The birth of the braai

Happy Heritage Day, South Africa!

‘How do you run a Braaivleisaand?’, JM, a Rand Daily Mail reader, meekly asked in May of 1947.1 ‘Some of us wish to organise a braaivleisaand in aid of a local charity, but we do not want it to be a haphazard affair of casual meat-roasting only. We would like to run it as braaivleisaands should be run.’ Further, JM wondered, what are the origins of the braaivleisaand, ‘when and how did braaivleisaands become such an accepted feature of South African social activity?’

The editor wrote back:

Trenches about a foot deep and six feet long should be dug and overlaid with either a metal grille or a length of flat iron. Put a layer of wood in the trench and overlay it with a layer of coal, and above this another layer of wood. The fire should be lit well in advance, so that the meat can be grilled over the glowing embers. The meat usually used is rib chops and boerewors. For the correct atmosphere, dancing accompanied by a ‘boere-orkes’ is considered to be essential. Beer and coffee should be served.

The answer to the second question proved a little less obvious. Google will tell you the word comes from the Dutch ‘braden’, meaning to roast. The first Afrikaans-language cookbook, EM Dijkman’s 1891 Di Suid-Afrikaans Kook-, Koek-, Resepboek, includes recipes for ‘gebraaide’ meat, using the term in its original sense. This does not mean people were not cooking over open flame. Humans have been cooking with fire for millennia; primatologist Richard Wrangham argues that fire-based cooking is what makes us human. There is even a case that the earliest evidence of controlled-fire cooking is in South Africa, at Wonderwerk Cave in the Northern Cape, dated to around 1,000,000 years ago.2

The more interesting question is when South Africans began treating the braai as a distinct tradition. When did a set of practices emerge to determine how a ‘braaivleisaand should be run’?

The Rand Daily Mail editor did not know either. A popular theory held that it is ‘a survival of, and meant to commemorate, the Voortrekker camp-fires’. This is the same answer reached by 2024 Master’s graduate, Unathi Funde, who appears to have written the only academic history of the braai.3

According to Funde, the braai came to cultural prominence in the 1930s primarily as a fundraising activity. Over the course of that decade, braaiing became more explicitly tied to Afrikaans culture and tradition with the rise of Afrikaner Nationalism, and particularly in connection with the centenary celebrations of the Great Trek. In the run-up to and during the centenary, hundreds of braaivleisaands were held across the country. One event, conducted on the grounds of the Helpmekaar School in Johannesburg, saw a staggering ‘2,000 pounds of sausages, 4,000 pancakes, thousands of mosbolletjies, hundreds of chickens, large quantities of fruit salad and cool drinks, coffee and tea’ served to the 5,000-strong crowd.

The outbreak of war in the mid-century took the braai abroad. South African troops hosted a braaivleisaand in the Italian countryside. By 1947, it had become a national icon. The British Royal Family, on tour of the country in an attempt to keep South Africa in the empire, were treated to a braai in the grasslands of Doornpan, Free State. The occasion was not without its awkward moments, involving, in one instance, Princess Margaret and a flying piece of sosatie meat.4

With the braai’s popularity solidified, it quickly became a commercial object, synonymous with beer and rugby, stereotypically male and unequivocally white. As GM’s famous jingle put it: ‘Braaivleis, rugby, sunny skies and Chevrolet’. By the 1970s, consumers were so burned out on beer-and-braai imagery that, according to Anne Kelk Mager, the head of SAB’s beer marketing division banned all braais in beer adverts.5

