

Congratulations on your new positions..