Rich prof, poor prof

Should we be worried about the concentration of economics research in the Ivy League?

I have a good idea. In fact, it might be a great idea. It is an idea I have not seen in any of the top economics journals, an idea that could move a field forward.

Now the hard part begins.

First I have to turn that idea into a research design. That means finding data, or collecting it myself. If it is historical, it probably lives in dusty archives or badly scanned PDFs. If it is contemporary, it might require a survey, a randomised trial, or persuading a reluctant ministry to share administrative records. All of this takes time and money. More importantly, it has to be done in a way that will later satisfy referees who think about nothing but identification. They will ask whether my variation is really exogenous, whether I have the right fixed effects, whether I have controlled for the unobservable that some future PhD student will name after themselves.

Suppose I get past the data problem. I still need to write the paper in a register that a top journal expects. And before I even think of submitting, I have to present it in seminar rooms where the entire audience has one goal in mind: to break the paper apart. Every slide invites attack. Why that instrument, why that functional form, why stop the sample in 2012, what about this alternative explanation you conveniently forgot to mention?

Each time I present, I go back to my desk, rewrite sections, rerun regressions, collect extra variables. After a dozen of these sessions, the paper is unrecognisable from the one I started with. The identification is tighter, the theory cleaner, the robustness section fatter. Only then, when the paper feels almost bulletproof, do I consider submitting it to a top journal.

And then I wait.

If I am lucky, a few months later I receive feedback from three or four or five anonymous referees and an editor. They share the same incentives as the seminar audience. They want to accept only the very best, because only the most inventive papers, the ones most likely to push the field forward, will be widely cited, and citations are the currency of journals. Most papers fail that test. So my paper is rejected and I start again with another journal, and another round of waiting, another set of comments, another round of revisions. The process can easily take three to five years. For a single paper.

This is the background against which we should read the new study by Ernest Aigner, Jacob Greenspon and Dani Rodrik in World Development. They assemble data on hundreds of thousands of articles in economics and business journals since 1980. Their conclusion is stark: authors based in poorer countries are spectacularly under-represented in the leading journals. Even controlling for citations, they find that ‘articles by developing country authors are far less likely to be published in top journals’ and that authors in these countries ‘remain excluded from the profession’s top-rated journals’.

