How coffee made us rich

And still does

‘When did the Industrial Revolution begin?’ remains the most vexing question in economic history. It is so vexing because it matters so much: if we understand what initiated the transformation of our lives from subsistence farmers to online bloggers, for example, we understand, by implication, the factor(s) that cause economic growth. And, presumably, we could then replicate those lessons everywhere, for the benefit of all.

Schoolbooks today – those that still include the Industrial Revolution in their curriculum, at least – emphasise the eighteenth-century inventions of the spinning jenny and steam engine as the defining features of the Industrial Revolution. (To be fair, I also follow this template in my own Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom.) Others, like the recent Nobel laureates Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, tend to emphasise the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the associated institutional changes that strengthened property rights, limited the power of the monarchy, and created a more accountable government. These reforms, they argue, encouraged investment, technological innovation, and market expansion, laying the groundwork for sustained economic growth.

If only it were so simple. For at least a century, a small school of economic historians have emphasised the seventeenth and even the late sixteenth century as the pivotal period of change. In 1934, for example, the economic historian John Nef pointed to developments in mining, metallurgy and textiles in the early seventeenth century, as well as the dissolution of the monasteries and the expansion of coal mining and glass production in the sixteenth, to suggest a more gradual evolution of industrial capitalism.1 By the 1970s, Fernand Braudel argued that England’s industrial expansion from the late sixteenth century was distinguished by the rapid scaling of industries, surpassing earlier industrial developments in Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands. While key innovations, such as blast furnaces and advanced mining equipment, were imported from more technically advanced regions, England adapted and expanded these techniques on an unprecedented scale. New industries like paper mills, sugar refineries and cannon foundries emerged with larger firms, bigger buildings, and a rapidly growing workforce, marking a shift toward large-scale industrial capitalism long before the conventional Industrial Revolution is thought to have begun.

A new QJE paper – which somehow fails to cite both Nef and Braudel – also pinpoints the dawn of England’s transformation to the seventeenth century. Using new estimates of productivity growth from 1250 to 1870 and sophisticated methods to account for Malthusian dynamics, the authors argue that sustained productivity growth in England began around 1600 – almost a century before the Glorious Revolution and long before the invention of the spinning jenny or locomotive.

Which begs the question: what was it about seventeenth-century England that made the modern world possible?

Here’s my theory: coffee. (And, yes, I am writing this sipping a Plato flat white.)

As Joel Mokyr and various others have argued, the central feature of this period of industrial transformation was the application of new knowledge. Entrepreneurs from all walks of life could experiment with new ideas and innovations, boosting productivity. How this knowledge was shared is an important part of the story. Informal networks such as Freemasonry, friendly societies, libraries, and booksellers played a crucial role, for example. In a 2023 Social Science History paper, the economic historian Gregori Galofré-Vilà shows that counties with higher concentrations of these informal networks experienced greater innovation, as measured by patent activity and participation in the 1851 Crystal Palace World’s Fair. A one-standard-deviation increase in these networks was associated with a significant rise in both new patents and exhibition participation, suggesting a causal link between social connectivity and technological progress.

The British weren’t just inventing – they were inventing strategically. A new NBER working paper by Lukas Rosenberger, Walker Hanlon, and Carl Hallmann shows that British inventors excelled in developing ‘central technologies’ with greater spillover effects, such as steam engines and machine tools, while their French counterparts focused more on peripheral fields like glassmaking and papermaking.

These findings point to the critical role of spaces where ideas could be exchanged freely. Coffeehouses, for example, became hotspots for intellectual exchange, where entrepreneurs, inventors and investors could meet, share ideas, and form collaborations. As Galofré-Vilà explains, these spaces ‘represented the information networks of that time, where people would come in to have a coffee or a drink, share ideas, and get in contact with people from different disciplines’.

Which is why I would time the origin of the Industrial Revolution in England to the arrival of London’s first coffeehouse, established by Pasqua Rosée, in 1652. Located in St Michael's Alley near the Royal Exchange, a key meeting spot for merchants, it began as a modest stall but soon expanded into a permanent space, attracting a diverse clientele of traders, lawyers, and intellectuals. And, once established, the coffeehouse quickly spread. By 1663, there were already 83 coffeehouses across the city, primarily frequented by those involved in trade with the Levant and Baltic regions. And by the early eighteenth century, only fifty years after Pasque Rosée established his first shop, London had around 500-600 coffeehouses, solidifying their role as spaces where ideas, business and news intersected.

