The thin pipeline

Why are there so few South Africans doing a PhD in Economics in the US?

In a recent post, I asked whether South Africa’s economists mattered. I made the point that most of the best economics research produced about South Africa is not produced in South Africa or by South Africans. The reaction – via email and in WhatsApp messages – made it clear that I was not alone in my thinking, though I suspect a silent counterfactual cohort preferred not to reveal their priors in the comments section.

So let me make an even more provocative (and unsupported) statement: South African economists are, for a variety of reasons, largely isolated from the frontier of economics research. I made the point previously that there are very few of us publishing in top economics journals. There are also very few of us sitting on the editorial boards of top journals. There are very few of us presenting at the top economics conferences, being invited to give keynotes or spend sabbaticals, or heading up large, collaborative research projects.

There can be many reasons for this. Perhaps this is still a remnant of apartheid-era isolation. But it has now been more than three decades and, though I have no proof of this, it did feel as if South African economists had a seat at the table in the late 2000s, when Harvard would send a team of experts here, many of whom collaborated with local scholars, and several universities were sending students abroad. Since then, largely reflecting the fortunes of the economy, South African economists have lost their international foothold. Perhaps the juniorisation of the profession is one reason, itself the consequence of many things. Or the relative decline of academic salaries, meaning that the best and brightest find alternative employ. (A revealing data point on intrinsic motivation: I’m still in the sample.) And, as my colleagues would know, I abhor the increasing administrative requirements that leave little time for research-related things. Those are all issues that warrant attention, but my focus will be on another – and perhaps the most important – concern: the thin pipeline.

But first: why should we worry about where South Africa’s economists are trained? I want to propose that the isolation of South Africa’s economists matters for two reasons: first, our policymakers and policy commentators do not have access to the top experts, and, second, neither do our students. It should be self-evident that we want researchers using the most up-to-date ideas to inform our policy process. But top research is not just the outcome of intellect but also of networks. In short: being trained by the best is much more likely to also make you the best. Why not just hire non-South Africans. That’s one option, but I would argue that a South African is much more likely to understand the country’s history, cultures and communities in ways that are hard to teach. So a South African with a US PhD won’t just have technical skills, but the ability to ask the right questions, and design policies that are both rigorous and rooted in local reality.

To be fair, there are several ongoing initiatives aimed at strengthening our international collaboration. I think it is important to acknowledge that ESSA – the Economic Society of South Africa – is more pro-active than it has been for many years. ERSA – Economic Research Southern Africa – is also actively organising various policy-related conferences around the country. There are research groups, like SALDRU, whose December conference is aimed at attracting some of the top researchers working on South Africa from abroad to present their papers to a South African audience. At Stellenbosch, we’ve built strong collaborations with international scholars at several leading universities; James Robinson, for example, was awarded an honorary doctorate a few months before he was awarded the Nobel prize in economics.

