Quota calamity

How rigid hiring rules could strangle South Africa’s economic future

Imagine you run a radar company in Hermanus.1 Your drones use advanced sensors to track rhino poachers across vast wilderness reserves. The technology is local, and your team of 60 engineers is lean and highly skilled, most with advanced degrees from a nearby university. These roles are not easy to fill. The skills are globally in demand, and many of your staff could work abroad. They stay because they value life in a coastal town with good infrastructure, a competitive salary, and a project they believe in. Forty-two of them classify as white. Six as female. That means 70 percent of employees are white and 90 percent are male. The team reflects a legacy of uneven access to specialised training. Now, with international demand growing and a European contract secured, the company is preparing to expand.

Then the new employment equity regulations arrive.

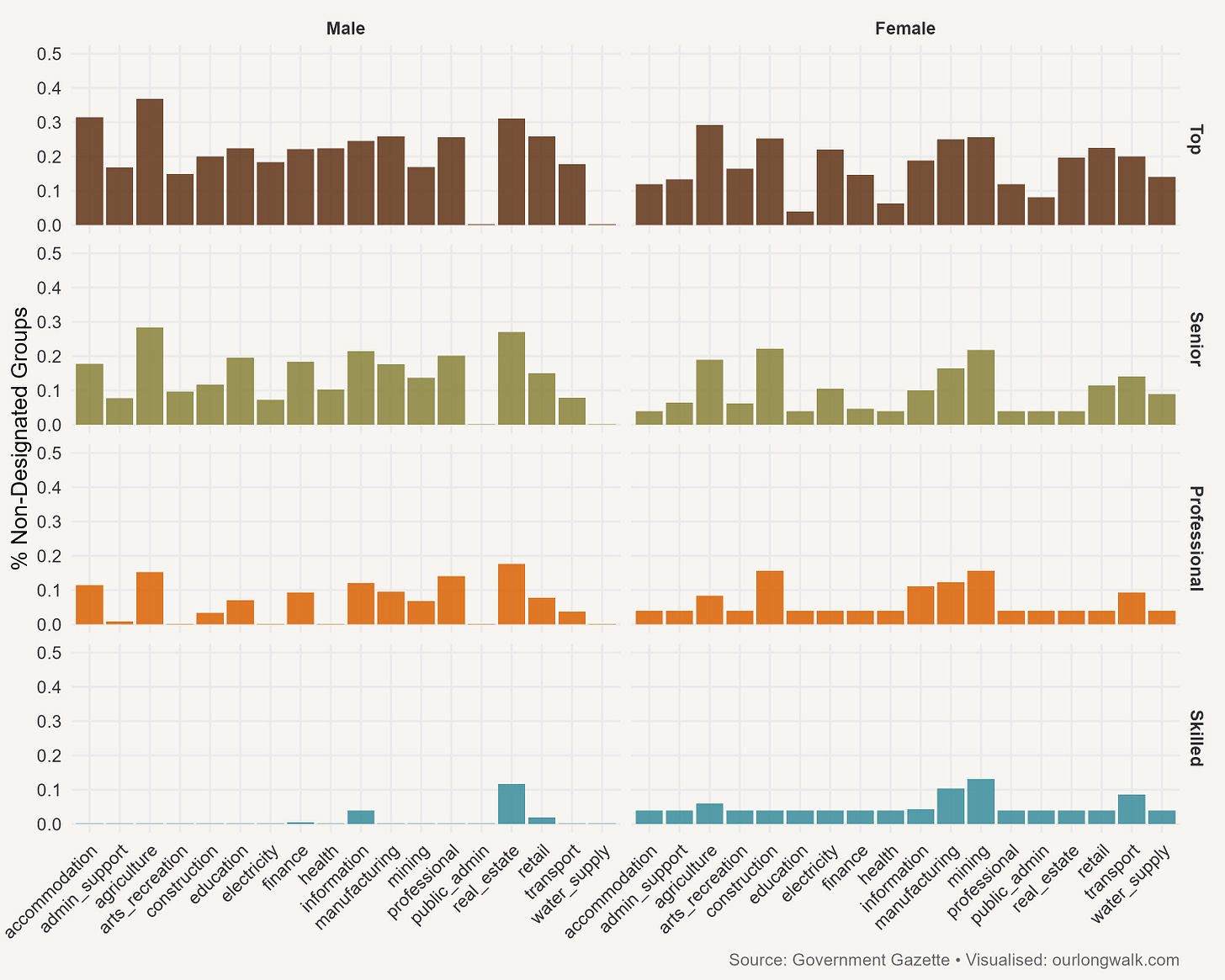

According to the Determination of Sectoral Numerical Targets of the Employment Equity Act, any South African company with more than 50 employees must ensure its workforce mirrors the national demographic profile across four occupational levels and eighteen sectors. In your industry, as shown in the graph below, professionally qualified white males may constitute no more than eighteen percent of staff. In top management, you may only be 38.5 percent white.

As CEO, the reality you face is that meeting these targets would require your next 140 hires to exclude white males, with 115 drawn from black, coloured or Indian groups.

The goal, of course, is not without justification. South Africa’s past excluded most from opportunity. Racial transformation remains a necessity. But the shift from broad planning to rigid, enforceable quotas changes the nature of the project. What has shifted is not intent, but method – and the costs.

