The ruinous growth of sports betting in South Africa

And what to do about it

I’m happy to bet you’re not going to believe the staggering amount that South Africans now spend on sports betting.

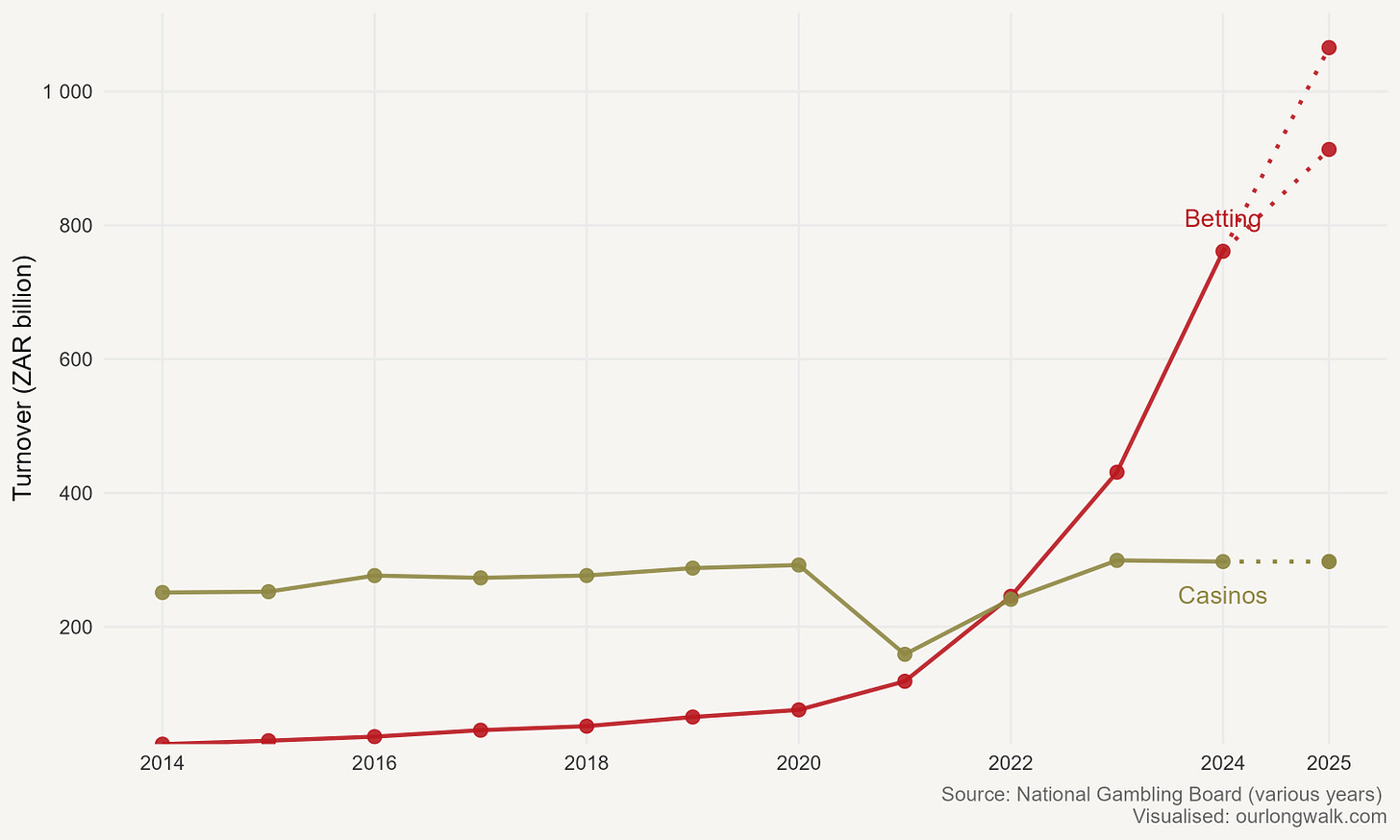

Take a long, hard look at the figure below. In green, you’ll see the turnover of casinos in South Africa, year by year. In red, you’ll see the turnover from betting – almost all of it sports betting – tracked over the same period. Just. Look. At. That. Explosive. Growth.

