South Africa's fading relevance

The sooner South Africa confronts its economic stagnation, the sooner it will be able to shape its own destiny

South Africa finds itself at the centre of global attention. This year, it hosts the G20 Summit, a gathering of the world’s most powerful economies. But it’s not just diplomacy that has put the country in the headlines. In the past week alone, Trump has cut off US funding, Musk has revived old accusations about racial policies, and Rubio has refused to attend the G20, citing concerns over expropriation.

South Africa has responded. In his State of the Nation address last week Thursday, President Cyril Ramaphosa dismissed Trump and Musk’s claims, stating unequivocally: ‘We will not be bullied’. He continued: ‘We will stand together as a united nation. We will speak with one voice in defence of our national interest, our sovereignty and our constitutional democracy.’

France, Italy, Germany and the European Union have also made their position clear, voicing strong support for South Africa and reaffirming shared commitments to democracy, human rights, and multilateralism. In a video shared by the EU delegation, European ambassadors highlighted the deep ties between South Africa and the bloc, with France’s representative stating: ‘Just like you, we love our constitutional rights and protection, and we do believe in a non-racial, non-sexist democracy.’ European Council president António Costa went further, expressing the EU’s full backing for South Africa’s leadership of the G20 and its commitment to global cooperation.

This transatlantic divide has drawn international attention. Time Magazine published an analysis titled ‘Why Trump and South Africa Are at Odds’, while the Financial Times compared Musk’s rhetoric to past controversies over state capture in the country. Major media outlets, from CNN and Reuters to Al Jazeera and The Guardian, have dissected the fallout, each framing the dispute through their own geopolitical lens.