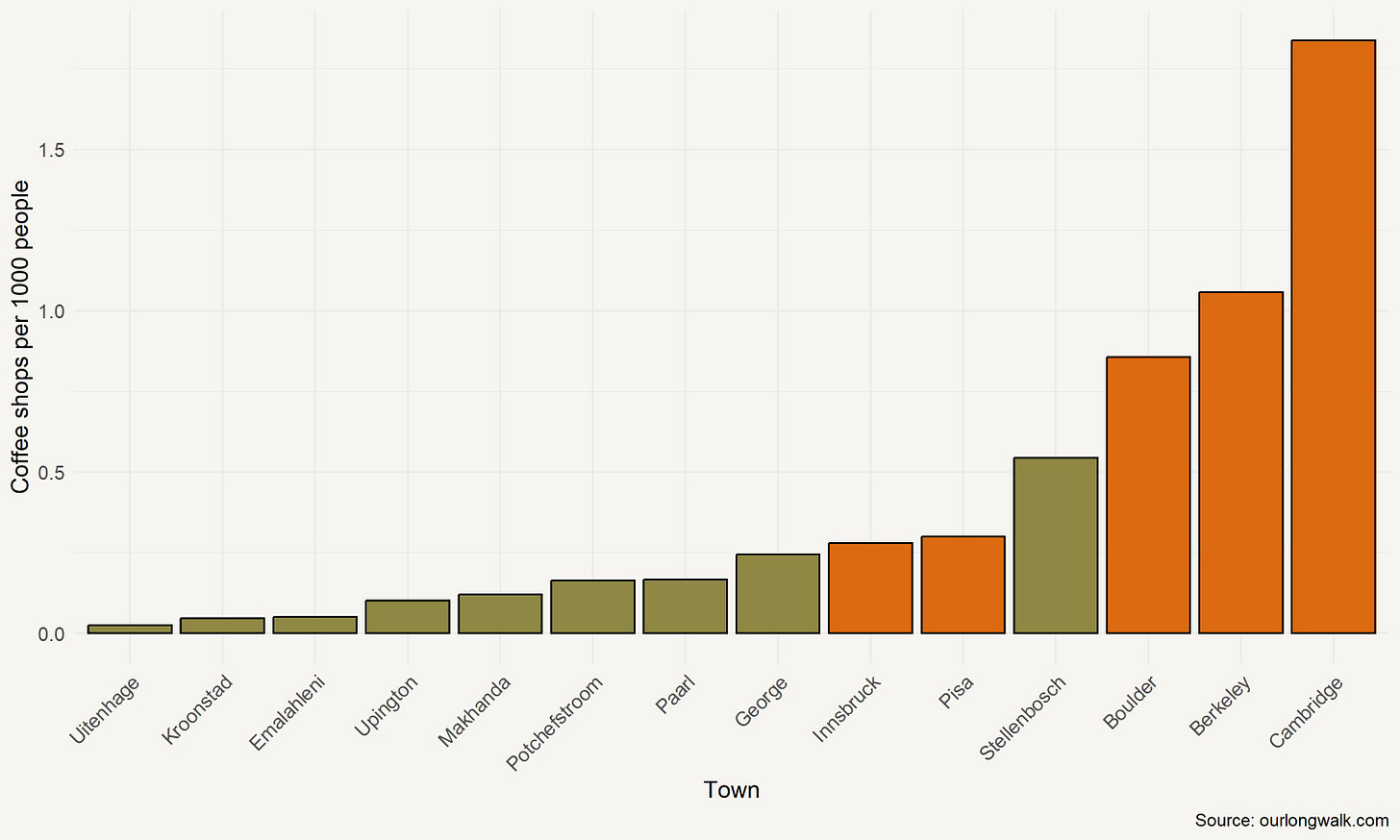

Here’s a provocative claim: coffee is still the lubricant of innovation. To prove2 this, I counted the number of outlets classified as ‘coffeeshops’ in several South African towns (green) and a few international ones (orange). To make them comparable, I only considered towns with between 100,000 and 300,000 people. I then divided that number by the population size to get a coffee shop per capita figure (in this case, per 1,000 people). The figure below shows the results.

The most innovative town in South Africa is Stellenbosch. Yes, Stellenbosch also attracts tourists, but so does George, and it only has half as many coffee shops. Stellenbosch also outperforms a few international cities, like Innsbruck and Pisa. But it performs poorly against the major centres of innovation, places like Berkeley and Cambridge (UK). Perhaps there’s something to be said for Fourie’s coffeeshop-innovation index.

‘It all began in 1652’ is a phrase familiar to many South Africans. Perhaps that year deserves to be remembered not just for its colonial history, but for the founding of London’s first coffeehouse – the kind of place where revolutions, both industrial and intellectual, quietly brewed.

This is an edited and translated version of my monthly column, Agterstories, on Litnet. Special thanks to Kelsey Lemon for valuable research assistance. To support more writing like this, consider subscribing for a paid membership. The images were created using Midjourney.

Thanks to @pseudoerasmus on X for this point.

Just to be clear: this is not a rigorously established causal finding backed by scientific evidence.

Ek weet nie hoekom nie, maar dit laat my hieraan dink: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Detection_Club