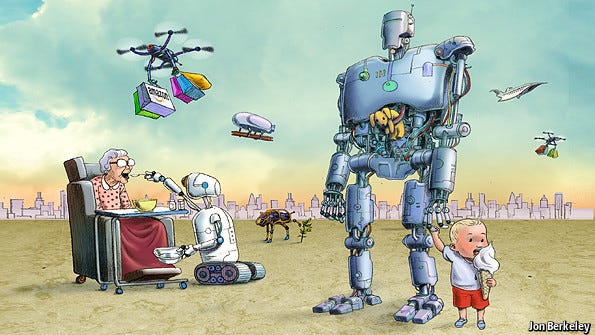

Will robots cause massive unemployment?

At least a quarter of all South African men and women of working age that are willing and able to work are unable to find a job. Unemployment is the scourge of our times, depriving households from incomes that will allow them to buy the goods and services that will, by increasing their consumption of nutritious food, sending their kids to good schools, giving them access to health services, ensuring safe and secure homes for their families, and providing ample opportunities for leisure activities, improve their living standards. The psychological scars of joblessness can be severe and persistent too. Few would deny that, in an ideal world, all citizens who are able and willing to work can find a job and provide for their families.

And yet, there are deepening concerns that technological progress is stealthily eradicating the need for human labour. With the emergence of artificial intelligence, robotics, the Internet of Things, autonomous vehicles, 3-D printing, nanotechnology, biotechnology, materials science, energy storage, and quantum computing in everyday applications, a very real social problem seems to be on the horizon: Will the firm of the future have any need for human workers? And given the poor quality of skills in South Africa due to Bantu Education and the failure of the post-apartheid government to improve the performance of black schools, is it not plausible to expect that South Africa’s unemployment rate will soon rise to 50%?

South Africa is not alone in confronting this immense societal challenge. The economic consequences of the Rise of the Robots – also known as the Fourth Industrial Revolution – were the main topic of discussion at the World Economic Forum at Davos in January, with great fanfare but little content. A far better analysis, instead, is provided by MIT economist David Autor in a paper published in the December issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives. In ‘Why Are There Still So Many Jobs?’, Autor asks why automation has not wiped out most jobs over the last few decades, as it was predicted to in the 1960s.

The simple answer is that automation both substitutes and complements human labour. Yes, automation (machines, robots, algorithms) replaces labour. Walk into any car manufacturer and the dearth of technicians and labourers – especially compared to 50 years ago – are striking. But automation also complements labour, increasing productivity and earnings, which augments the demand for labour.

Think about bank ATMs. A new study by Boston University professor James Bessen shows that ATMs quadrupled in the US from 100 000 to 400 000 between 1995 and 2010. One might assume that the spread of ATMs replaced the need for bank tellers, but as Bessen shows, bank teller employment actually rose from 500 000 to 550 000. Why is this? ATMs reduced the cost of operating a bank branch (by substituting what more expensive bank tellers do). Because of this cost reduction, however, banks opened many more branches across the US, and could thus employ more bank tellers (although fewer tellers per branch). And because ATMs could now do the menial task of cash-dispensing, bank tellers were freed up to offer other types of ‘relationship banking’ services, introducing clients to new banking services like credit cards, loans and investment products.

The effect of automation on employment thus depends on whether workers’ tasks are substituted or complemented by automation, whether there are enough workers in the economy to respond to the greater demand for the complementary tasks, and what those new workers prefer to do with their incomes. Let’s use another example: Farmers are increasingly using GPS navigation equipment to automate harvesting, substituting the need to employ (experienced) tractor drivers. Can these tractor drivers adjust their skills to complement the new automation? Probably not, which means that their jobs as tractor drivers will be replaced by technicians able to install and run GPS navigation software. If there are fewer such technicians available (which there are), it is likely that their wages will be higher than what the experienced tractor drivers earned. But these technicians will in all likelihood also spend their incomes on products and services different from the tractor drivers, benefiting industries unrelated to the GPS automation (like restaurants and golf clubs) and hurting others (the local spaza shop).

The latter is often an overlooked point. Many fear that automation will replace unskilled labour for highly skilled jobs. This is indeed true in the first stage of the story: the tractor drivers losing their jobs to GPS technicians. But the higher farm productivity pushes both the incomes of the farmer and the technicians to higher levels, allowing them to spend in the rest of the economy – and often on services where automation has less of an effect. Such services often employ unskilled labour intensively, like restaurant waiters or greenskeepers. Automation could thus have a net positive impact on unskilled labour.

Empirical evidence seems to support this hypothesis. Autor reports that automation in the US and Europe seems to have had a positive impact on high-paying and low-paying jobs. But, surprisingly, it is the middle-paying occupations – like office clerks, building trade workers, machine operators – that have lost out. He calls this phenomenon the polarisation of employment.

I find it unlikely that automation will result in significantly higher unemployment in South Africa. Automation will result in higher levels of productivity, increasing the incomes for those with the skills to complement the rise of the robots. Their higher incomes will likely be spent on services where unskilled labour is intensively used. Expect the demand for occupations as disparate as cleaners, security guards, health-workers and hairdressers to increase – those jobs where automation can is complementary to human labour.

Because of the large supply of unskilled labour in South Africa though, such greater demand will reduce unemployment but is unlikely to affect wages. Unless we can open our borders to skilled migrants, inequality between the incomes of the top with its small pool of skilled workers and the large pool of employed but low-wage earners will thus increase further.

Those currently employed in back-office jobs where creativity and human interaction is not required should be warned: the robots and algorithms are coming for your job. My advice: Find a way to build or programme the robots, or analyse the data they generate. Or choose a service industry where automation will complement those very human tasks of creativity, imagination and human interaction.

*A shortened version of this first appeared in Finweek of 18 February. Image source: Jon Berkeley, The Economist.