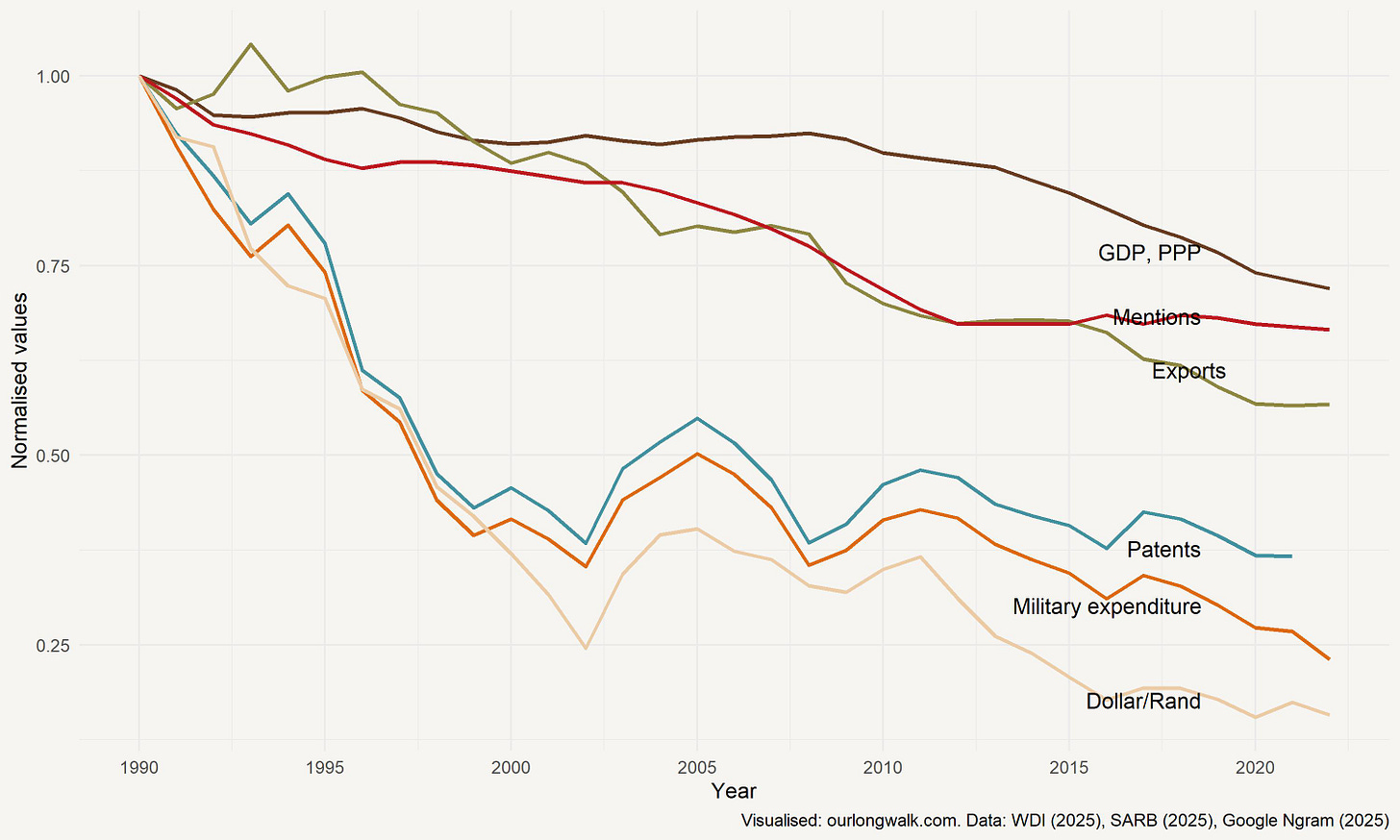

Yet much of this debate misses a key point: South Africa has failed to live up to its economic potential. Take the following graph.

It tracks six indicators of power: GDP, exports, patents, military expenditure, the exchange rate (against the dollar), and even how often ‘South Africa’ appears in books. Each measure is calculated as a share of the global total and then normalised to 1 in 1990.

The numbers tell a sobering story. South Africa’s share of global GDP and exports has steadily declined, while patents, military expenditure, and the rand’s value against the dollar collapsed in the 1990s and have never recovered. (Patents and military spending, intriguingly, follow almost identical trajectories—an eerie correlation that speaks to the country’s shifting priorities.) Even cultural relevance, measured by mentions in English-language books, has faded.

