Population pressures

One thing South Africans don't have to worry about

In 1968, one of the most explosive books of the twentieth century began with: ‘The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate...’

The Population Bomb, written by Paul Ehrlich and Anne Howland Ehrlich, became an immediate bestseller. It brought unprecedented attention to food supply and, most directly, measures at combating fertility. The Ehrlich’s had their own proposals to defuse the bomb: ‘We must rapidly bring the world population under control, reducing the growth rate to zero or making it negative. Conscious regulation of human numbers must be achieved. Simultaneously we must, at least temporarily, greatly increase our food production.’

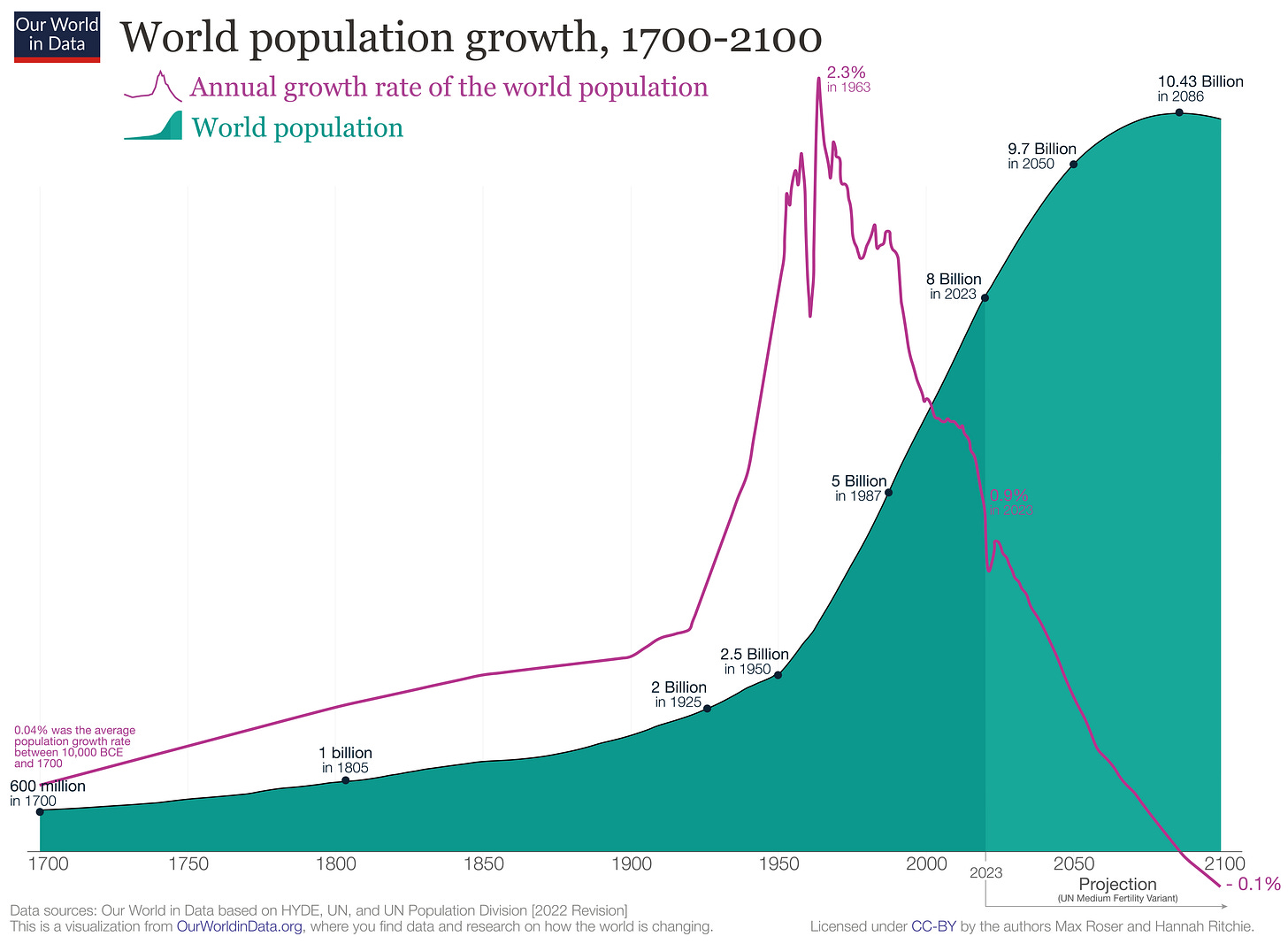

Now, fifty-five years after its publication, the world looks very different. The Ehrlichs made their grim predictions at exactly the time that global population growth rate, the difference between the number of people born and the number of people dying, was at its maximum. As it turns out, their predictions were dead wrong. In the simplest terms, they got the numbers wrong: the global annual crude death rate in 1968 was 12.46 per 1000 people, and in 2020 it was 7.71. Instead of widespread famine, disease and social unrest, the world experienced one of the most prosperous and peaceful periods in human history. Famines, such as those in the Horn of Africa, were often more the result of politics than production.

