Vibe shift

Is the South African economy finally moving in the right direction?

Rudolf Gouws died last week. He was a South African economist, an artist, and one of the earliest supporters of Our Long Walk. He combined a sharp analytical mind with a storyteller’s instinct – with words, with numbers, and with the sensibilities of someone who paid close attention to the world. I dedicate this post – which I suspect he would have enjoyed – to his memory.

Scroll through LinkedIn these days and you might think South Africa has invented a new national sport: good-news posting. My feed is crowded with images of building plans: new office towers, apartment blocks and boutique hotels – often in Cape Town but increasingly elsewhere too. Mixed in are stories of South Africans packing up in London, Amsterdam or Dubai and coming home. Even government officials, from the Minister of Home Affairs to the Mayor of Cape Town, now share short clips about faster visas and cleaner vistas. Add Netflix’s documentary about the ‘Minister of Enjoyment’, and you start to feel that something has shifted.

Inside boardrooms the mood has shifted too. Investors who, not long ago, were looking for the exits now talk about fresh capital flowing in. Open The Open Letter and you scroll through page after page of start-ups selling software, services and schemes to fix everyday South African problems – the small, experimental firms that usually precede a more dynamic economy. Over the last few weeks South Africa has also been on the world stage, not because something has gone wrong but because we are chairing the most important economic club on the planet. The Cabinet even announced last week that it was considering a bid for the Olympic Games, the kind of ambition that would have been hard to take seriously in the era of Stage 6 loadshedding.

It is not just me thinking there is a vibe shift. At the beginning of the month, business leader Adi Enthoven, in a Stellenbosch lecture, asked whether, after ten years of decline, South Africa has turned the corner. His answer – that the trajectory has shifted from negative to positive, especially in energy, logistics and water – has been widely shared, precisely because it captures the emerging mood in business circles. And, while the eyes of the world are on us, last week President Ramaphosa wrote his weekly letter under the headline ‘The green shoots of an economic recovery’, listing falling unemployment, an improving fiscus, an S&P upgrade and progress on Operation Vulindlela. (My News24 column the week before had urged him to do exactly this, although I am fairly sure correlation should not be confused with causation.)

The obvious question for a skeptical reader, and for any serious investor, is whether that vibe has content or whether we are just high on Springbok (and, dare I say, Protea and Bafana) victories.

