Will rhinos survive?

Only if economists intervene

In my wedding speech many moons ago, I read a letter written by my imaginary grandchild in 2061 for Helanya and my 50th wedding anniversary. It went something like this:

Grandma always tells the story of how her grandpa (my great-great-grandfather!) was a wildlife expert. And how her father used to take them to the Kruger National Park every year, searching for the Big Five—the lion, the rhino, the elephant, the leopard, and the buffalo. I wish I too could still see a living rhino.

That imaginary future is increasingly plausible. In 2011, the year of our wedding, there were more than 11,000 white rhinos in the Kruger National Park. By 2024, fewer than 2,000 remained. We are losing these animals at an alarming rate, largely due to poaching fueled by growing demand for rhino horn and ivory in global markets.

Yet, there is reason for cautious optimism.

A study published recently in Science by Timothy Kuiper and colleagues presents one promising strategy: proactively removing rhino horns, known as dehorning. The idea is straightforward. Without horns, rhinos become far less attractive targets for poachers. Kuiper’s team analysed data from 11 Southern African reserves over six years, finding that proactive dehorning reduced poaching by an impressive 78%, despite using only about 1.2% of the conservation budget. In stark contrast, traditional anti-poaching methods, including ranger patrols, detection dogs, and camera systems, showed little measurable effect on poaching rates, despite consuming a far larger share of conservation resources.

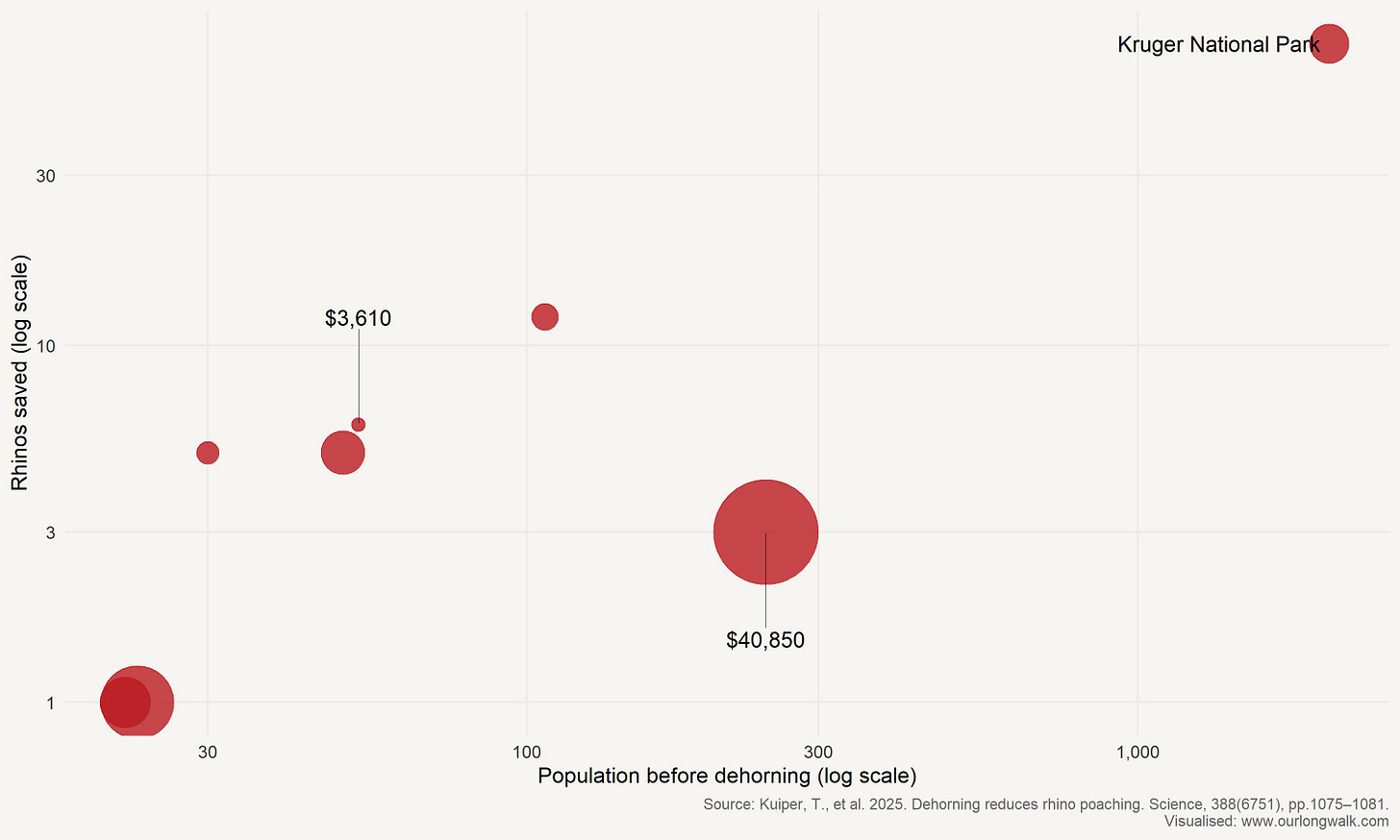

Yet even within these encouraging results, many issues remain. For instance, Kuiper’s study also revealed considerable variation in the cost-effectiveness of dehorning across different reserves. The accompanying graph illustrates these differences clearly: some smaller reserves managed to save rhinos relatively cheaply, while larger reserves, like the Kruger National Park, incurred significantly higher costs per rhino saved. This variability highlights how much we still have to learn about implementing dehorning effectively.

