The unequal parental penalty

What the Constitutional Court ruling on maternity leave teaches us about fairness

A month or so before my son was born, I was having coffee with two female colleagues. I remember one part of the conversation vividly. When they asked about my wife’s pregnancy, I said I wasn’t sure how it would affect my productivity after the birth. ‘Less research’, I imagined. They looked at each other in disbelief. I’m paraphrasing, but their response was something like, ‘You’ll have plenty of time. There’s a very good chance you’ll actually do more research.’ I smiled but thought it was a rather discriminatory remark. Why shouldn’t I have equal time with my son? The thing is, they were right.

That conversation came back to me when I read the recent Constitutional Court ruling in Van Wyk and Others v Minister of Employment and Labour. The Court found that South Africa’s maternity and parental-leave provisions unfairly discriminated between mothers and fathers. It replaced gender-specific leave with a shared model: if both parents are employed, they are now jointly entitled to four months and ten days of parental leave, which they can divide however they wish.

Formally, it is a victory for equality. Fathers gain legal recognition as caregivers, and mothers are no longer assumed to shoulder all early childcare. The new law embodies the spirit of the Constitution, which guarantees equal rights regardless of sex or family status. Yet equality before the law is not the same as equality of outcomes. The Court’s ruling does not increase total family leave; it simply redistributes the same four-month period. Economically, this creates a trade-off. By sharing a fixed quantum of leave, the reform may make women worse off in practice even as it looks fair on paper.