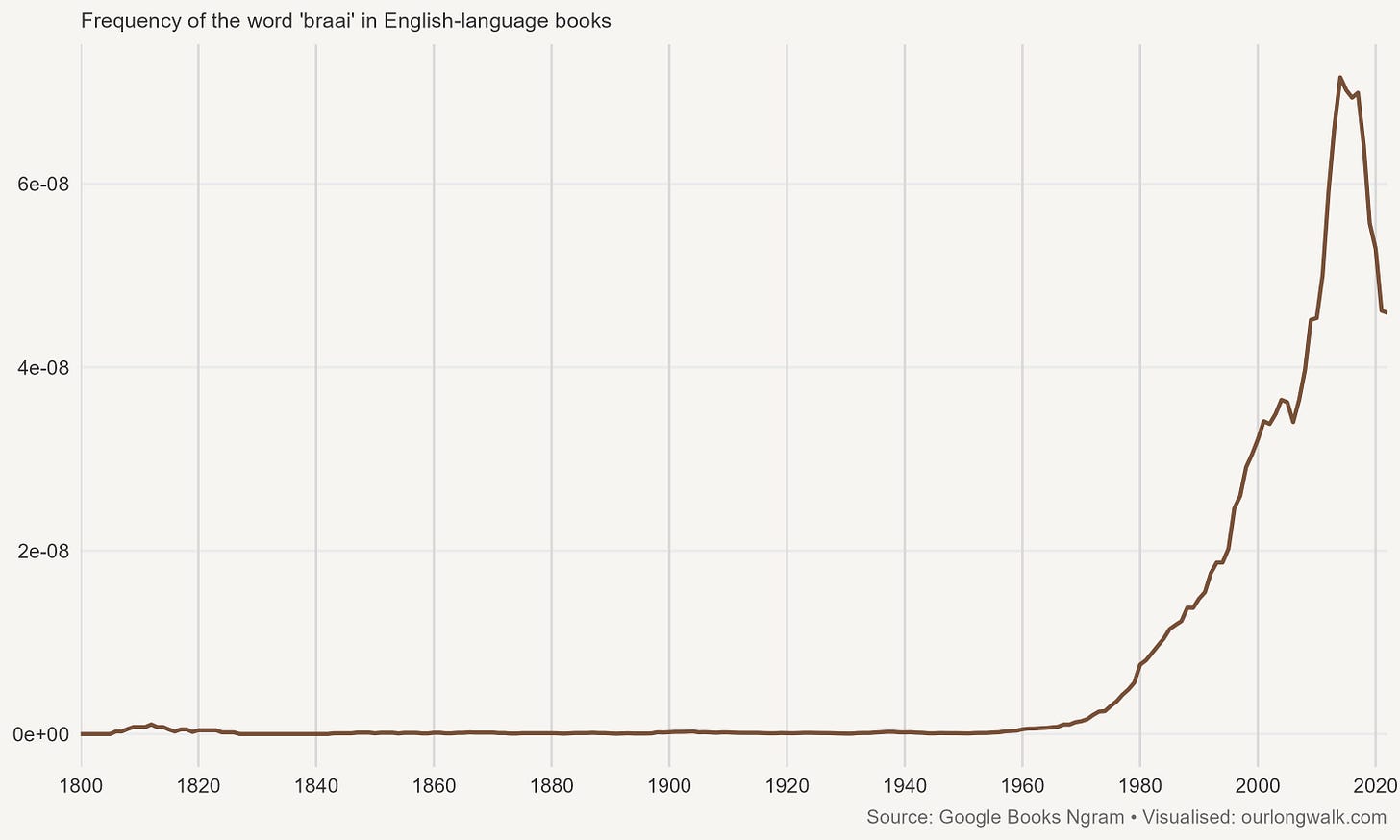

A simple way to trace the braai’s move from a community practice to a wider cultural reference is to look at printed language. A Google Ngram for ‘braai’ in English-language books shows little usage before the 1960s, a gradual rise from the 1980s, and then a sharp climb through the late 1990s and 2000s, with a peak in the early 2010s and a modest decline thereafter. This pattern fits the story above: commercialisation during the late twentieth century, followed by wider public recognition and export into global English. The Ngram measures word frequency in digitised books, not newspapers or oral culture, and it undercounts Afrikaans usage and variants such as ‘braaivleis’. Even so, as a rough proxy for cultural salience in print, it supports the idea that the braai is a relatively recent phenomenon.

With democracy came efforts to universalise the braai. As Duane Jethro observes, the sheer number of braai cookbooks published in the decade after apartheid’s end is testament to the braai’s symbolic, and also commercial, capacity.6

From 2005, accountant-turned-chef Jan Scannell, known as Jan Braai, popularised a new name for Heritage Day: Braai Day. Scannell, with Archbishop Desmond Tutu as Patron, leveraged South Africans’ weakness for grilled meat and recast the braai as a crucible for shared national identity. ‘Countries with strong social cohesion become strong nations’, he argued.7 ‘This is why it is important to celebrate our common national heritage through truly South African features. And what is more South African than shisa nyama?’

Which brings us to a potentially controversial question: what is the difference between a braai and a shisanyama? To the uninitiated, the two are synonymous: meat, smoke, fire. Yet their histories are very different.

