Diplomacy begins at home

The G20 summit is Ramaphosa’s chance to prove competence over charisma

Know a business leader who wants evidence-based context on South Africa’s policies? Give them clear, informed pieces twice-weekly throughout 2026. Gift an Our Long Walk subscription this Christmas.

Trump recently said that South Africa does not belong in the G20. To some extent, he’s right. Consider the graph below. South Africa is the third-poorest G20 country on the list (shown in the triangles, measured on the y-axis). Only India and Indonesia are poorer on a per-capita basis. Yet Indonesia has more than four times South Africa’s population. India has more than twenty-two times.

We’re there because we represent Africa (even though the African Union is now also a member). We’re also there because of a historical quirk. Sometime in 1999, Timothy Geithner, then deputy to US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, was on the phone to Germany’s secretary of state for finance, Caio Koch-Weser. The two each had a list of countries along with their GDP, population and trade data. As Robert Wade writes, ‘They proceeded down the list, ticking some countries and crossing others: Canada in, Spain out, South Africa in, Nigeria and Egypt out, Argentina in, Colombia out...’.1 And so, the story goes, this was how the membership of the G20 (Group of Twenty) was decided.

The concept of global summitry – the idea that a coalition of the world’s ‘systemically important’ nations, would help steer international governance – emerged in the 1960s with the founding of the G10.2 The size and membership of these fora have always been contentious. Over the years, the various G-meetings have run the gamut: from the ungainly G77 (now home to 134 developing countries) to the tight coalition of G7 representing the most economically powerful nations. The tiniest of which, the G2 (America and China), was resuscitated by Trump just last month.

The G20 was the brainchild of Larry Summers and Canada’s former prime minister, Paul Martin. In the wake of the 1990s financial crisis, they saw the need for a larger, more representative forum to foster global financial stability and cooperation. It was to be a group, as Adam Tooze writes in Crashed, that could be more representative than the Bretton Woods twins of the World Bank and IMF, but not so large as to be unmanageable, like the UN. For the Americans, Wade notes, this enlarged coalition held the added benefit of diluting the group’s Europeanness, at the same time as it incorporated US allies like Australia, Argentina, Saudi Arabia and South Korea. In its original formulation, the G20 comprised finance ministers and central bank governors who met for the first time in Berlin in December 1999.

As the immediate threat of the financial crisis receded, however, the fervour behind the G20 died down. In the intervening years, states sent successively less senior representatives. Paul Martin, who had always envisioned the G20 as a leadership summit, nevertheless persisted. It would take another financial crisis, the global financial crisis of 2008, for Martin’s dream G20 to be realised. On 22 October 2008, George W Bush invited the most senior leaders of each G20 member nation to meet in Washington DC for the first G20 leaders (or G20L) summit.

It was at this precise moment that South Africa was on its strongest international footing in the democratic era: growth had averaged 5% between 2004 and 2007; debt was below 30% of GDP; we were investment-grade across the board; inflation targeting had proved its worth; the rand was strong; and the 2010 World Cup loomed as evidence that the state could still deliver. If you were building a crisis-management ‘steering committee’ for the world and needed a single African country at the table, South Africa was the obvious choice.

We’ve remained influential partly because of our president. Cyril Ramaphosa has been the continent’s foremost diplomat: chairing the African Union, brokering ceasefires, leading vaccine diplomacy during the pandemic, and keeping South Africa on cordial terms with all sides in a polarised world. He is a dealmaker by instinct and a negotiator by training.

Yet I want to suggest that diplomacy is not what South Africa should prioritise as it hosts the G20 summit this month in Johannesburg. Rather than projecting global gravitas, the GNU would do well to use the event to sell South Africa as an investment destination.

That won’t be easy. Johannesburg is not exactly a symbol of success. The Wall Street Journal recently published an article ‘Welcome to Johannesburg. This Is What It Looks Like When a City Gives Up.’ That headline stings because it’s true. Yet potholes can mean two things. They can signal collapse. But they can also signal opportunity, especially if investors are given reason to believe that the rules that govern are sound, and the inputs that depend on the state – electricity, ports, low inflation – are becoming more reliable, as businessman Adi Enthoven recently noted at a Stellenbosch University talk.

