Economists as storytellers

Stories can shape not just what people believe, but what eventually becomes true

A big thank you to PSG for inviting me to deliver the keynote at their PSG Advisor Sessions across South Africa – in Gqeberha, Durban, Cape Town, Johannesburg, Polokwane, Pretoria and Bloemfontein – over the past month. The audiences were great. What follows is a condensed version of my talk.

Consider giving a gift subscription to Our Long Walk this Christmas. Friends, family, and the occasional frenemy will get thoughtful reading all year. Set it up in seconds.

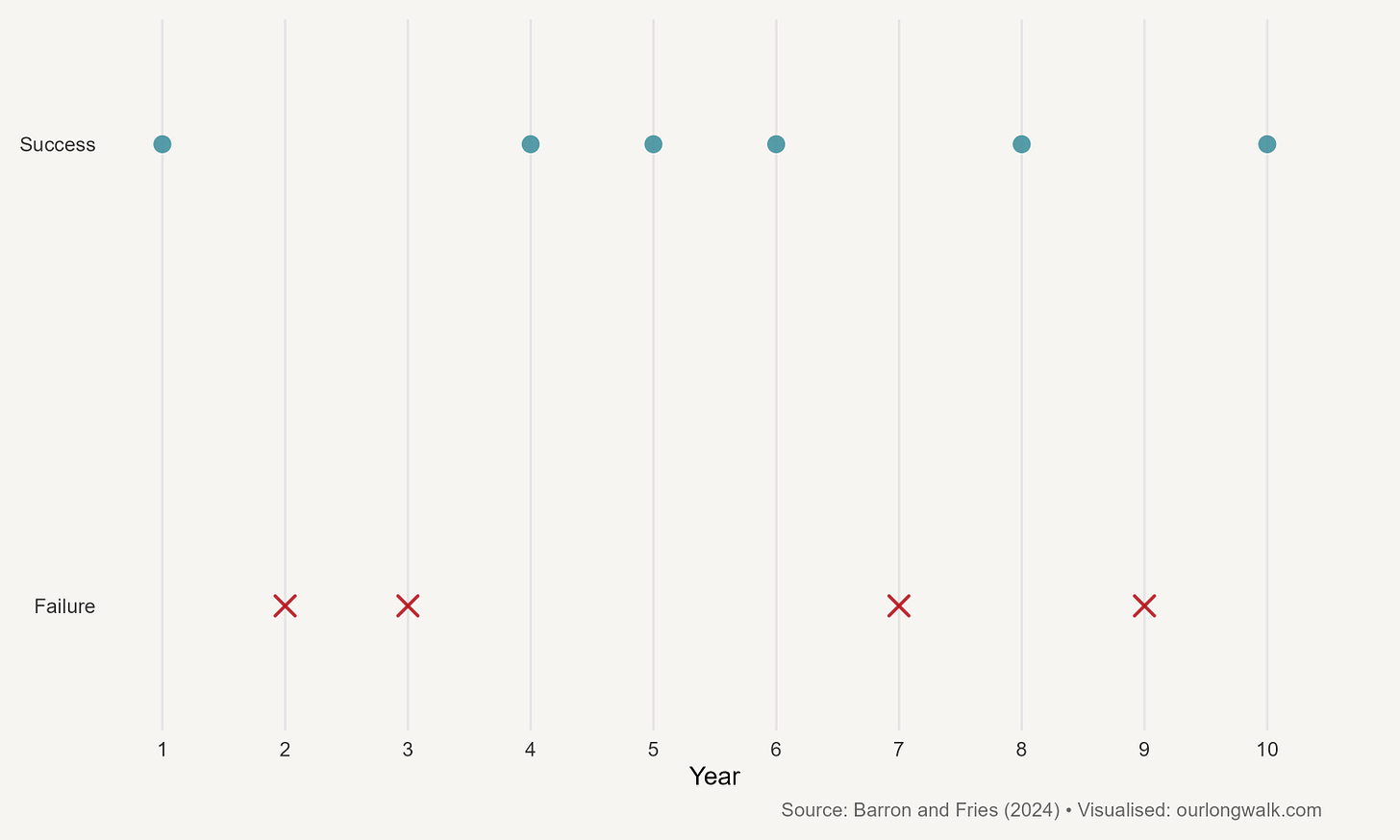

Take a look at the figure below. It shows the performance of a fictional company over several years. Would you invest in it? Some might see signs of a turnaround – a company that stumbled early on but seems to have recovered. Others might focus on the volatility and conclude that it is too risky. The data are identical for everyone, but the story we attach to it shapes what we see.