According to geographer Christian Rogerson, restaurants referred to as ‘tshisanyama’ (also shisanyama, chesanyama) grew up in and around Johannesburg in the late nineteenth century.8 As some of the only establishments catering to the city’s black workers, they were derogatorily referred to as ‘Native eating houses’ in officialdom. They came to be known colloquially as ‘Shisanyama’. As Daizer Mqhaba put it in verse, ‘The advertisement must be fuming smoke / That is burning meat and pap’.9 These were not sites for celebration. In both the popular imagination and official reports, shisanyama were regarded as noxious. Peter Abrahams wrote derisively in 1954 that ‘Really, the Burning Meat belonged to the flies. But we had nowhere else to eat, so the flies tolerated us.’10

Though central to black working-class life, they were typically run by immigrants, mostly Lithuanian, Greek or Chinese, and struggled under the constraints of apartheid geography. Sometime in the mid-century, the shisanyama gave way to the magnificently named ‘cafes-de-move-on’, coffee carts nimble enough to evade apartheid red tape, at least for a time. In the years since democracy, shisanyama has been reclaimed. No longer the noxious ‘native eating house’, shisanyama is an important part of township food culture and, increasingly, of South African tourism.

Which brings us back to Wednesday: Braai Day. So how do you run a ‘braaivleisaand’ today? I asked Jan Braai for advice:

A defining element of a braai is the wood fire, the bigger the better and if you’re in any doubt whether your fire is big enough then it’s too small. Whichever wood is dry and widely available in your area is the correct wood. Whereas it’s entirely possible to braai alone, a braaivleisaand needs a gathering of people, at least two. For me the social cohesion and consequently nation building properties of a braai sits central to my thought process around the positioning and growth of National Braai Day so this gathering of people around a fire is closer to the core of a braai than exactly what is on the menu. Nonetheless there are some items so unique to a braai that any braaier worth their braai salt should have it on the menu. Boerewors is a uniquely South African invention with spices from the East, sausage making skills from Europe and meat from Africa making it a great analogy for everything that is good about the people of our country. Braaibroodjies, the classic with cheddar, tomatoes, onion, salt, pepper, a thin layer of chutney and buttered on the outside should also be present. Do not discriminate against any animals; include and braai all of them, beef, lamb, chicken and pork. I also consider potjiekos a quintessential braai item and don’t think a braavleisaand will be complete without it.

Braai Day gives the rituals of braai a deeper meaning. Heritage is often mythologised and our origin stories are rarely complete, but they matter because they help people act as a community. Rather than a ‘haphazard affair of casual meat-roasting’, a braaivleisaand is an exercise in cooperation: we share a fire, we share the meat and the stories told while preparing and consuming it. Those stories may be imperfect and incomplete, yet when told to invite rather than exclude, they help build a better South Africa.

To celebrate Heritage Day, I’m giving away a copy of Jan Braai’s Atmosfire to any subscriber who signs up for an annual Our Long Walk subscription until Braai Day (24 September). T&Cs apply.11

“The birth of the braai” was first published on Our Long Walk. The images were created with Midjourney v7. A big thank you to Kelsey Lemon for her research assistance. And to Jan Braai, for taking the time to share some braai advice! Buy his latest book – Atmosfire – at Takealot, Amazon or any good bookshop.

“How do you run a Braaivleisaand?” Rand Daily Mail, 26 May 1947.

Berna, F. et al., 2012. “Microstratigraphic evidence of in situ fire in the Acheulean strata of Wonderwerk Cave, Northern Cape province, South Africa.” PNAS.

Funde, Unathi. "Manning the Braai: Tracing the Gendering of the Braai in the Public Discourse." PhD diss., University of Pretoria, 2024.

Viney, G. 2018. The Last Hurrah: South Africa and the Royal Tour of 1947.

Mager, A.K. 2005. “’One beer, one goal, one nation, one soul’: South African breweries, heritage, masculinity and nationalism, 1960–1999.” Past & Present, 188 (1): 163–94.

Jethro, D. 2020. Heritage formation and the senses in post-Apartheid South Africa.

“Tutu: One nation, one braai.” Mail & Guardian, 2 September 2008. https://mg.co.za/article/2008-09-02-tutu-one-nation-braai

Rogerson, CM. 1988. “’Shisa Nyama’: The rise and fall of the native eating house trade in Johannesburg.” Social Dynamics, 14 (1): 20–33.

Mqhaba, D. 1988. “Tshisa-Nyama.” Staffrider, 7 (3–4): 207–8

Abrahams, P. 1954. Tell Freedom: Memories of Africa.

Offer valid while stocks last. Postage is included but subject to the availability of delivery services in the recipient’s country. Where postal or courier services are not available, delivery cannot be guaranteed. Subscribers will be contacted for delivery details; orders require the timely provision of accurate personal information. Failure to provide such information will result in cancellation of the order. The organiser cannot be held liable for the condition of products supplied by third-party providers (e.g. Amazon, Takealot). No responsibility is accepted for delays, losses or damages arising from postal or courier services. The organiser reserves the right to amend or withdraw this offer at any time without prior notice.

Mouthwatering! Traditional now all round the world.