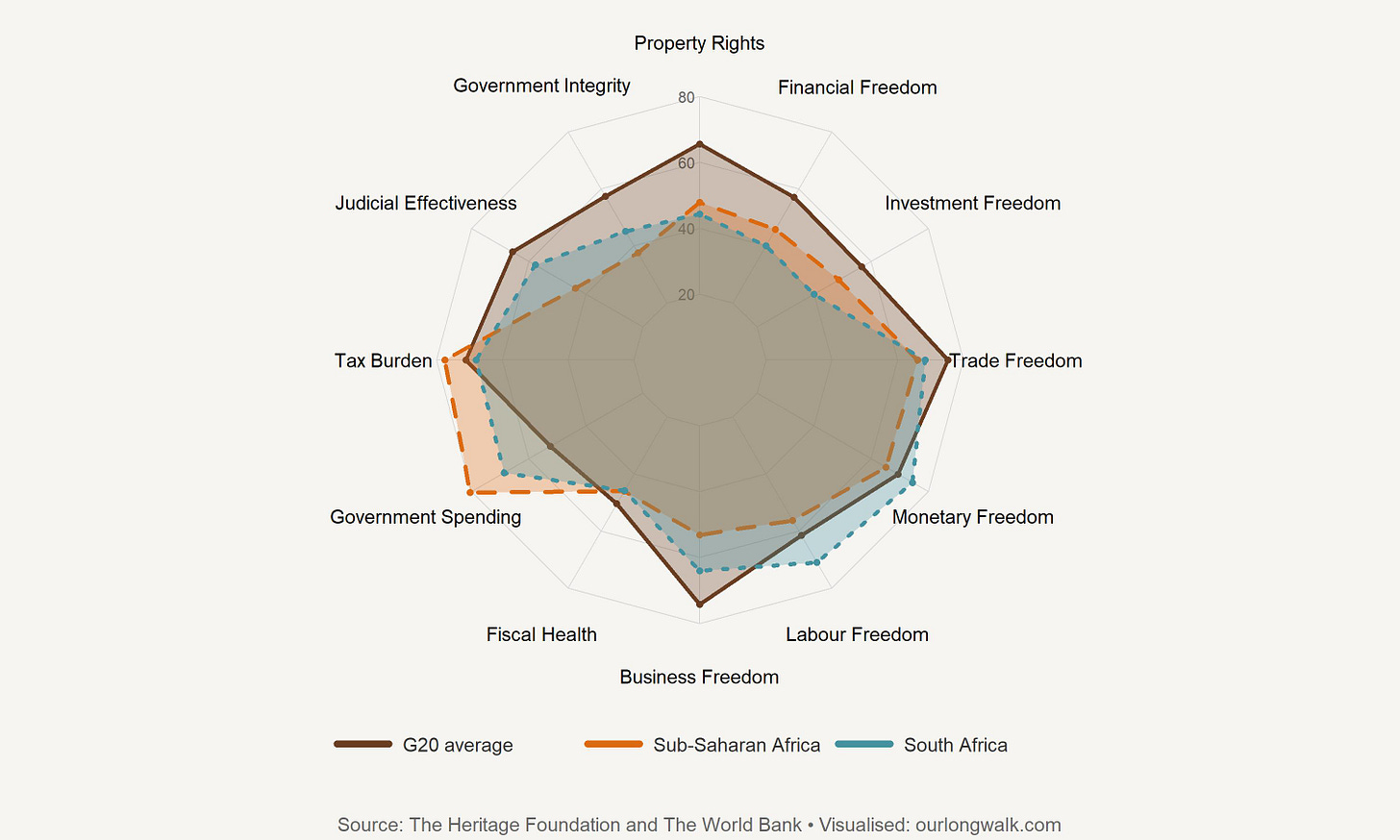

But more can – and should – be done to make South Africa even more attractive. The Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom measures how countries protect property, enable enterprise, and limit government interference. (For those who suspect ideological bias: note that the United States itself has fallen sharply in the rankings since Trump’s tariffs.) The graph compares South Africa’s scores with the G20 and sub-Saharan averages. It shows a familiar pattern. South Africa performs well on labour and monetary freedom. But we fare far worse in the areas that matter most for capital formation: investment freedom, business freedom, financial freedom, and property rights.

These are the foundations of growth. Property rights, for instance, are not merely about owning land; they are about the confidence that contracts will be honoured, titles registered, and permits enforced. For investors, predictability is everything. Endless debate over expropriation without compensation, even when it leads nowhere legislatively, creates a fog of uncertainty. The slow digitisation of the deeds office, the glacial pace of mining and water licences, and an erratic approach to enforcement all reinforce the impression of an economy where rules are negotiable.