They were especially wrong about India. In The Population Bomb, the Ehrlichs wrote: ‘India couldn’t possibly feed two hundred million more people by 1980.’ They went as far as to propose that aid should be cut off from India if they did not implement fertility control, a proposal that would have certainly created the conditions for famine. Last week, the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs said in a statement that India’s population will reach 1,425,775,850 people by the end of April, matching and then surpassing the population of mainland China, a country that did take Ehrlich’s predictions to heart and enacted population control measures. While India is now the most populous country on earth, China has serious concerns about an ageing population, as I’ll discuss below.

You would think that this mere fact would humble the Ehrlichs against making future predictions. But you would be wrong. Earlier this year, Paul Ehrlich appeared on the American TV show 60 Minutes, saying: ‘The next few decades will be the end of the kind of civilisation we’re used to.’ It is an argument that still appeals to many.

Because of my books, I frequently speak to audiences across the country. When I ask them to name future threats to humanity, overpopulation is inevitably one of the first mentioned. It is that same fear that the Ehrlichs exploited.

They were not the first to do so. Already in the late eighteenth century, the Reverend Thomas Malthus explained why food production was an inevitable barrier to population growth. When a country’s population grows faster than its ability to produce food, he noted, competition for resources increases, and living standards decline. As a result, wages decrease, and people must work harder to earn the same amount. During these difficult times, there are positive and preventative checks. Famine, war and disease are the ‘positive’ checks, as Malthus called it. People are also discouraged from having children by adjusting their fertility, and population growth slows down. The slower population growth allows wages to increase again, and as things improve, people start having more children again, and the cycle repeats. What does that mean? Malthus believed that the world’s population would grow faster than its ability to produce food, leading to famine, poverty and suffering.

Just like the Ehrlichs’ predictions in the 1960s, Malthus could not imagine that the Industrial Revolution would overturn his predictions. The world population was 1 billion when he published An Essay of the Principle of Population. In November 2022, we reached 8 billion people, living at much higher living standards, on average, than those in 1805. Although very rapid population increases, especially if it coincides with urbanisation, can cause the ballooning of urban slums and under provision of social services like education and sanitation, the evidence of the last two centuries has shown that our ability to innovate – from new crop types to better sanitation to more equitable institutions – has allowed humankind, again, on average, to flourish.

But one population trend that is attracting more attention is depopulation. Several (rich and not so rich) countries are now recording fertility rates below replacement level, i.e. women are having fewer than 2.1 babies. Some of these countries continue to grow by attracting immigrants. But as the number of countries with below-replacement fertility increases, and the above-replacement fertility rates in other parts of the world continue to fall, immigration might be a zero-sum game. In fact, as the above graph suggests, by 2086, the global population will start to decrease.

Why is that a bad thing, you may ask? One obvious economic consequence of depopulation is the shrinking of the labour force. Japan's population of the working-age group in 2030 is expected to be 92% of its 2020 level, and 68% by 2050, indicating that a serious shortage of labour is inevitable. China, because of a one-child policy in place for 35 years, will soon face the same issue. Schools need teachers, hospitals need nurses, and farms need labourers. Can those jobs really be displaced by robots?

The more serious economic consequences are fiscal: with a smaller population, there will be fewer people paying taxes, reducing government revenue. This can make it more difficult to fund social services and infrastructure and will likely lead to increased government debt. This will be exacerbated by an ageing population requiring more government spending on healthcare, social security, and pensions, further straining government budgets.

Population growth, then, seems like inflation: you do not want too much of it, but you certainly do not want it to be negative either. Consider the following graph from Our World in Data. It plots the fertility rate of eight countries: Bangladesh, Brazil, China, India, Japan, South Africa, Tanzania and the United Kingdom. Six of the eight are now below replacement level. Because there is a delay between birth and death, it takes some time for below-replacement fertility to translate into smaller populations. But for a country like Japan, which has had below-replacement fertility rates since the 1970s, that is now a reality: since the 2010s, the Japanese population has begun to shrink, now by more than 500 000 people annually. China’s fertility rate, despite attempts to boost it, is now even below that of Japan.

South Africa is very much on the right trajectory, with a fertility rate that is just above replacement level. The fear of an exploding population is not an issue in South Africa, as it might be in countries like Tanzania, where fertility rates remain high and mortality rates are in decline. Neither is the fear of depopulation a concern for South Africa, especially since immigration from the rest of Africa is likely to continue.

There are many problems in the country right now. Overpopulation (or depopulation) is not one of them.

An edited version of this article was first published on News24. Photo by Ekaterina Shakharova on Unsplash.

See also 'Factfulness' by Hans Rosling. Sadly Hans has passed but his work is being sustained by his family. Loved this article. Thank you.

Th Simon-Ehrlich wager demonstrating that resource abundance is positively correlated with population radically changed how I think about "donut economics" or "spaceship earth"