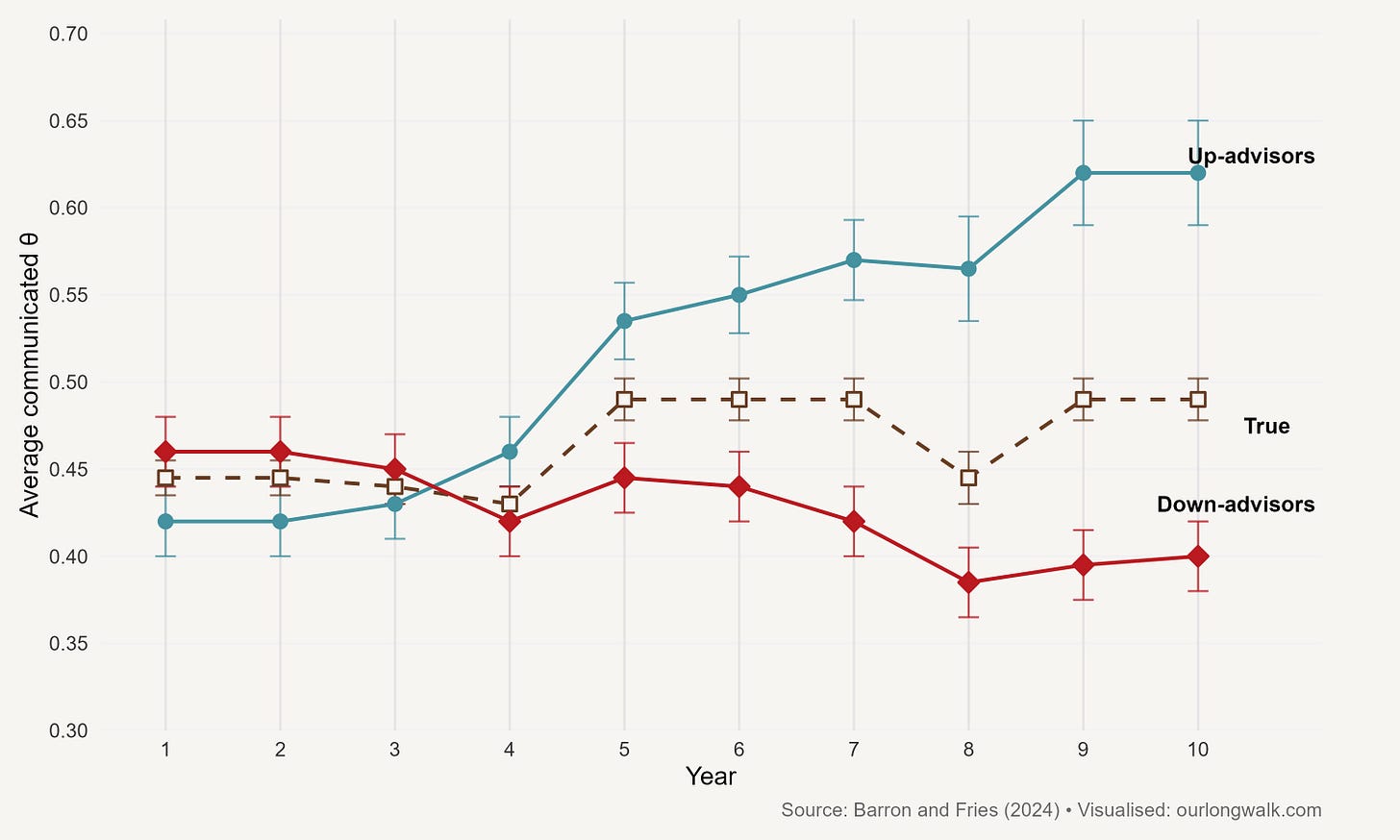

That is what the economists Kai Barron and Tilman Fries set out to test.1 They asked financial advisers to explain identical company data to potential investors. One adviser was told to tell a positive story. She said that a new chief executive had taken over in year three and that this change explained the improvement since then. The investor who heard her version saw a comeback story, a firm rediscovering its footing. Another adviser, asked to be negative, said the opposite: that a new CEO, appointed in year six, meant a decline in fortunes. The data remained unchanged, but the story did not. And so did the decision about whether to invest.

Here’s the kicker: advisors and investors had access to the same information. And yet, investors who heard the optimistic version came away with much rosier expectations about the company’s future than those who heard the pessimistic one. The storytellers had succeeded in shifting beliefs. Those hopeful investors overestimated how well the firm was doing because they had been persuaded by a story that fit the data just well enough to sound right. That was Barron and Fries’s crucial insight. The advisers who were most persuasive were not those who invented the wildest tales, but those who made their narratives feel coherent. They subtly adjusted the timeline of events or changed the emphasis to make the data seem to confirm their interpretation. The conclusion is uncomfortable: give people the same information, and a confident, coherent narrative can still lead them to opposite conclusions.

This tendency to make sense of facts through stories is not confined to investors or advisers. It sits at the heart of how economists themselves work.