Why growth matters for South Africa

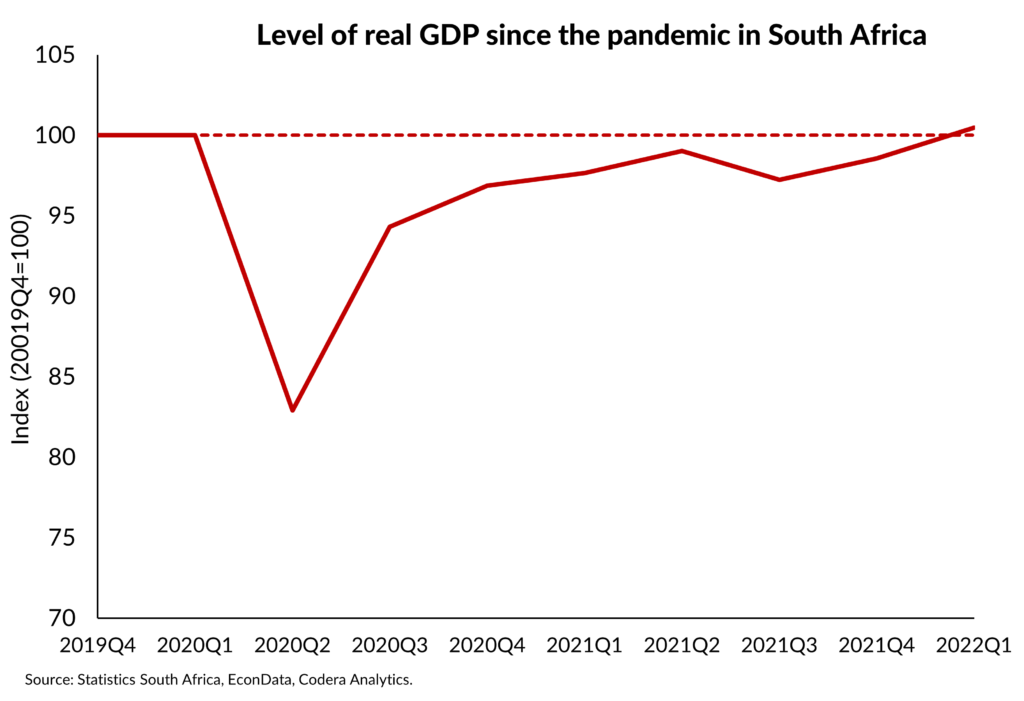

South Africa’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a measure of a country’s economic performance, is back to its pre-Covid level. On Tuesday, Statistics South Africa announced that real GDP was 0.5% above its level before Covid-19 and the associated lockdowns that brought production and trade to an almost standstill.

For a country that had experienced such a remarkable decline in output in 2020 – a fall of more than 7%, the worst since 1920 – to achieve this rapid turnaround is pretty remarkable. In fact, South Africa has never before produced as much as it has in the last quarter. Many analysists, myself included, thought it would take at least three to five years to return to pre-Covid levels. And add all the other challenges businesses have faced – continued Covid waves, loadshedding, protests and floods, and most recently, rapidly rising fuel prices – and this achievement looks even more remarkable.

A sectoral breakdown helps to show that not everyone is back to normal. Construction is way down, 25% less than in 2019. In comparison, agriculture is up by more than 35%, benefiting from few restrictions during lockdown and other favourable conditions. My sense is that fundamental shifts during the pandemic has also helped to shift some into a higher gear. Sure, we benefited from the tailwind of high commodity prices. But work-from-home trends have lifted productivity for those in the services sectors too. Flexible work hours have meant that traffic has eased, saving time, money and frustration. Closed international borders have meant more local spending – although the decline in tourism is still evident in the GDP figures. And it should be said that there are headwinds – inflation, for example – that might derail this progress.

Yet what these figures also reveal is the power of exponential growth. GDP is a flawed number, but it is the best we have to measure one thing we all care about: how much value is created that lifts our incomes and raise our standards of living. There are several voices who lambast economists and governments for using GDP: they note that other things we also deeply care about, like leisure time or the environment, are excluded from it. True, GDP cannot capture everything of value, but what these critics forget is that GDP is correlated with almost all things we care about. Just compare the quality of environmental services, like biodiversity, between rich and poor countries. Or the amount of hours and the quality of leisure of people in rich countries to those in poor countries. Rich countries can pay for the protection of their environment and for taking time off work. In Sweden, for example, your salary increases when you take leave!

Although GDP is not perfect, it is remarkably powerful. One way to understand this is through the Rule of 72. Divide 72 by any growth rate and you will get the number of years it will take a society’s income to double. At a 1% annual economic growth rate, for example, it will take 72 years for income to double. (What does it mean for income to double? It basically means that your salary would be double what it is now with prices remaining the same.) At a 2% annual growth rate, still not very impressive, the number of years needed for income to double falls to 36. At 3%, it falls further to 24. You get the story. At a whopping 6% annual growth rate, everyone in society would double their income every 12 years.

The figure demonstrates just how powerful this exponential growth is. On the left side is an index, with 5000 in 2022. Let’s assume this is $5000, roughly South Africa’s average income per person (GDP per capita) today. If South Africa’s economy is only growing at 1% annually, then by 2072, fifty years from now, we won’t even have doubled our GDP per capita. South Africa would still be a middle-income country, roughly as rich as Argentina or Turkey is today. However, were we to grow at 3% per annum – as we have done at an annualised rate in the previous quarter – then our average incomes would double every 24 years; by 2072, then, our income will be four times larger, or roughly equivalent to Portugal’s income per capita today. Were we to grow at only 1 percentage point more over the next 50 years, at 4% per annum, our incomes would increase by a factor of 6. We would be richer than Italy today or almost as rich as France. Finally, if we miraculously grow at 6% per annum for the next 50 years, then by 2072, the average South African will have higher living standards than the average Swiss today. While no country in history has grown at 6% for 50 years, making it a somewhat implausible thought experiment, several have achieved such high percentages for shorter time periods. The point is: even if we could ‘only’ reach 3% for the next 20 years, the South Africa of 2050 would be a remarkably different country than the one today.

The truth is that South Africans cannot prosper without economic growth. Sure, we can debate the type of value creation we would want to see – do we, for example, want more coal-fired power plants or more solar panels – but, ultimately, we need to produce more goods and supply more services. More production raises incomes which reduces poverty and drives social mobility. It also boosts tax revenues which pays for the things we care about most, like clean air or public transport or Swedish holiday subsidies. To argue that GDP should be ignored is to argue for a life of continued poverty and misery.

The StatsSA news of an annualised 3% growth rate is therefore something worth celebrating. But having achieved it in one quarter is no promise that we will remain there. Many challenges can pull growth back. Doing the necessary to address these should be the priority of those in charge of building a better life for all.

* An edited version of this first appeared on News24. All data is supplied by Codera Analytics. Photo by Anurag Yadav on Unsplash.