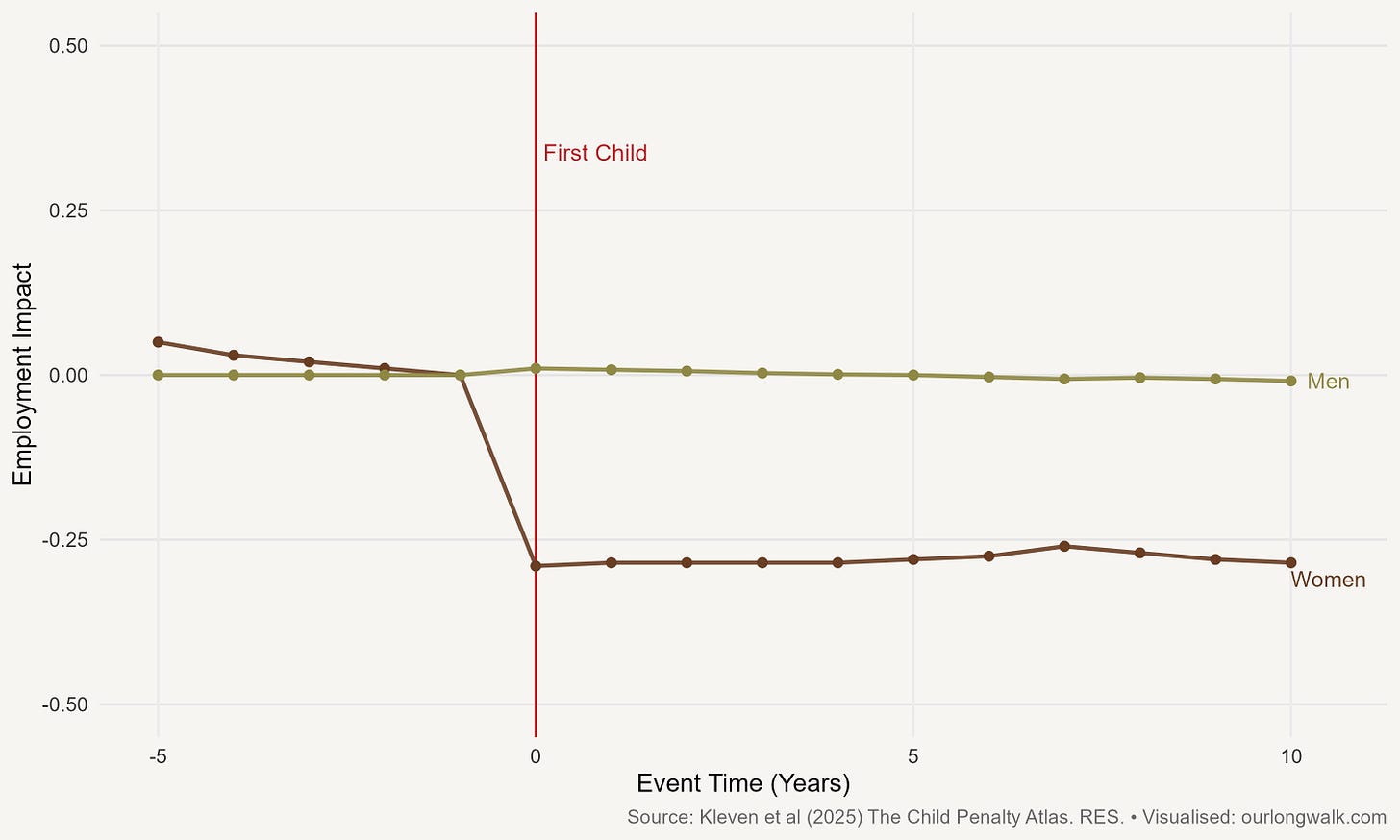

Economists have a term for this kind of unintended outcome: the child penalty. It refers to the decline in women’s earnings and employment relative to men’s after the birth of their first child. A new global study by Henrik Kleven and co-authors, The Child Penalty Atlas (2025), maps this phenomenon across 134 countries. The results show that in almost every country, men and women follow parallel career paths until parenthood, then diverge sharply and permanently once children arrive. And South Africa stands out: our child penalty, as the figure shows, is around 28 percent, among the highest in Africa and globally. That means that, relative to men, South African women’s employment falls by roughly a quarter after having a child, and it never fully recovers.

This penalty captures more than just lost wages. It reflects how norms, childcare costs and workplace expectations combine to make motherhood the decisive fault line in gender inequality. The irony is that as economies develop and more people move into formal, salaried work, the penalty tends to grow. Subsistence farmers can care for infants while working; accountants cannot. Development creates prosperity but also sharper trade-offs between work and care.

The Constitutional Court’s ruling aims to address one part of that trade-off: the unequal legal treatment of mothers and fathers. But whether it reduces South Africa’s child penalty depends entirely on behaviour, and specifically on who actually takes the leave.

In a radio interview discussing the amendment, Wessel van den Berg said that the law’s use of the ‘shared model’ of parental leave ‘misses the boat’.1 Van den Berg, who works at Equimundo, a gender-equality advocacy group, argues that by forcing parents to share the four months and ten days of leave, the ruling necessarily reduces women’s maternity leave overall. Additionally, in a country with such high rates of split-parent families, not to mention abusive partnerships, the decision around how parental leave time is divided might become impractical, if not contentious. In contexts of abuse, such a decision could be weaponised against pregnant women. This, Nthabi Nhlapo noted on News24, could force many women to negotiate with uncooperative or hostile partners.

South Africa is not the only country with a shared parental-leave policy. Since 2015, parents in the UK receive up to 50 weeks of shared leave during their child’s first year. Writing in 2023, University of York professor Patricia Hamilton called the programme a ‘failure’.2 The year it was introduced, only one in 100 men requested parental leave.3 Research from elsewhere shows the same pattern. In Poland, which has one of the most generous schemes in the world, offering 32 weeks of shared leave plus 20 weeks of exclusive maternity leave at 80 percent income replacement, just 1 percent of fathers take any parental leave at all.4

Sweden pioneered paternity leave in 1974, yet only 6 percent of eligible men took it each year until the government created a “daddy quota” in 1995: non-transferable, use-it-or-lose-it leave for fathers. Similar policies in Iceland, Norway, South Korea and Japan have massively increased men’s use of parental leave.5 Even so, these reforms have not closed the baby-penalty gap. Research by Andresen and Nix helps explain why.6 Studying Norway, they find that women typically take leave immediately after birth, when formal childcare is unavailable and mothers are recovering physically. ‘Fathers’, on the other hand, ‘much more frequently take leave at ‘convenient times’ such as holidays when mothers are likely around, or when their child is in formal care’, they write. ‘This ‘convenient leave’ presumably makes it easier for fathers to continue their careers’, since disruptions can be planned in advance, ‘allowing fathers and firms to jointly minimise career interruptions.’

Fathers who take leave in ways similar to mothers, early and intensive, face a ten-percentage-point smaller child penalty. Andresen and Nix conclude that ‘governments interested in introducing paternity leave to reduce gender income gaps by encouraging fathers to (sometimes) be primary caregivers may wish to put more stringent requirements on paternity leave’. Notably, South Africa’s amended policy requires parents to take their shared leave within four months of the child’s birth, adoption or surrogacy order. That may prevent the kind of flexible, later-in-the-year leave fathers tend to prefer, but it does not compel them to take any leave at all.

The international lessons are clear. Gender-neutral leave without non-transferable quotas for fathers rarely changes behaviour. When leave can be freely divided, couples typically allocate it to whoever earns less, usually the mother. The result is that the woman still takes most of the time off, reinforcing gender norms that position women as primary caregivers, while men keep working uninterrupted. Yet under South Africa’s new arrangement, any time the father does take now comes out of the mother’s previous allotment. If both take two months, the mother loses half the recovery period she once had. That might sound like progress towards equality, but it could also mean shorter breastfeeding, poorer maternal health and less job protection.

