How Swifties can save the world

Look What You Made Me Do

Welcome to 2025! I’m back from holiday and ready for a jam-packed year of posts about South Africa’s (and global) economic past, present, and future. If you’re a recent subscriber, welcome to Our Long Walk!

Here’s a topic I’m sure found its way into every Christmas conversation: overpopulation, the idea that there are too many people on earth and that we are heading for a crisis.

The idea remains incredibly popular. Whenever I give a talk about our future challenges, there’s almost always someone who brings up Africa’s high fertility rates –or, if they’re being more tactful, praises China’s one-child policy.

What’s striking, though, is how few people who make these points seem to know why they hold these views. What they don’t know is that they’re views are the product of one influential book, The Population Bomb, written by Paul and Anne Ehrlich in 1968. An instant bestseller, the Ehrlich’s shaped how most of us think about population, food supply and fertility policies. The book conditioned an entire generation to see overpopulation as humanity’s greatest threat.

The Ehrlichs proposed drastic solutions: ‘We must rapidly bring the world population under control, reducing growth to zero or even negative. At the same time, we must greatly increase food production.’ It was the 18th-century cleric Thomas Malthus – who also predicted that agricultural output wouldn’t be able to keep pace with exponential population growth – on steroids.

But, like Malthus, the Ehrlichs got it all wrong. Nearly six decades later, their predictions of doom have not materialised. The book’s alarm came just as global population growth peaked, yet instead of famine, disease and unrest, the world entered one of its most prosperous and peaceful periods. Famines, such as those in the Horn of Africa, often stemmed from politics, not food shortages. Statistics back it up: the global annual death rate fell dramatically, from 13.52 per 1,000 people in 1968 to 8.76 in 2021.

As I explain in a new chapter in Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom, the second edition of my book, out in January, their forecasts for India were especially bleak. The Ehrlichs claimed India couldn’t support 200 million more people by 1980 and even suggested cutting aid if it didn’t adopt fertility controls, a move that would have triggered mass famine. Fast forward to April 2023: India overtook China as the most populous country. Meanwhile, China, which took population control seriously, now grapples with the challenges of an ageing population, of which there are many.

China is one of many countries now suffering from the reverse crisis: a dearth of babies. On Christmas day two years ago, The Korea Herald reported:

In perhaps another sign of the country’s declining number of births, South Korea’s largest online marketplace reported Monday that sales of pet strollers exceeded those of baby strollers for the first time this year.

As of 2024, South Korea’s fertility rate stands at just 0.68 births per woman. Keep in mind that, to maintain a population, the replacement-level fertility rate needs to be 2.1. The consequences of such a shockingly low rate are dire: If a generation of 50 million people maintains this rate, the next generation will shrink to only 17 million. Their grandchildren? Around 5.8 million. Great-grandchildren? Just 2 million. At this pace, Korea faces the stark prospect of vanishing within a few generations, a blip in the long arch of history.

Though South Korea is the extreme, it is not alone: fertility rates are plummeting globally. A massive study – with 1406 authors – published in The Lancet earlier this year found that fertility rates have declined in every single country since 1950, with TFR remaining above replacement level in fewer than half of all countries by 2021. When today’s babies are adults, the world will begin to shrink, and so, too, will many economies.

One cannot ignore, then, that when it comes to the future wealth of nations, fertility rates today matter. A new measure, first proposed in the blog Atoms vs Bits, attempts to account for that. It uses Einstein’s elegant E=mc^2 formula and converts it into a Baby Money Index (BMI). Perhaps I might have chosen a different name – the Endowment equation? – I think it has real value. I particularly like that it squares fertility, accounting for the fact that today’s birth rates do not just determine the size of the next generation but the one that follows.