This raises an intriguing question: what role does economics play in wildlife conservation? A traditional economic view sees wildlife conservation as a simple problem of supply and demand. On the supply side, policy options include increasing anti-poaching patrols and surveillance to reduce illegal horn availability, proactively removing rhino horns (dehorning) to make poaching less rewarding, or producing synthetic rhino horn as an alternative. On the demand side, policymakers might focus on education campaigns to change consumer preferences and reduce horn consumption, or impose heavier penalties to deter buyers from purchasing illegal products. Another, more controversial option involves legalising the rhino horn trade, allowing regulated markets to operate openly and potentially driving down prices to undercut illegal traders. In 2013, Duan Biggs and his co-authors argued in the journal Science that legalising rhino horn trade could reduce prices, undercutting poachers’ profits. Their logic was simple: sustainably harvested, legal horn could compete against illegal horn by being cheaper, safer, and more ethical.

However, economic theory rarely translates neatly into reality, especially when dealing with complex and illegal markets. Solomon Hsiang and Nitin Sekar illustrated this in a provocative 2016 NBER working paper. They investigated the effects of a one-time legal sale of ivory stockpiles to China and Japan, concluding that rather than reducing poaching, this sale unexpectedly increased it. Their analysis suggested that the legal sale might have inadvertently legitimised ivory, widened its consumer base, and made smuggling easier, illustrating how policies based on straightforward supply-and-demand theory can sometimes backfire.

Surely that is the end of the legalisation debate, then? Not quite. The findings by Hsiang and Sekar have been subject to extensive debate and remain unpublished in any peer-reviewed academic journal. One reason for this controversy, highlighted by Fiona Underwood, involves significant methodological concerns. Underwood explains that Hsiang and Sekar’s analysis overlooks the variability in the number of elephant carcasses discovered at different sites. Because these numbers can differ dramatically– from sites with just a few carcasses to those with hundreds – the method used by Hsiang and Sekar may inadvertently overstate certain trends or produce misleading results. By ignoring these differences and treating all sites equally, their analysis introduces biases that could significantly influence the conclusions drawn. Underwood’s alternative analysis, which takes these measurement complexities into account, finds no clear evidence of the sharp increase in poaching claimed by Hsiang and Sekar.

Similar uncertainty surrounds the idea of synthetic rhino horn. Frederick Chen, in an article published in Ecological Economics, argues that introducing synthetic horn, indistinguishable from real horn, might actually backfire. If synthetic horn producers compete by promoting their product as superior, they might inadvertently raise the overall price and encourage more poaching. Interestingly, Chen proposes an alternative strategy: deliberately producing synthetic horns that are indistinguishable but slightly less appealing to consumers. These ‘inferior fakes’ could suppress demand and thus reduce poaching pressure, illustrating just how nuanced economic approaches to conservation need to be.

However, ideas such as Chen’s are notoriously difficult to test in practice, as real-world evidence from carefully controlled experiments is scarce. This scarcity of evidence makes organisations like CITES – which adopt cautious, conservative stances – unlikely to embrace radical, untested interventions like synthetic horn strategies anytime soon. But we can gain important insights from natural experiments, which occur when real-world events create situations resembling controlled tests.

One recent example comes from Emma Gjerdseth’s recent study published in World Development. Gjerdseth analysed the impact of a common conservation tactic: publicly destroying confiscated ivory stockpiles to signal that ivory has no legitimate value. Her empirical research, spanning many African countries, delivered surprising results. Contrary to intentions, these destruction events did not deter elephant poaching. Instead, they appeared to increase it. Economically, this result makes sense: destroying ivory publicly signals its growing scarcity, inadvertently driving up its black-market price and encouraging even more poaching. Intervening in markets without careful consideration of incentives carries significant risks of unintended consequences.

In June, the Peace Parks Foundation moved 10 critically endangered black rhinos from South Africa to Mozambique’s Zinave National Park, restoring a population lost for fifty years. It is a remarkable achievement. Yet these rhinos, like so many others, have been dehorned for their own safety, a clear sign of the tough trade-offs that define both economics and conservation. If we are to save both the rhino and its horn, we need to experiment more, testing regulated legal trade and exploring synthetic alternatives. We also need more economists to study these issues, rigorously test and evaluate each approach, and work closely alongside ecologists and wildlife managers. Only then can we ensure that my grandchildren, and yours, will one day see a rhino, with its horn intact, roaming freely in the wild.

This is an edited and translated version of my monthly column, Agterstories, on Litnet. To support more writing like this, consider signing up for a paid membership. The image was created using Midjourney. Audio created with ElevenLabs.

Again, Johan, it is delightful to see economics/economic thinking applied to everyday issues of concern and within the understanding of the general public. A lot of people shy away from economics since a lot of consentration on economic theory alone is not everyone's cup of tea! Of course in academia and among academics, high theory is inevitably and absolutely essential. Yet it is always for me as an economist myself quite delightful to read "economics made digestable" for non-economists. Thanks for doing it ...