Now let your eyes drift to the y-axis. Yes, you are reading that correctly. In 2025, South Africans spent close to – if not more than – R1 trillion on sports betting.1 To put it into perspective, the total annual income of South African households in 2023 was R4.3 trillion. It should be noted, though, that sports betting turnover includes ‘recycled’ spending, i.e. when winnings are used for another bet. Still, sports betting is now a considerable share of household disposable income.

Two years ago, I explained why this is a deeply worrying trend. What’s most striking is how little public outcry there has been about South Africans spending such a colossal share of their monthly budget on an activity with so few tangible benefits. Research from Uganda pointed out that for the unbanked, sports betting often serves as a desperate, last-resort saving mechanism. New evidence from South Africa only strengthens this concern: one recent survey found that almost half of sports bettors are gambling to cover rising costs, such as school fees and rent, with 70% stating they bet to supplement their income rather than for entertainment.

If anything, the dangers are growing. Sports betting companies are expanding aggressively across emerging markets, particularly in Africa and Latin America, securing sponsorships in local football leagues at a pace that regulators struggle to match. As Koshiek Karan and others have noted, these companies are making a land grab, embedding themselves in the very heart of sport and culture, often before meaningful oversight can catch up. With each passing season, the industry’s reach deepens, and the stakes for society get higher.

What I did not do two years ago – and what is now urgently needed – is to ask what can be done. The costs of inaction are mounting, and the social risks are becoming impossible to ignore.

But why assume this is an issue that needs attention? Are people not simply responding to incentives and signalling their preferences with their behaviour, just like we would expect in a free market?

Here’s why it matters. Every rand spent on sports betting is a rand not spent elsewhere in the real economy. Had these vast sums been allocated to food, education, healthcare, transportation, or even other forms of entertainment, they would have fueled demand, created jobs, and multiplied across the economy. Economists refer to this as the multiplier effect: money spent on groceries supports farmers, shop assistants, and logistics workers, who then spend their wages in turn. Money spent on school fees keeps teachers and administrators employed. Even a basic household repair creates work for tradesmen, manufacturers and retailers.

But when it comes to sports betting, most of that money disappears into a black hole. The lion’s share ends up as profits for a handful of betting companies – profits so vast that, last year, the gross revenue of sports betting in South Africa was larger than the total turnover of Capitec, the country’s biggest retail bank, which now banks more than 20 million South Africans and employs thousands across the country. Sports betting companies, by contrast, operate with far fewer staff and far less positive spillover. Their biggest outlays are on marketing and sponsorship, including buying naming rights for everything from the local T20 cricket tournament to the Springboks, splashing their logos across stadiums and screens, and recruiting iconic sports stars to endorse their products. In truth, sport and marketing are probably the only real beneficiaries of this surge, so expect them to also be the most likely to resist any change. Indeed, many sports organisations claim they cannot survive without these lucrative sponsorships – a common refrain whenever questions of regulation arise. It is an uncomfortable truth: some sporting properties have grown financially dependent on the betting industry, making reform all the more challenging.

We wonder why our economy is not growing, why, in 2024, after almost a year without loadshedding, there was no economic growth compared to the previous year, when the power was off a third of the time. My answer: A massive share of our disposable income is now being siphoned into frivolous sports bets.

And then, of course, come the social costs: the broken families, the anxiety and depression, the missed rent, the children who go hungry. But the hidden costs may be even greater: sports betting devours not only savings, but also time and focus. It distracts parents from their children, from employees on their jobs, and fills every quiet moment with the urge to check a score or place another bet. Like any powerful drug, it takes over the mind. Evidence? Consider the list of the top five most Googled search terms in South Africa over the last year: three of the top five are for sports betting. We have, in effect, normalised carrying the most potent addiction of all in our pockets, twenty-four hours a day, with no stigma and no warning. It really is terrible.