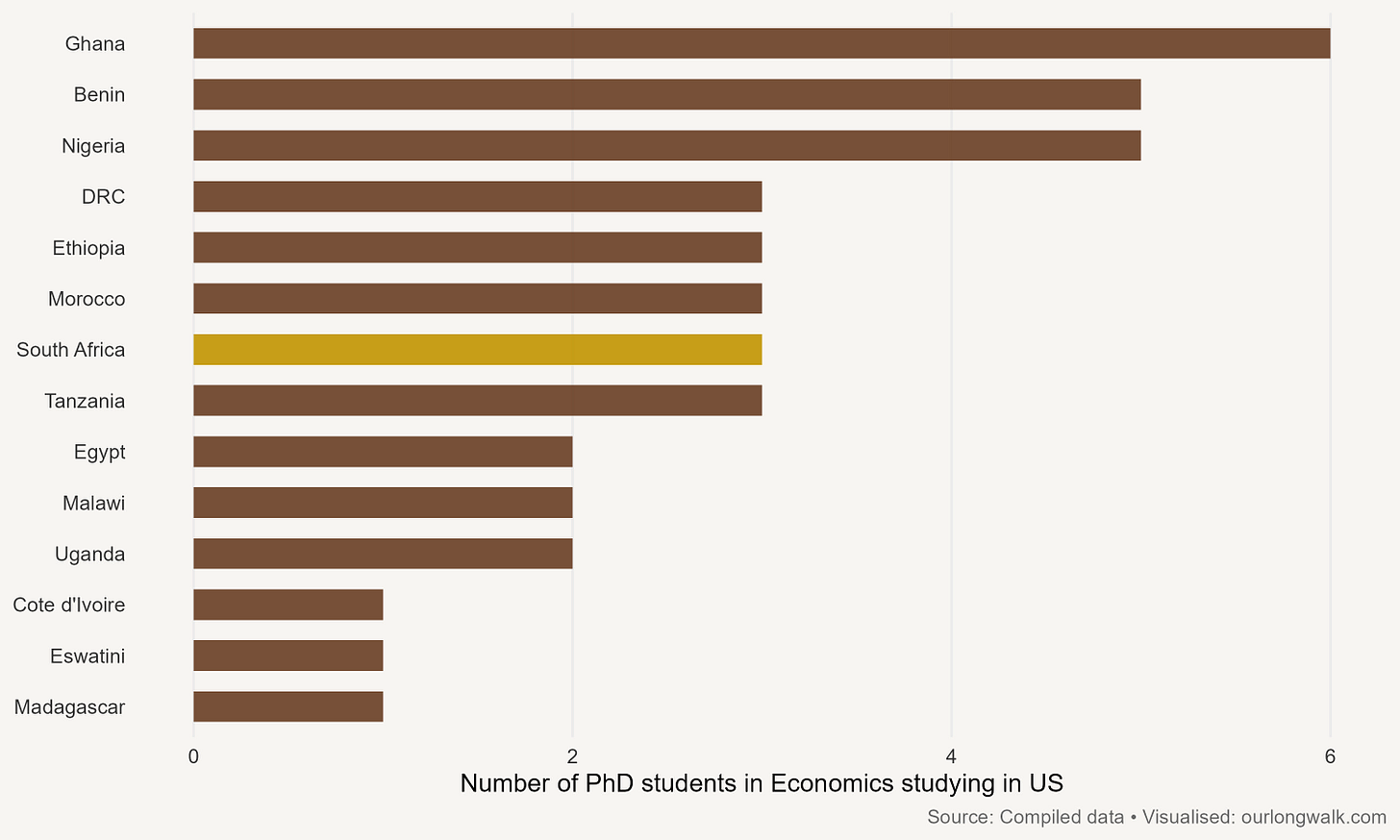

But none of those address the elephant in the room: there are just too few South Africans studying at the best economics departments in the world. Here I do have evidence. I asked a team of RAs to scour the top fifty US economics departments for South African and African students.1 We counted 42 students from Africa in the top 50 US economics departments. Harvard, MIT, Berkeley, Princeton and Stanford each have one PhD economics student from Africa. Yale has three. The University of Michigan is a clear outlier, with eleven African students. No other university has more than two.

The figure above shows the number of African PhD students studying economics at the top 50 US universities. How many South Africans in total? Three.2