Laws that look symmetrical often have asymmetrical effects. As Nthabi Nhlapo reminds us, men’s and women’s bodies, social expectations and career paths are not mirror images. Alison Davis-Blake, a lecturer at the University of Michigan, put it more sharply: ‘Giving birth is not a gender-neutral event.’7 The hope that shared parental leave will close the child-penalty gap rests on a heroic assumption – that men will behave differently once they have the right to. Experience elsewhere gives little reason for optimism. Economics helps explain why. Lawyers focus on formal fairness, equal treatment and consistent rules; economists study substantive fairness, the outcomes that emerge once people respond to incentives. Formally, the new policy is fair. Substantively, it risks reinforcing inequality by reducing women’s leave while leaving men’s behaviour largely unchanged. Equality of rights does not ensure equality of results.

If genuine gender equality is the goal, the evidence points to non-transferable leave for each parent, adequate pay during leave and accessible childcare. The Constitutional Court’s decision reveals a deeper paradox of fairness: laws that seem egalitarian can produce unfair outcomes when they overlook differences in biology, incentives and norms. Mothers may lose time for recovery and bonding, fathers may not take on much more responsibility, and South Africa’s 28 percent child penalty will likely persist. I think back to that conversation before my son was born. My colleagues were right: my productivity rose, my wife’s did not. Even with shared ideals and supportive employers, the burdens were not equal. That is what economists call a child penalty, and what the law still struggles to see clearly.

This is an edited and translated version of my monthly column, Agterstories, on Litnet. To support more writing like this, consider becoming a paid member. The image was created using Midjourney v7.

Celeste Martin, “Advocacy group warns ConCourt ruling on shared parental leave misses the mark.” Eye Witness News, 6 October 2025. https://www.ewn.co.za/2025/10/06/advocacy-group-warns-concourt-ruling-on-shared-parental-leave-misses-the-mark

Patricia Hamilton, “Shared parental leave has failed because it doesn’t make financial or emotional sense.” The Conversation, 21 August 2023. https://theconversation.com/shared-parental-leave-has-failed-because-it-doesnt-make-financial-or-emotional-sense-206152

Caroline Criado Perez (2019) Invisible Women: Exposing data bias in a world designed for men. Penguin Vintage: London, 85.

Nikki van der Gaag, Taveeshi Gupta, Brian Heilman, Gary Barker and Wessel van den Berg, (2023) State of the World’s Fathers 2023: Centering care in a world in crisis. Washington, DC: Equimundo. https://www.mencare.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/State-of-the-Worlds-Fathers-2023.pdf

Caroline Criado Perez (2019) Invisible Women: Exposing data bias in a world designed for men. Penguin Vintage: London, 84–5.

Martin Eckhoff Andresen and Emily Nix, (2025) “You can’t force me into caregiving: Paternity leave and the child penalty.” The Economic Journal, ueaf057.

Justin Wolfers, “A family-friendly policy that’s friendliest to male professors.” New York Times, 24 June 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/26/business/tenure-extension-policies-that-put-women-at-a-disadvantage.html

Great analysis, Johan. I really like reading this and thinking about the perspectives.

With a 2-year old, a relate close to what you've written. I'm one of those fathers that would've benefited greatly from this ruling. I saved as much leave as I could, we had a new leave benefit introduced at work, used that dismal amount of parental leave, and got to take off a full month. I like to think that I've been very involved (I'm someone with a strong sense of responsibility). Of course, there are things only moms can do. The reason I would've been able to take the 4 months, is that my wife resigned her job anyway, so it would've been of no benefit to her (except for claiming UIF). Now, I realise that this is one of the core arguments of the article: Women has it worse when it comes to their careers, income and financial independence (I agree). Regardless, it was her choice to resign, because she wanted to spend as much time as possible with our daughter during the initial years, and financially I was happy to support the decision, now being relied on as the sole earner in the family.

What really sucks about parental leave with the existing 10-day allocation, is that only 5 days are paid. It's just that you must be allowed to take 10 consecutive days, so you need to top it up with normal leave, or take it as unpaid leave, because you're also not allowed to use family responsibility leave.

And I would say this is certainly a minority win (for same-sex parents, adoption and surrogacy).

Interesting article. Is your argument that the child penalty should be spread across both parents instead of the mother? Given as you say child birth is not gender neutral is this even possible? And also why would we want both parents after having a child to have lower income instead of just one parent?