Business freedom suffers from the same malaise. South Africa’s entrepreneurs face a bureaucracy designed for a richer state than the one we have. Each permit, inspection and application consumes scarce administrative capacity. The consequence is a system that simultaneously over-regulates and under-delivers. Operation Vulindlela has shown what is possible: the spectrum auction, the liberalisation of private power generation, the reform of water-use licences. Yet the backlog of small, unnecessary regulations still dwarfs the progress.

The same logic applies to financial and investment freedom. South Africa’s financial system is sophisticated, but its regulatory architecture is layered and inconsistent. Exchange-control reforms have been piecemeal. Investors, foreign and domestic alike, price that uncertainty. Add to this a decade of shifting localisation targets, protectionist trade measures, and intermittent hostility toward private finance, and it is little wonder that investment spending hovers near its lowest level in two decades. The irony is that South Africa’s balance sheet – sound banks, deep capital markets, and a freely floating currency – ought to be a comparative advantage. Instead, the constant threat of policy reversal erodes trust.

This summit, then, should be treated not as a stage for diplomacy but as an investment roadshow disguised as a global meeting. The government could use it to announce tangible progress: the finalisation of the transmission-system operator, new port and rail concessions, and a functioning e-visa regime for skilled workers. Just last week, Minister of Finance Enoch Godongwana announced two additional proposals I had on this list: a lower inflation target and a national procurement dashboard that lets the public see every contract awarded. That was a smart move.

But most importantly, a more sensible approach to black economic empowerment – one that rewards new investment, innovation and job creation rather than ownership reshuffles – would send a powerful signal. So would the creation of public digital infrastructure: open, interoperable platforms for payments, data and logistics that lower costs for entrepreneurs and make the state legible again. And a serious commitment to improving the investigative capacity of the police – ensuring that wrongdoing, from top to bottom, is uncovered and prosecuted without fear or favour – would restore faith that South Africa’s institutions still have teeth. Each of these is precisely the kind of credibility-building step that signals a state ready to govern by rules rather than relationships.

Will potholes in Johannesburg disappear overnight? No. But investors will forgive potholes if the rules are clear and future policies are more predictable. Do those things and we will grow; grow and our per-capita ranking among G20 peers will steadily lift; lift and even Mr Trump’s provocation will lose its sting. If we want to prove we belong in this club, the way is not grandstanding on the global stage. It is for Ramaphosa – and the government he leads – to turn diplomatic skill from convening others to coordinating a domestic consensus for growth.

An edited version of this article was published on News24. Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. The image was created with Midjourney v7.

Robert H. Wade, ‘Emerging World Order? From Multipolarity to Multilateralism in the G20, the World Bank, and the IMF’, Politics & Society 39, no. 3 (2011): 354.

Juha Jokela, ‘The G-20: A Pathway to Effective Multilateralism?’ Chaillot Papers: Institute for Security Studies, European Union, 2011

Fascinating. I remember you touching on the fluidity of global power structures in your piece last month. It's wild to think G20 membership was almost an algorythm of who was on a list the year I was born. Makes you wonder about the long-term impact of such quirks, even if SA does represent a continent.

I think the 2 approaches (international diplomacy vs investment roadshow) may actually be closely linked.

A couple of months ago, through a very random series of events, I had a very interesting conversation with a European diplomat. He was touring the country securing some investment opportunities for the country he represented. The version of South Africa he spoke about was very very different from that we read in the news everyday. He also mentioned that since there is so much uncertainty around the USA, many European countries have been looking to South Africa to diversify.

The South African market may be too small for the returns many European companies may be looking for. But if it continues its mission as a "Gateway to Africa" from 20 or so years ago (or even much longer if one considers Rhodes' vision), this may be attractive. If there are enough South African companies that can facilitate transactions (e.g. Standard Bank, ABSA, etc), logistics, etc, making South Africa a critical launchpad to a much bigger market. But for that to happen, there needs to be a degree of "soft power", both within African countries and to the rest of the world, where South Africa can be perceived as some kind of "leader" within the continent, and its companies having the capability and access to markets wider than home. And I think that's where the diplomacy comes in. If the "South Africa" name is frequently mentioned in global circles, that positioning is strengthened. I'm a regular reader of the Financial Times, and for a couple of weeks earlier this year, South Africa was regularly mentioned (not always good things ofcourse). Therefore, I think it's working.

Also, tnere is so much more to Johannesburg that potholes :D. I even forgot we had them until reading this post and noticing one or two again.