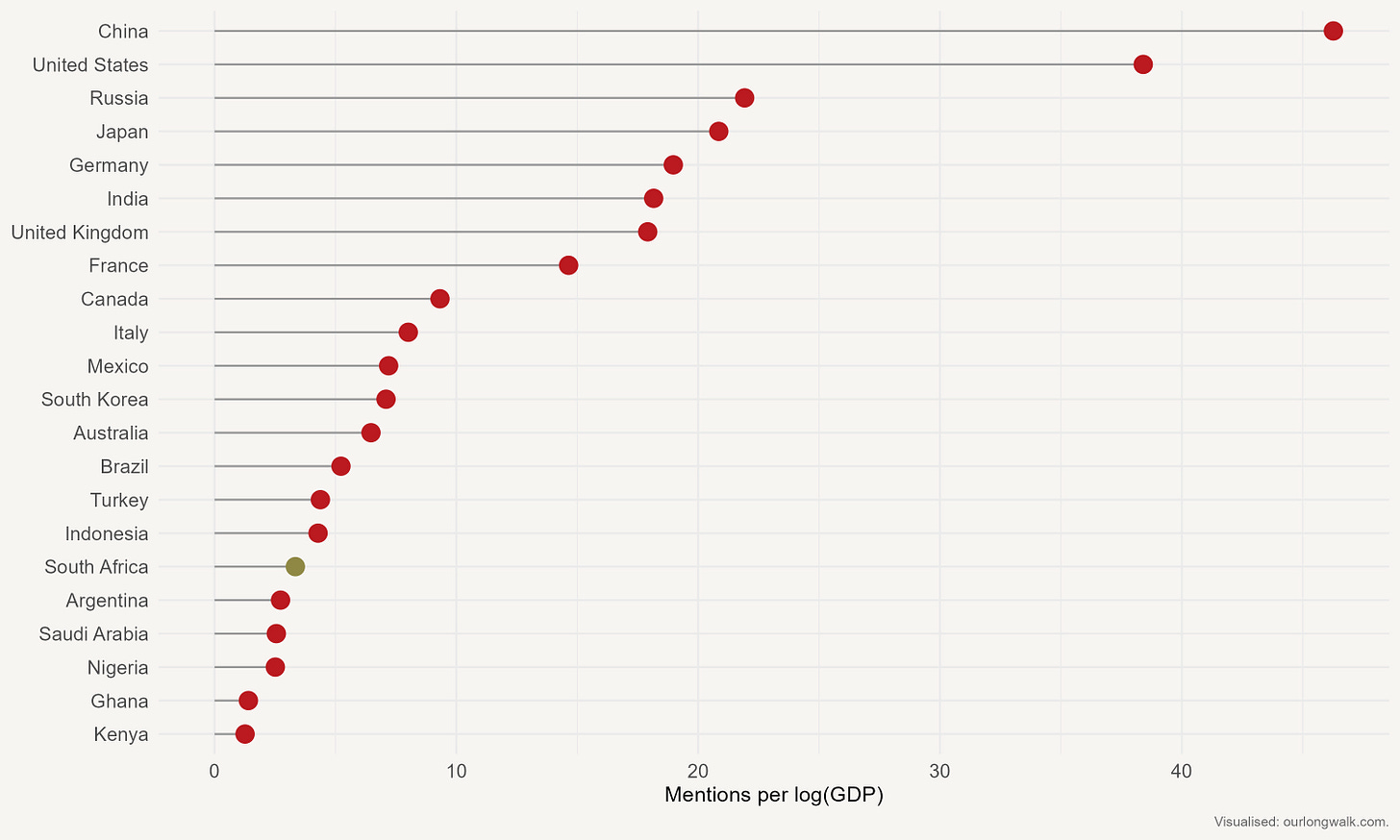

Or, to give a cross-country perspective, here is the frequency at which the G20 (plus Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya) are mentioned in thirteen popular economics/investor blogs, totaling 1361 total posts, on Substack since 2021.1 South Africa is clearly an underperformer.

Another way to express this is to take the number of mentions and divide it by log(GDP). The results are provided below. Of all the G20 countries, only Argentina and Saudi Arabia attract less attention in popular Substack economics/investment blogs than South Africa.

Peter Bruce captured the mood in Business Day: ‘SA has fallen so far down the global investment chain that hardly anyone asks why any more.’ Speak to investors abroad, and South Africa barely registers. Once a rising economic power and Africa’s obvious gateway for capital, it now competes for investment against countries that offer more predictable policies, even within its own continent.

Some of this drift is by design. Under Ramaphosa, South Africa has sought to carve out a role as a diplomatic heavyweight – leading ceasefire efforts in Ukraine, deploying peacekeepers across Africa and taking Israel to the International Court of Justice. Its stint on the UN Security Council reinforced its ambition to be a leading voice for the Global South. Ramaphosa, more than any of his predecessors, sees himself as a broker, a statesman willing to mediate where others hesitate.

But without economic muscle, talk is cheap. Why South Africa has failed to live up to its economic potential is the real issue that should be under discussion, both at home and abroad. Perhaps that is the lesson we should take from this dispute with Trump and his ilk: standing firm against a bully is admirable, but a bully thrives on weakness. And South Africa – with its deep-seated corruption that hollowed out state institutions, drained resources and crippled Eskom, cronyism that collapsed service delivery in many municipalities, and its tangled web of labour laws that stifle rather than empower entrepreneurs – has made itself an easy target.

The Government of National Unity offers a chance to reset. Economic growth empowers a nation to chart its own course rather than be pressured into following another’s agenda. The sooner South Africa tackles its economic stagnation, the sooner it can reclaim control over its future.

‘Fading relevance’ was first published on Our Long Walk. Thank you for your subscription. The image was created with Midjourney v6.

I thank Lisa-Cheree Martin for excellent research assistance in scraping the following popular Substack blogs: adamtooze, africanistperspective, arpitrage, braddelong, doomberg, global-developments, netinterest, noahpinion, sustainabilitybynumbers, thebignewsletter, thegeneralist, theovershoot and unevenandcombinedthoughts. Only publicly accessible (unpaid) posts were scraped.

Johan you have a lense that you obviously subscribe to but nowhere in your musings are you talking about the obvious issue here. Deliberate dis-investment by the state. Government has been on a spending freeze (more popularly known as fiscal consolidation)since 2012 which is at the centre of why the state can’t make good on any of its promises. This is not me saying this is Michael Sachs (former ddg of budget at national treasury). The rating agencies have gone as far as confirming this view; there is no local demand in otherword there is no local investment. Which is obviously driven by public spending. When was the last time you saw a large infrastructure spend in the country ? Look at the size of the construction companies now shadows of their former selves. You are shocking me quoting Peter Bruce as if he is some authority in economics. You are skirting past important issues by rehashing popular narratives that actually don’t fit at all. You speak of cronyism etc what is happening in the US ? Is that going to impede job creation, economic growth etc. No why ? Because corruption is a rounding error in the grand scheme of a countries development.