So, what to do about it?

Some answers come straight from an economics textbook. We could make betting less attractive by taxing it more heavily, just as we have done for all things with large negative externalities, like sugar or plastic. The government could also follow the playbook used against tobacco and alcohol: ban or tightly limit advertising, end the sponsorship of teams and tournaments, and force betting companies to display clear warnings about the risks. We can insist on strict identity checks and limits on how much anyone can bet or lose in a given month. Banks and mobile networks could be required to make it easy for customers to block gambling transactions or to self-exclude entirely. In practice, making it even slightly harder or slower to place a bet, by adding in small delays or extra confirmation screens, might be enough to nudge many people out of their worst habits.

We can also do much more to steer people towards better choices. Financial literacy campaigns could be rolled out in schools and workplaces, teaching that gambling is not a way to make money, but a sure way to lose it. Better alternatives could be created – prize-linked savings accounts, for example, which let people dream of a win without risking their principal. Betting companies should be required to send regular messages that clearly outline a customer’s losses and to monitor for signs of addiction, reaching out when someone is at risk. And just as society once turned smoking into a social taboo, we should make it unthinkable for sports stars to promote betting. As Khaya Dlanga, who lost his brother as a result of sports betting, wrote on X recently: ‘We cannot afford to wait for more suicide notes like my brother’s.’ No public figure should want their face linked to such devastation.

Interventions like these will make a difference at the margins, slowing down the speed of adoption. But they are unlikely to completely reverse the trend.

So here is my more radical – and only half-serious – solution. If we truly want to put the brakes on sports betting, perhaps it’s time to hand the entire industry over to the state. Yes, nationalise it. This is not as far-fetched as it sounds: countries like Sweden, Norway, and several Canadian provinces already run state monopolies on alcohol, precisely to contain the social damage of addictive goods. And in South Africa, there’s an added twist: our government has an unrivalled ability to run even the most robust industries into the ground.

Imagine the same institutional energy of other state-owned entities applied to sports betting. A slow, unreliable, understaffed state bookmaker, running on an ageing IT system, with no slick marketing, no former Springboks in sight, and customer service that closes at 2 pm on Fridays. The odds would be so bad, the site so clunky, and the jackpots so delayed that even the most determined punters would soon lose interest.

There is a serious point here, though. If sports betting is a vice that we as a society would be better off curbing, perhaps the best way is not through ever-more clever regulation, but by draining all the glamour and excitement out of it. A monopoly betting shop, run at the pace of a government department, could do just that.

If we’re going to back something, let it be our sports teams and not our savings. That’s a bet we can all cheer for.

An edited version of this article was published on News24. Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. The image was created with Midjourney v6.

The latest figures are not yet publicly available, so I have estimated a growth rate of between 20% and 40%, which is lower than the previous year.

I'm 100% with you on this one. The socioeconomic impact of this is tremendous and nobody (read: not enough people) seems to care.

Prevention would be better than intervention, right? You'll still need interventions but preventing people from even getting into this would save a lot of agony, grief and money.

It used to be cigarettes and smoking, then alcohol – now it's sportsbetting. It's the same old story over and over.

I don't buy it that sports cannot survive without this: I'm sure they said the same when it got banned in Formula1 and cricket (two sports famously associated with cigarettes and smoking for many decades).

Legislation worked pretty well in that case.

Very insightful, well-researched and well-written, Johan.

I was in matric when sports betting first came to the fore in south africa. I, like many of my friends, actually downloaded one of the apps and placed a few bets. It was incredibly straightforward to sign up, I don’t recall there being any warnings or checks of any kind (if anything, we were incentivised through free bets and the like)… again, for a matric kid, probably barely 18 at the time (if that).

By God’s grace, I never got into it, but I understand how easy it is to get caught in the net. More needs to be done to prevent this! Thank you for bringing this up. A very important conversation that we need to have as a country