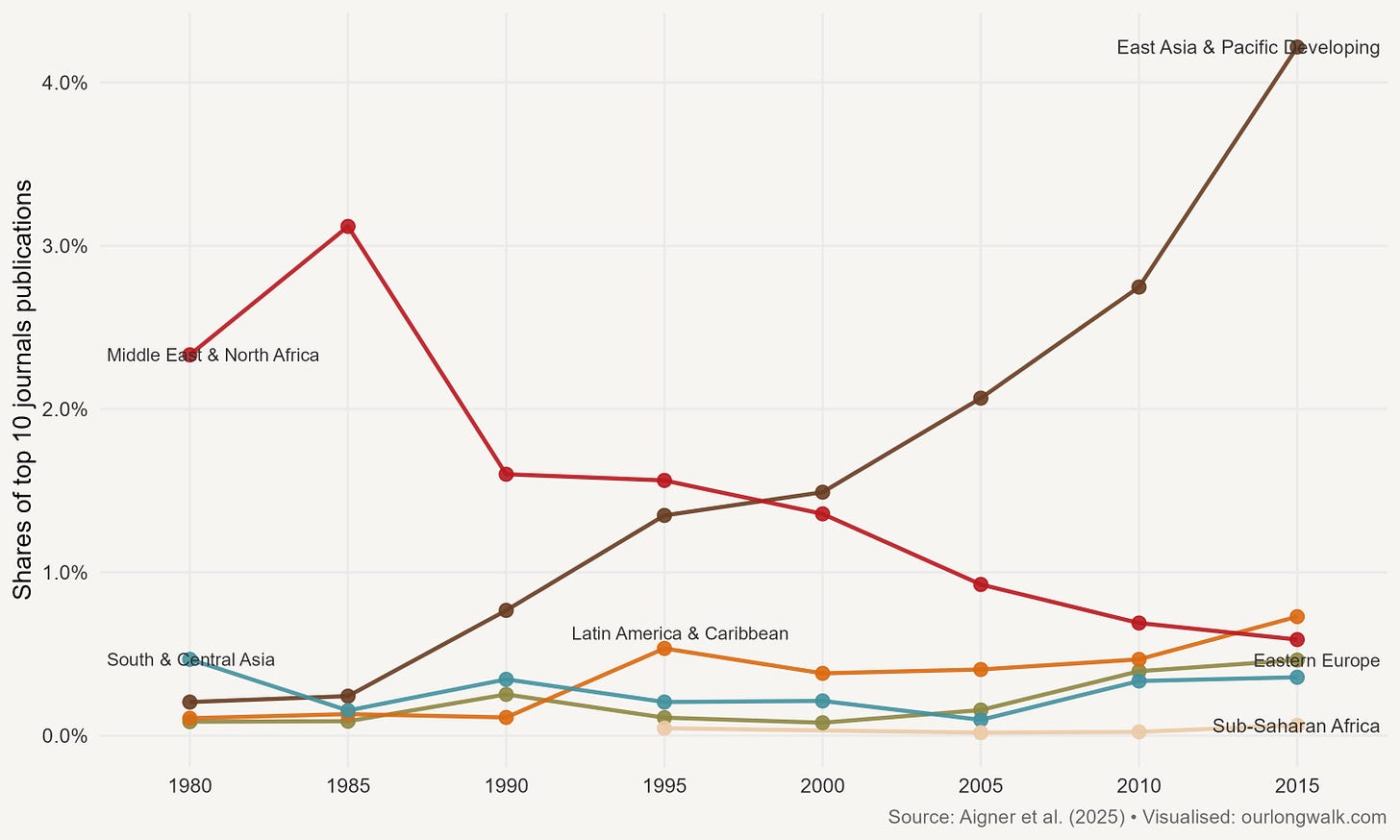

The figure I reproduce here shows the share of articles in the top ten economics journals written by authors based in different developing regions. One line jumps out: East Asia and the Pacific. From almost nothing in the 1980s it has risen to around four per cent of top-ten authorship in recent years. Other regions barely register. Latin America bobs along close to one per cent. South and Central Asia creeps up from almost zero to not much more. Sub-Saharan Africa is a thin, flat yellow line on the x-axis.

It is no surprise that many academics outside the rich world look at this graph and feel anger. The comments on social media were full of them. The field is rigged, they say. Economics is an elitist discipline. The top journals are a cartel. The system is structurally unfair to scholars in poorer countries.

I understand the sentiment, but I think it is the wrong interpretation.

I do not deny that editors and referees have biases, intentional or not. Economists usually distinguish between taste-based discrimination – preferring one group over another simply because of who they are – and statistical discrimination, where decisions are based on crude proxies because information is imperfect. If an editor sees two submissions, one from Stanford and one from Stellenbosch, it is easy for those of us in the global South to experience any preference for the Stanford paper as taste discrimination against us – and in some cases it might be just that. But there is also a statistical logic at work: on average, a Stanford PhD is more likely to have survived exactly the humiliations I described above. The polished draft that lands on the editor’s desk is often the survivor of a brutal internal competition, and affiliation becomes a noisy signal of that process. The deeper problem, especially in African departments, is that we often do not give our own ideas the same chance to survive an equally demanding winnowing before they reach the editor’s inbox.

That is partly about resources, but it is also about incentives. As I’ve explained before, in almost all African universities, quantity is favoured over quality. A long CV of local conference proceedings or low-tier publications counts more for promotion than one good paper in an international journal. In South Africa, we rarely attract the very best students into our graduate programmes, for a variety of reasons, and when we do, we often prepare them for jobs in government or consulting. We limit our appointments to locals, even though there are very few (South) Africans who have trained at the best US departments. For a mix of historical, political and bureaucratic reasons, we remain isolated from the international economics community.

