How South Africa can medal up

But it will require patience

This is a free post from Our Long Walk, my blog about the economic past, present, and future of South Africa. If you enjoy it and want to support more of my writing, please consider a paid subscription to the twice-weekly posts that include my columns, guest essays, interviews and summaries of the latest relevant research.

South Africa underperforms at the Olympic Games. That has been true since our first participation in St Louis in 1904, when Len Tau, Jan Mashiani and BW Harris ran the marathon, but it has become decidedly worse over the last few decades.

Consider the graph below. It shows the number of gold, silver and bronze medals countries have won at the Games since 1900, each dot representing a medal type for a specific country in a specific year. I’ve used population and GDP per capita statistics, meaning that South Africa moves to the right over the century as our GDP per capita increases. The ‘ZAF’ labels show South Africa’s medals per population for each income level.

There are three obvious things to note. First, the fitted lines reveal that there is an upward trend for medals per population: the richer a country, the more medals per population they win. There is also no difference between gold, silver and bronze medals: richer countries are equally likely to win gold medals as they are to win silver or bronze medals.

The positive correlation between medals and income per capita makes sense: richer countries have more resources to spend on athletes and facilities. They have healthier populations who have the leisure time to train, quality schools, colleges, and universities that can recruit the most talented athletes, sponsorships that pay for coaches and travelling and competitive tournaments that push the best to perform at their best.