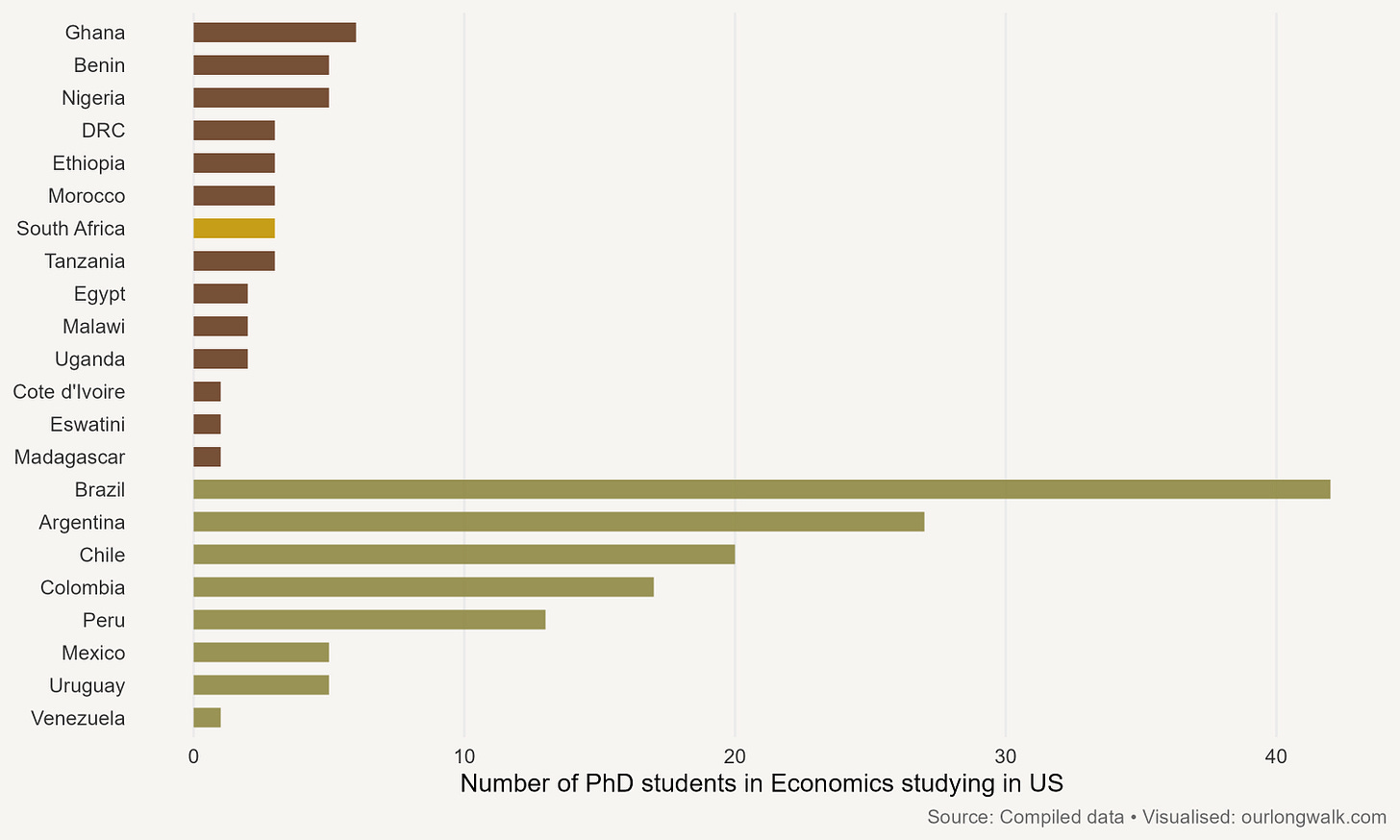

There are many ways I can compare this, but let me just provide a single statistic as comparison. In total, Brazil has 47 students doing PhDs in the US, more than the entire Africa combined. In 2024, the Sao Paulo School for Economics, a single Brazilian university in a single year, sent eleven students to do PhDs in Canada, the UK and the United States. Those universities include MIT, Stanford, Berkeley, Northwestern, and NYU. South Africa has no student studying at an Ivy League institution.3

While I’m at it, let me add another number: In total, there are 137 students from Latin America doing economics PhDs at the top 50 US schools, more than three times the total number from Africa. Keep in mind that Africa has more than double the population size of Latin America. The graph below shows the big gap between African countries and Latin America.

Why are there so few South Africans?