It is easy to blame ‘the West’ – or America, or the Ivy League – for the inequalities that Aigner and co-authors expose. It is much harder, but ultimately more productive, to look in the mirror. Our biggest problems are often our own institutions and the incentives we create.

The good news is that change is possible. The same figure that depresses us about Africa gives us a hopeful example in East Asia. Look at the purple line. From the mid-1990s onward, authors based in East Asia and the Pacific steadily increase their share of top-ten publications. China is the main driver. What did they do? They sent thousands of students to study economics in the United States. They still do. Many stayed on in American universities. Many more returned and began to emulate the practices of their professors. They built seminar cultures. They rewarded publication in good journals. They hired internationally. Today it is not at all fanciful to imagine a Chinese economics department breaking into the global top ten. The race is still uneven, but they are at least on the same track.

This raises a more fundamental question. Is the concentration of economics in a few US departments necessarily a bad thing? Commentators often take it as obvious that it must be. Nobel laureates in economics are far more concentrated at a handful of institutions than Nobel winners in physics or medicine. Surely that is unhealthy.

First, it is worth remembering who these ‘Stanford’ or ‘MIT’ economists often are. Many of the brightest minds in the discipline today grew up in the very countries that feel excluded. 2019 Nobel laureate Abhijit Banerjee, who will move from MIT to Zurich next year, was born in India. After a degree at the University of Calcutta, he moved to Harvard for a PhD, and has worked on a range of issues in developing countries since. Harvard’s economics department today includes Raj Chetty, Gita Gopinath and David Yang – all world-class scholars whose life stories begin far from Cambridge, Massachusetts. The concentration is therefore less one of nationality than of institution.

Second, part of the work that won this year’s Nobel prize, by Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, suggests why concentration might actually be a good thing. In their models of growth through innovation, firms invest in research in order to gain a temporary lead over their rivals. The key insight is that innovation is strongest when competitors are ‘neck and neck’. If the market is perfectly competitive, profits are too small to justify risky innovation. If a single firm is a secure monopolist, it can relax. It is when several firms are close, each fearing that the others will overtake them, that innovation flourishes. The relationship between competition and innovation takes the shape of an inverted U: too little competition is bad, but so is too much.

Seen through this lens, a concentration of talent at a few elite universities can actually foster innovation. If Harvard, MIT, Chicago and the rest are all producing PhDs who are desperate to outdo each other, they create exactly the ‘neck-and-neck’ conditions that Aghion and Howitt describe. The seminars are fierce, the expectations sky-high, the fear of being scooped ever-present. That is not a cartel. It is a cauldron. From the outside it may look like an oligopoly. From the inside it feels like an arms race.

Would it be good to see more Africans in that race, publishing in the top journals and winning prizes? Absolutely. Should we expect the current leaders to lower their standards or handicap themselves to make room for us? I do not think so. The better approach is to ask what we can learn from places like China about building more competitive local university systems. We need departments where ambitious ideas are not only tolerated but stress-tested, where students are pushed to compete with the best in the world, where appointments are made on merit, not nationality or clan, and where a brilliant PhD student from Kampala or Karachi is just as likely to end up a global star as one from Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The inequalities that Aigner and his co-authors document are real. But they are not a reason to despair or to retreat into a language of rigging and exclusion. They are a challenge to remake our own institutions – how we hire, how we promote, how we train students and reward research. If we get that right, the next groundbreaking idea born in Africa will not be buried under teaching loads, box-ticking publication targets or bureaucratic constraints. It will be sharpened, tested against the best in the world, and sent into the same unforgiving tournament that every other good paper faces.

‘Rich prof, poor prof’ was first published on Our Long Walk. The images were created with Midjourney v7.

Great piece! Competition in the scholarship of Economics has similar effects as competition among the field's subjects: industrial competitors.

I agree, and I'll add another factor. Economists have good options outside academia. There are great potential researchers, born in these countries, who get filtered out of top universities but take private sector jobs.