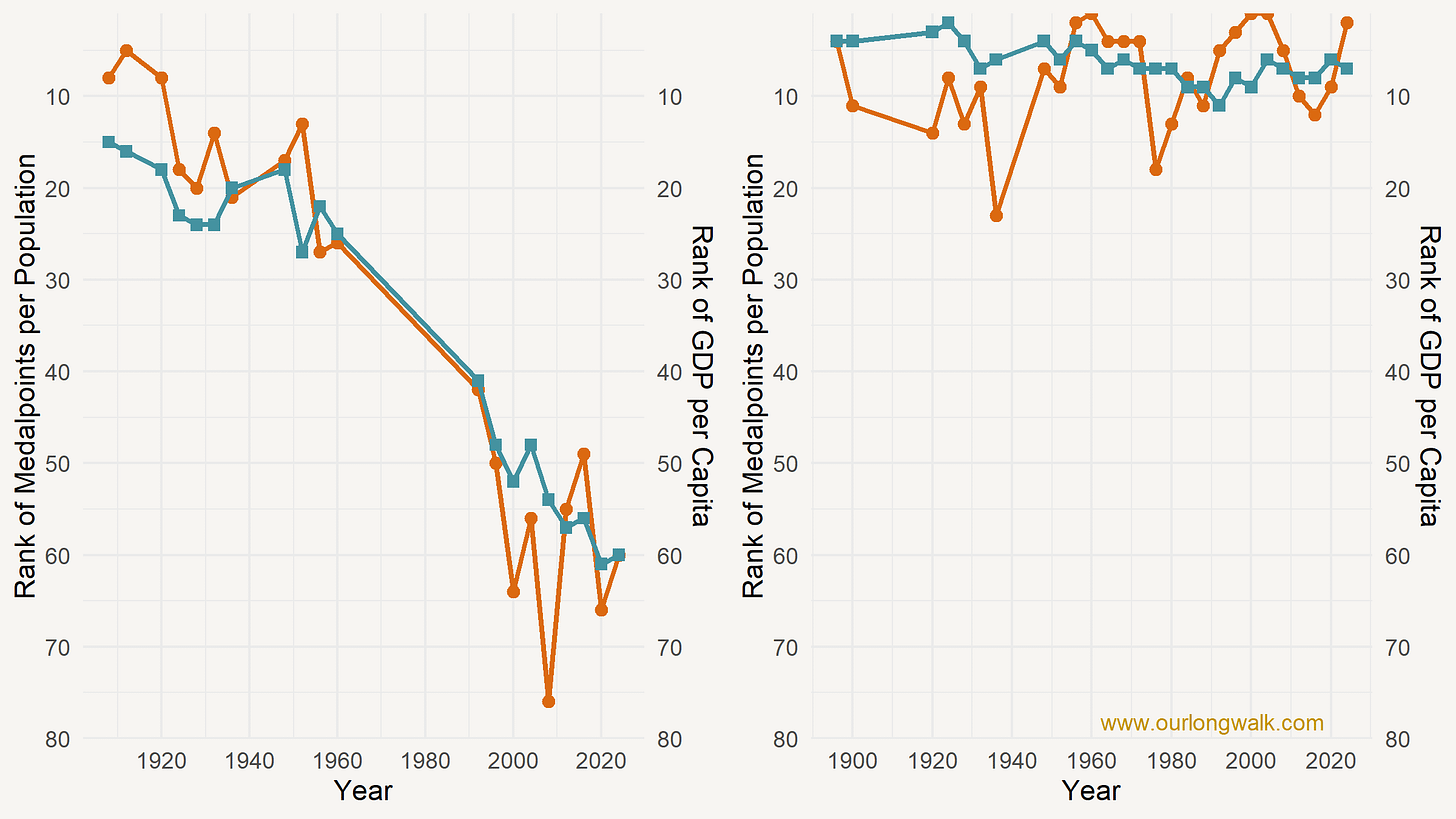

But look carefully at the above graph, and you’ll notice a surprising trend: the higher South Africa’s income per capita (a rightward shift on the x-axis), the poorer our performance. I can demonstrate this another way, by comparing our performance to our perennial archrival: Australia. Below, I first calculate medalpoints (a combination of gold, silver and bronze medals) and rank each country’s performance in each Games based on their medalpoints per capita. I then rank their GDP per capita in the same year, and plot the two lines on top of each other, for South Africa (left) and Australia (right).

Although Australia starts out at a higher GDP per capita rank, South Africa’s Olympic performance is actually initially better. But whereas our GDP per capita ranking falls, and so our Olympic performance, Australia’s GDP per capita stays within the top ten, and so does their Olympic performance.

In short: countries’ Olympic hopes are closely tied to their relative economic prosperity.

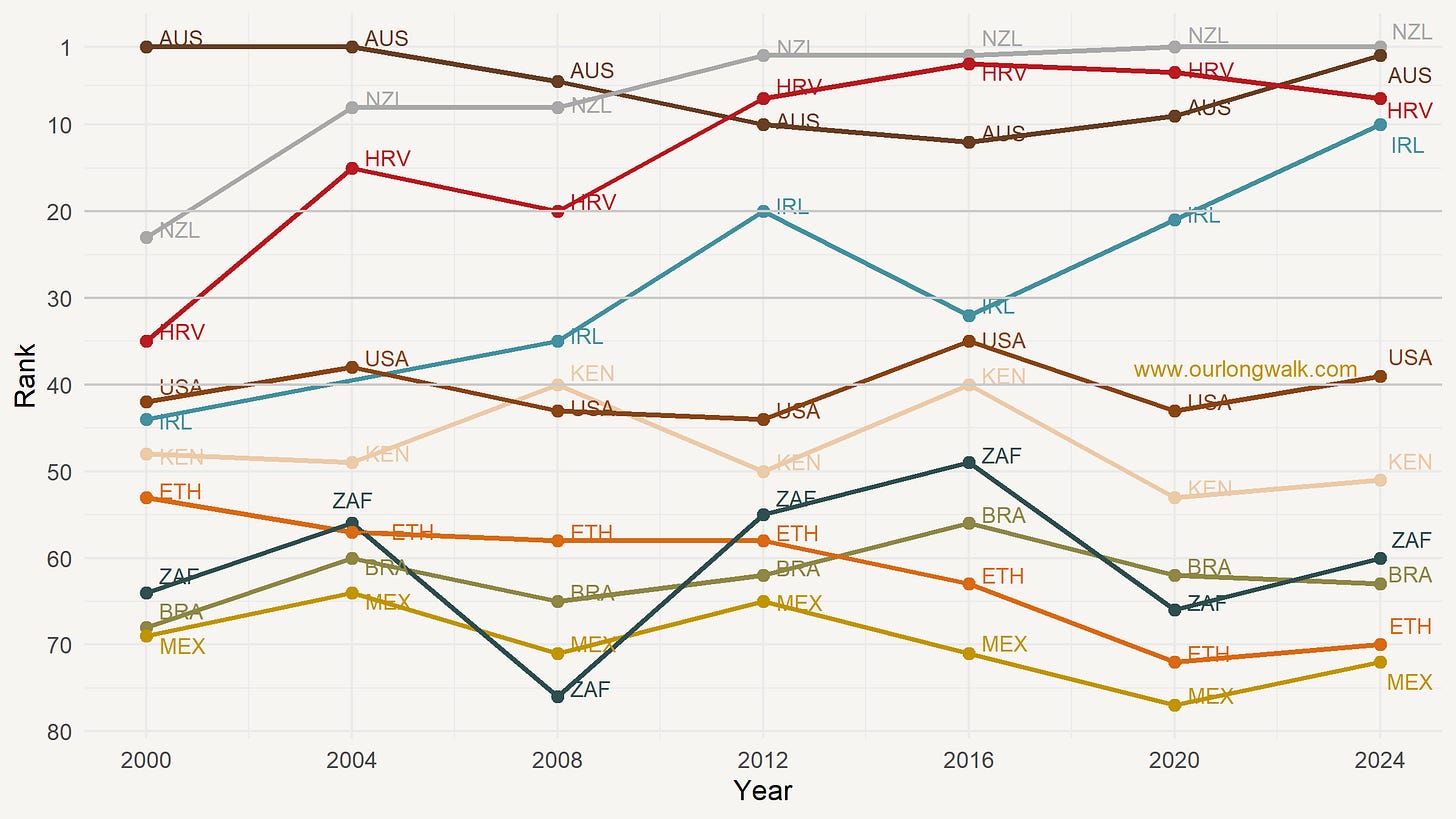

That is not great news if you are the Minister of Sports, Arts, and Culture, hoping to make an immediate impact on South Africa’s medal tally at the Los Angeles Olympic Games in 2028. In fact, in the short run, the best predictor of a country’s medal ranking is their ranking in the previous Olympics. Consider the following graph, which shows the medalpoints ranking of a select number of countries for the last seven Olympic Games. Notice the stability in rankings: lines rarely overlap, meaning that countries mostly maintain their ranking.