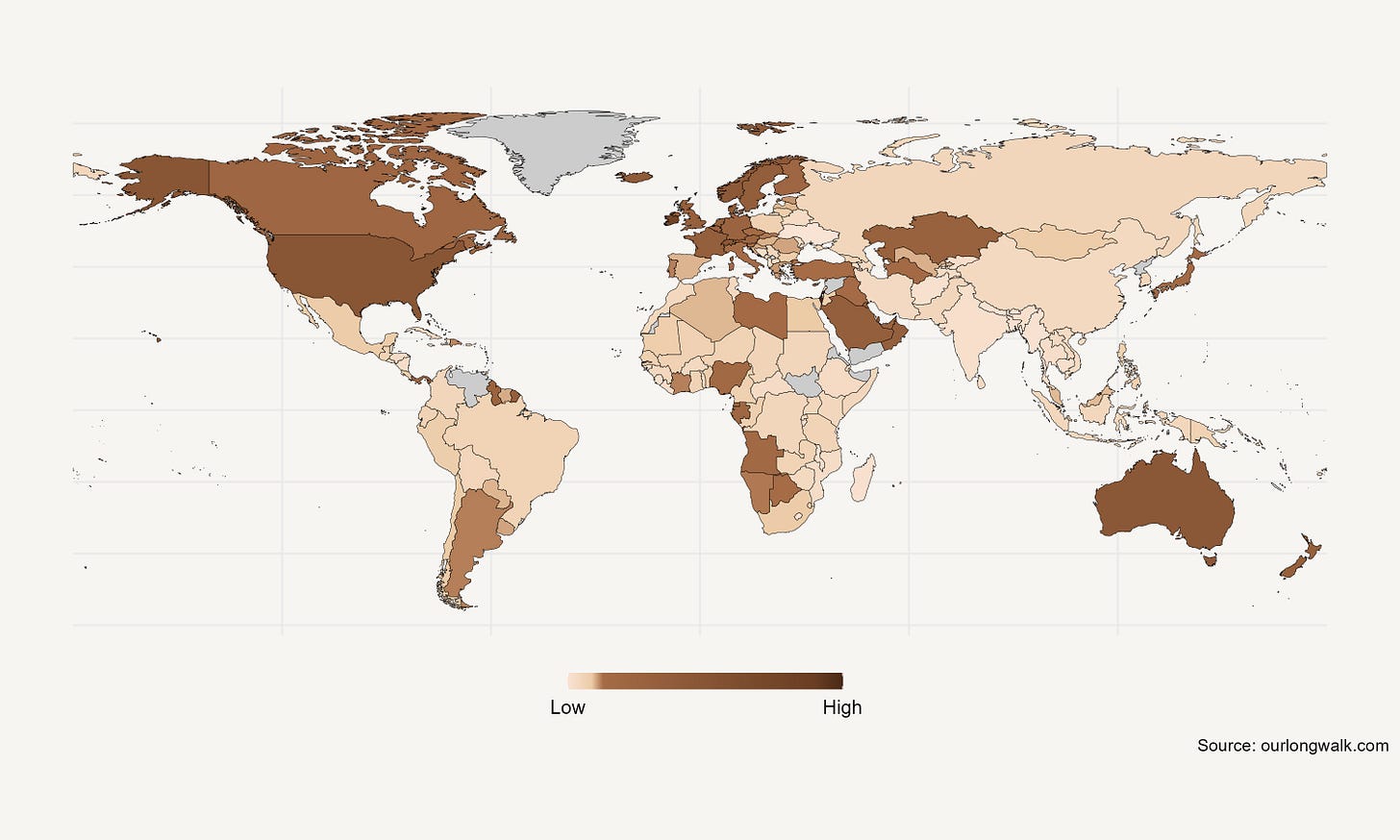

Using World Bank data, I mapped the best-performing countries on the BMI index, using GDP as a proxy for GNI since the two are closely correlated. The results were striking: not only do China and India rank low due to their modest GDP levels, but much of Southeast Asia also falls surprisingly short. While this measure likely gives too much credit to petrostates, it still offers a valuable thought experiment, suggesting that, despite the Indian Ocean’s promising growth, the Atlantic remains poised to lead the way.

So how can a country improve its future wealth? Economic growth is, of course, a good start. But fertility is tricker. The thing is, we don’t really have a good sense of which policies best promote higher fertility rates. As The Lancet article makes clear, in the last seventy years, only three countries rebounded above replacement levels after going below. Daniel Hess of the More Births blog argues that financial incentives like baby bonuses, paid leave and subsidised childcare have not had the desired impact, as demonstrated by persistently low rates in countries like Germany, Sweden, and Finland. He suggests that alternative approaches, such as promoting pronatalist messaging, improving housing policies to favour family-friendly developments (suburbs!), and addressing issues like over-regulation in childcare and medically unnecessary C-sections, offer some potential for boosting birthrates. What is needed, perhaps, is a cultural shift too: encouraging marriage, protecting religious freedom, fostering awareness about fertility challenges, and elevating role models who celebrate and embrace having larger families.

Though much has been written about Taylor Swift’s economic impact – it even has a name: Swiftonomics – maybe the best she could do for the future wealth of nations is to have a kid – and inspire an entire generation to do the same.

Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. The images were created with Midjourney v6.

But what is wrong with economies shrinking if per capita GDP remains constant or even grows (which I suspect will happen in the case of the East Asian economies like Korea and Japan). Yes there may be challenges with an ageing population but in my admittedly anecdotal experience, most people see complete retirement (i.e., relying entirely on income from pension/retirement product) as a historical relic. To me it seems like an early death warrant in any case (excuse the crudeness, just my honest thoughts).

In my experience the fertility "crisis" is far more worried about than the overpopulation one. But neither seem to me to be a crisis.

Assumptions about fertility rates remaining constant at below replacement rate seem as naive as assuming growth rates will continue forever. Birth rates have fallen across the globe regardless of any policy around reducing birth rates.

I think it's safe to assume when people reduce, there's more space, opportunity, housing, land, etc, then behaviour will change again and birth rates will grow again organically. Maybe there is just a natural population equilibrium.

But I'm still open to any arguments about the why reduced fertility is indeed a crisis situation. Just not convinced yet.