We are still on the way up

I arrived in the USA a day after Donald Trump was announced as president-elect of the United States. I gave talks at Harvard, Mount Holyoke College and MIT, and met with several faculty and students over the four days of my visit. It was eerie. Some students were still in denial, not helped by the fact that they started drinking as soon as the results became evident. Others were in various stages of grief: angry at the nativism of a large chunk of Americans, bargaining in the hope that Hillary might still win, or depressed at how quickly the America of Obama – to whom many at these prestigious institutions look up to as an inspiring intellectual – has given way to the America of Trump – whom they consider to be a coarse, boastful buffoon.

Trump’s victory seems to have been another nail in the coffin of liberty and progress. In America, walls will replace bridges. Despite what Trump has said on the campaign trail, his tax cuts will likely benefit the wealthy elite. And his views on women, on LGBT rights, on climate change, on health care, on trade openness and on immigration is likely to reverse much of the gains in general freedoms the US has made over the last decade.

These trends are not limited to America. Earlier this year the Brexit result revealed the same nativist fear, an anti-open, anti-globalisation vote. Brexit was a vote for a return to the ‘good old times’, however unlikely that is to materialise. It was a vote against intellectualism; liberal London against the conservative hinterland. And in South Africa, the rise of nativist populism on both the extreme right and left reflect a similar frustration with the progressive Rainbow Nation of yesteryear and its liberal (sell-out!) constitution.

Across the globe, it seems, the extraordinary liberty and progress of the 1990s and 2000s are being rejected for a more insular, protectionist conservatism.

We should not be that surprised. Liberty and progress, as a historian at MIT reminded me on my recent visit, is never a foregone conclusion, never an obvious eventuality. Liberty and Progress is not an Uber ride, taking the shortest, fastest route to a known destination. It is, as the Beatles knew, a long and winding road. Sometimes there are detours, and sometimes we get lost.

Take, for example, Martin Plaut’s latest book, Promise and Despair, the story of the delegation of black leaders that traveled to London in 1909 to fight for representation in the new Union of South Africa. Remember, since 1853, the Cape Colony had had a non-racial franchise, allowing men of all races who had sufficient income or property to vote. When the unification of South Africa began to be discussed following the Anglo-Boer War, many had assumed that the (Liberal) English government would extend the same franchise to all. In fact, this was the promise Lord Salisbury had made in 1899. But politics trumped morals. To secure the support of whites in South Africa in case of war, the English reneged on their promises and turned down the appeal of the delegation. Liberty and progress had to wait.

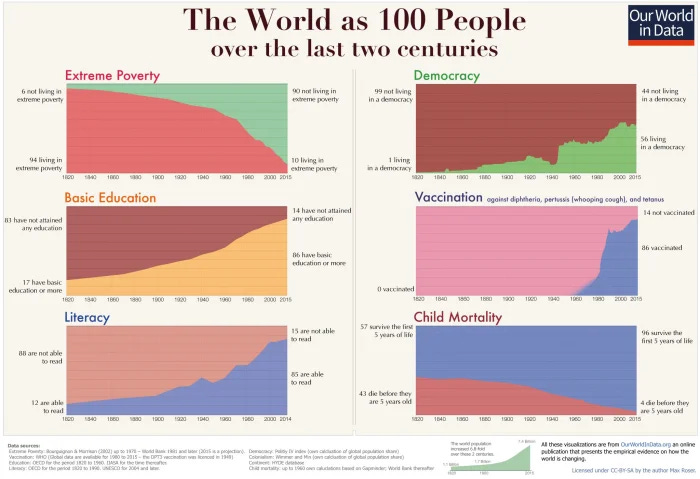

But to focus on the newsworthy failures of liberty and progress the last few months misses the much bigger story of the last few decades: the incredible improvement in living standards of most of humanity. Johan Norberg, in a new book simply titled Progress, concurs: ‘Despite what we hear on the news and from many authorities, the great story of our era is that we are witnessing the greatest improvement in global living standards ever to take place.’ Life expectancy has risen sharply, poverty and malnutrition have fallen. The risk of death in war or natural disaster is tiny in comparison to our parents or grandparents.

Reasons to be optimistic: Trends for important human welfare measures are all positive in the long run. Source: ourworldindata.org

But this does not mean we should be complacent. Says Norberg: ‘There is a real risk of a nativist backlash. When we don’t see the progress we have made, we begin to search for scapegoats for the problems that remain. Sometimes it seems that we are willing to try our luck with any demagogue who tells us that he or she has quick, simple solutions to make our nation great again, whether it be nationalizing the economy, blocking foreign imports or throwing the immigrants out. If we think we don’t have anything to lose in doing so, it’s because we have a bad memory.’

2016 has been a year of setbacks. It reminds us that liberty and progress are never fait accompli, never self-evident. We have to work hard at it, and even then it is not guaranteed. It requires patience and a long-term view. But don’t let 2016 shake your beliefs about humanity’s march forward: we are still on the way up, even if it will take us a little longer to get there.

*An edited version of this first appeared in Finweek magazine of 15 December. Image source: TIME.