Yet there is some movement. Ireland was ranked lower than 40th in 2000 and made the top ten in Paris. New Zealand was outside the top twenty in 2000 and was the best performer in Paris, as I explained here. By contrast, Ethiopia, despite high GDP per capita growth over the last two decades, has been on the decline since 2000. Clearly, there are things that matter besides income per capita.

What those things are is not easy to identify from the data at hand, but one thing is clear: Olympic success starts very early. Bar exceptions like Turkish shooter Yusuf Dikeç, who went viral at the age of 51 for his relaxed, Bond-like demeanour while winning silver, Olympic success is usually the culmination of years of intense training and expert coaching at a young age. Schools and universities are where gold medals are won.

There are thus two approaches. The first, with the short-term aim of winning more medals in LA, is to attract the most promising high school athletes to a high-performance unit and support them there. That requires (government) resources and coordination, both of which are in short supply. Track-and-field and swimming, given South Africa’s history of performance in these two codes, should attract most of our existing public funding.

While this may give us a better chance of at least maintaining our medal tally, it is highly unlikely to shift our medal ranking substantially up. For that, we need a more radical, long-term solution. My proposal: sports schools. There are two ways to do this: get more kids into existing ‘sports schools’ and, secondly, build more of them. In reality, there are only a few dozen schools in South Africa with sports facilities to produce Olympic athletes. (To give an example from rugby: at the end of the 2023 Rugby World Cup, 933 players had represented the Springboks; 40% have come from only 15 of the almost 7000 high schools in South Africa.) Where expensive facilities and equipment are required – swimming, for example, or field hockey – the number of schools with the requisite resources and coaching to nurture the most talented sports stars is shockingly low.

The first proposal, then, is to build more residences at resourced schools for kids with Olympic potential. Stellenbosch High is a great example. The school, in collaboration with the Athletics Cycling Education Trust (ACE Trust) and Endurocad, runs a scholarship programme for talented young athletes from all around the Western Cape. With yearly talent identification clinics and expert coaches, including (1992 Olympic silver medallist) Elana Meyer, Zola Pieterse (Budd), and Ross Tucker, the programme currently supports 50 students, says Deputy Principal Niel Retief, providing them with world-class coaching and training, while also offering a supportive environment to ensure they succeed on the track and in the classroom.

The success has prompted further investment by the ACE Trust. The programme is set to increase its intake to between 80 and 100 students over the next two years. To accommodate this growth, the school is constructing additional infrastructure, including a new residence and dining hall, as well as an international-standard 8-lane tartan track and a state-of-the-art gymnasium. Given these developments, it is not far-fetched to imagine that the next generation of South African track-and-field Olympic medalists will be alumni of Stellenbosch High.

The second proposal would be to build more such schools, turning either existing schools into schools specialisation in specific sports codes, or building new schools from scratch. Specialise. Have schools dedicated to specific sports codes, with specialist coaching to support talented youngsters from across the country who stay in dedicated residences. Imagine Swimming South Africa, Cycling SA or Cricket South Africa (cricket will be an Olympic sport in 2028!) team up with schools to run their own residences and high-performance coaching centres. A school voucher programme – a radical proposal to improve South Africa’s education system – would make this much easier to implement.

At the end of Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom, my book about global economic history, I ask: How do you win the FIFA World Cup? Do you appoint a very expensive coach, which is what South Africa did in 2007 when we appointed Carlos Perreira at R3 million per month? Or do you give every kid in South Africa a soccer ball?

If we give every kid a soccer ball today, we won’t win the World Cup in 2026, nor in 2030 or even 2034. But by 2038, twenty million kids would have played soccer. The best of them would have been selected by local teams, and the best of them purchased by international clubs. At the 2038 World Cup, we’d have a chance.

Winning gold medals at the Olympics requires very much the same investment. We need to give those kids with obvious potential a proverbial soccer ball. That might be a physical ball, but it most likely means a place in a school residence with good nutrition, specialised coaching and a supportive environment. And, for the best of them, an attractive offer, locally or abroad, to further develop their talents in a high-performance environment.

Our medal performance in Los Angeles is unlikely to differ much from Paris. Substantial improvement in our rankings requires not only a fast-growing economy but also a strategic, long-term commitment to nurturing our most talented young athletes. Both will require the patience and stamina of a marathon runner.

An edited version of this article was published on News24. Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. The images were created with Midjourney v6.