Even setting aside philosophical questions about what it means to be ‘white’ in a country like South Africa – see my recent interview with Princeton historian Jacob Dlamini – the economics of these targets, or quotas, are troubling. A recent paper by David Baqaee and Kunal Sangani, Quotas in General Equilibrium, offers a framework for understanding the consequences.2 Quotas restrict quantities rather than prices. This distorts how labour and resources are allocated, forcing the economy below its potential.

In markets, prices guide resources. Quotas override this mechanism. When they bind – as these regulations inevitably will – they cause misallocation. Baqaee and Sangani illustrate this with real-world examples: easing US visa caps, scrapping zoning limits and lifting import quotas. In each case, removing constraints raised productivity. Applied to South Africa’s new rules, the effect is the same. Hiring based on rigid targets, rather than skill or need, leads to underperformance. Some roles are filled by less-qualified staff. Where no suitable candidates are available, positions remain unfilled. The result is a labour market that struggles to match people to jobs. Output falls accordingly.

There are several reasons these losses compound.

First, national targets take little account of local variation. South Africa’s population is diverse not only by race, but by geography. Towns and regions differ widely in their demographic composition. Yet the employment equity benchmarks are applied uniformly across the country. In Hermanus, for example, more than 80 percent of the population was classified as white in the 2011 census. A radar company based there is unlikely to find a large pool of black engineers in the immediate area. This makes compliance not only difficult but potentially unachievable without relocation or artificial restructuring. Firms are then penalised not for discrimination, but for geography.

Second, labour market signals falter, weakening incentives to invest in skills. For a young white man, the message is clear: in sectors like public administration or water services, where the allowable share of non-designated appointments is 0.2 percent per tier, a career in the field may appear futile. Fewer will train for roles they have little chance of occupying, deepening shortages further. Those with existing skills may simply move abroad. The country loses not just talent, but its investment in education.

Ironically, these constraints may lead those from overrepresented groups to start their own businesses instead. Doing so means that hiring rules are less restrictive and the potential rewards can be higher, even if more uncertain. At the same time, those from underrepresented groups may be more drawn to the stability and better pay of corporate jobs, making them less likely to take the risk of starting something new. The unintended result could be that the very groups the policy aims to uplift become less represented in the most dynamic part of the economy: new and growing businesses.

Third, firms may respond in ways that limit growth and reduce dynamism. Some will avoid crossing the 50-employee threshold. (An ideal threshold, incidentally, for economists searching for a future regression discontinuity.) Others may restructure into smaller legal entities, automate or outsource to ease compliance. A few may leave regulated sectors altogether. Evidence from other countries supports these concerns. In Saudi Arabia, a similar quota system increased local employment but also led to business closures, nominal hires and weaker exports. One study found that affected firms saw a 14 percent drop in export value. Many retained so-called ghost employees – on the payroll to meet targets, but contributing little to output.3 These are deadweight costs, with wages paid but no productivity gained. South Africa risks repeating this pattern, where performance takes a back seat to statistical compliance.

Finally, investment slows. The law allows the Minister of Labour to revise thresholds and targets at any time. This creates regime uncertainty. Businesses cannot plan under shifting rules. And investment requires confidence in the future.

Together, these pressures amount to a structural misallocation of talent. Baqaee and Sangani’s model shows how this kind of misalignment multiplies across an economy. What results is not stagnation for lack of ambition or capital, but for lack of flexibility in how talent is allowed to flow.

Again, none of this argues against racial transformation of the economy. But transformation depends on economic growth. And growth depends on getting the basics right. Reliable electricity, working rail and ports, safe roads, a secure business environment are not grand ambitions. That is where we ought to begin. A stable regulatory framework, with clear and enabling rules, would do far more to expand opportunity than a rigid matrix of demographic targets.

The radar firm in Hermanus may or may not find a way to comply. But its choices will now hinge less on innovation or market demand, and more on its alignment with a national staffing formula. The cost of that alignment – in time, in talent, in lost opportunity – may not be visible in any single spreadsheet. But it will appear in aggregate, as lower profits (and tax revenue), fewer jobs and slower growth.

We speak often in South Africa of poaching – of endangered species, of scarce resources. But sometimes, opportunity is poached too. Quietly. Through a Kafkaesque set of policy rules that make it harder to hire, to grow, to build a prosperous society.

South Africa cannot afford to let policy become the poacher. Not now. Not again.

An edited version of this article was published on News24. Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. The image was created with Midjourney v6.

This is a fictional company, though it shares many features with real South African firms operating in high-skill, specialist sectors.

Baqaee, D. and Sangani, K., 2025. Quotas in General Equilibrium (No. w33695). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Cortés, P., Kasoolu, S. and Pan, C., 2023. Labor market nationalization policies and exporting firm outcomes: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 71(4), pp.1397-1426.

I cannot help thinking that white South African business leaders have had basically a generation to make this right, and have not. Surely, they saw hiring equity coming as early as 1991. It was only a matter of time. Perhaps they should have considered scholarship programs to help the "underprivileged" get the education they would need in order to compete in the job market. There were plenty of ways business leaders could have assisted in the transformation of South Africa. Government, particularly one that probably has more than its fair share of corruption, can not be expected to solve every problem. Thirty-four years and business owners are only now confronting this? That is shameful.