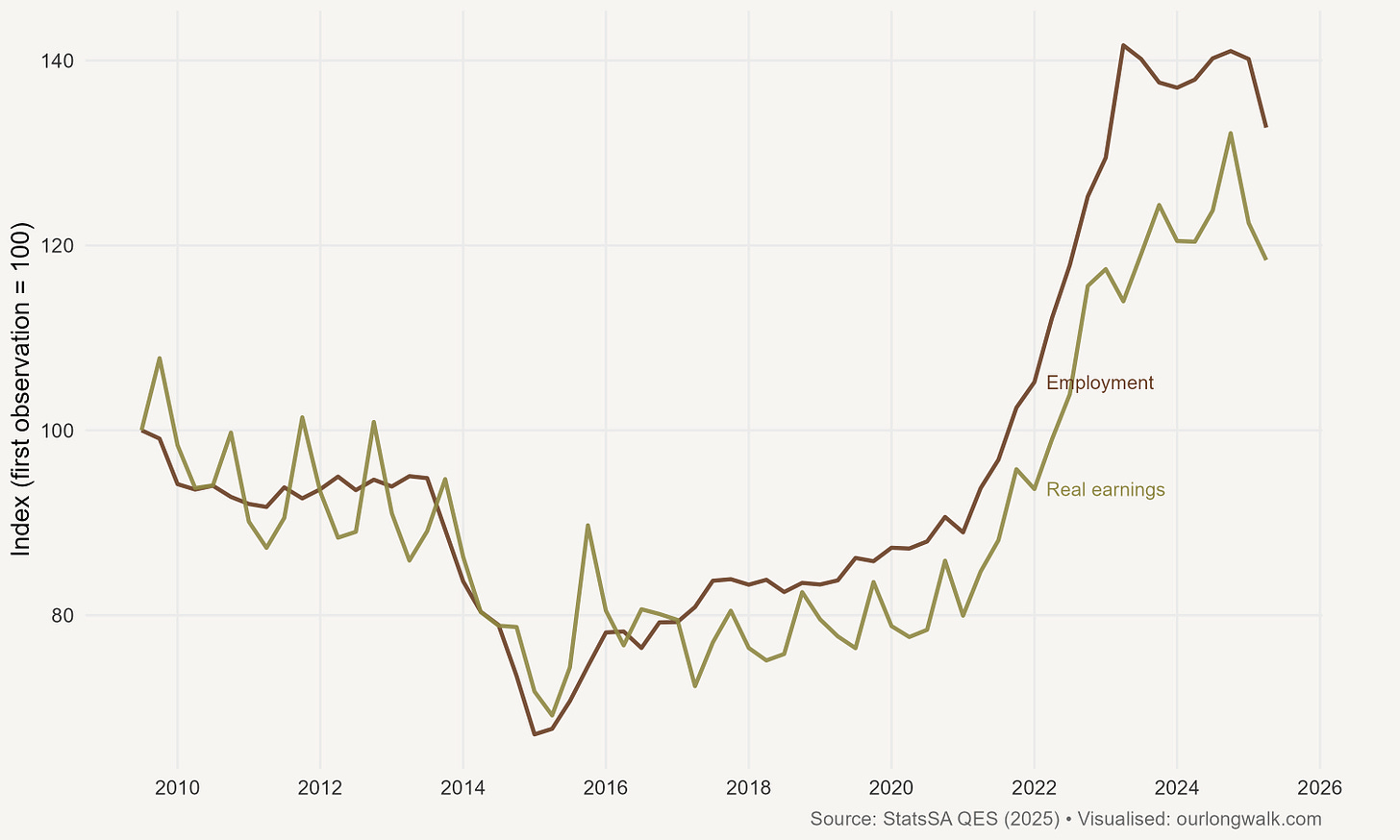

I’ll start with the core of economic progress: innovation. The graph below shows real earnings and employment in research and development in the formal private services sector, roughly 20,000 VAT-registered firms in finance, insurance, real estate and business services. Through the mid-2010s both lines were drifting down. Since around 2022 they have turned decisively upwards. Real earnings in R&D-intensive firms are at record highs; employment has almost doubled from roughly 15,000 to close to 30,000. In other words, more South Africans are now paid to think, design and experiment than at any point in our history. That is not a short-term cyclical story; it is the slow rebuilding of an innovation base.

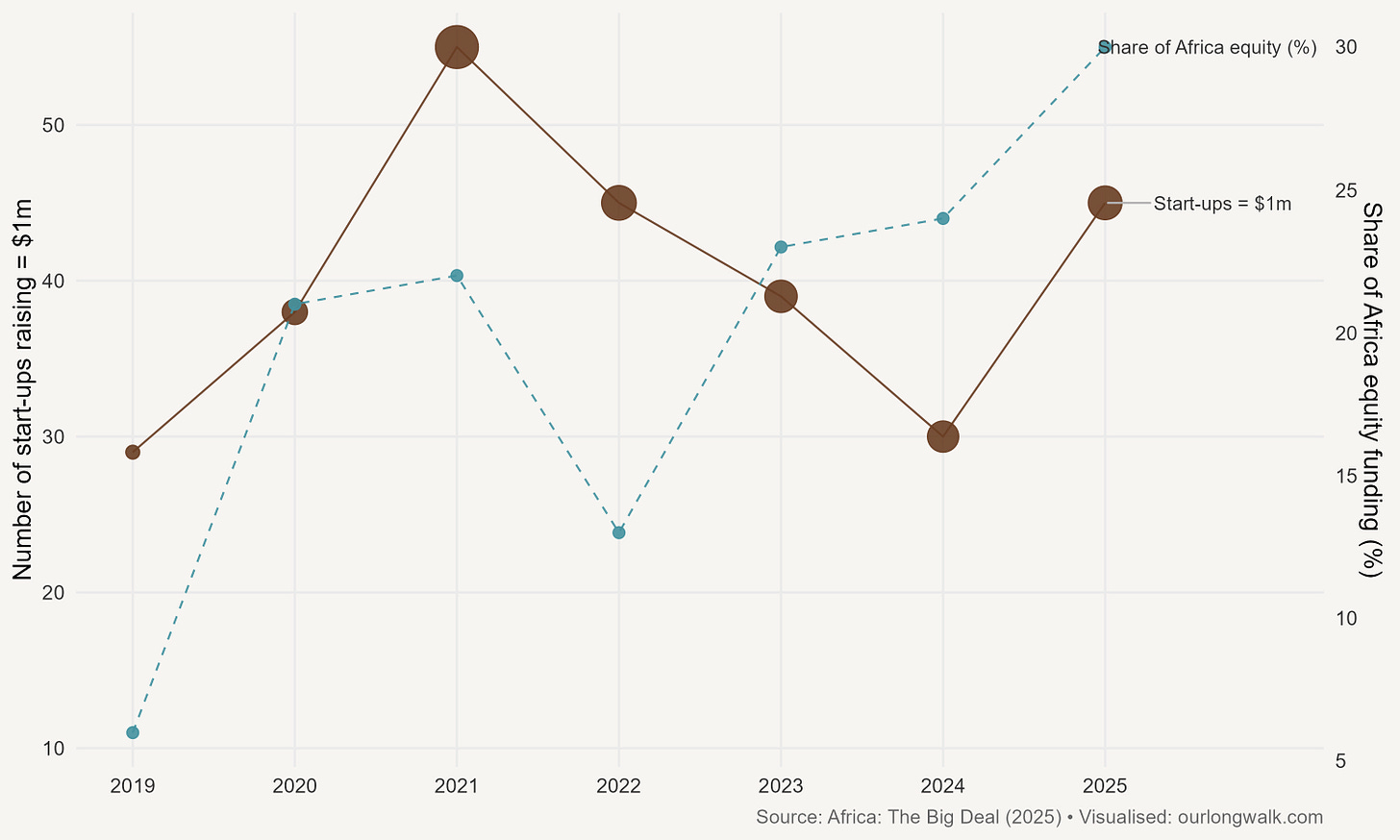

Risk capital is telling the same story. Venture funding data show that South Africa has become the continent’s leading market for equity funding. As Africa: The Big Deal reports, measured by total funding, we have always sat in the ‘Big Four’ with Nigeria, Kenya and Egypt. But since 2023, South Africa has attracted the largest share of equity deals in Africa. So far this year, South Africa constitutes about 30 per cent of all equity raised on the continent (see graph below); start-ups here have raised around $449 million in equity, more than in 2023 and 2024. South African firms dominate in healthcare, media and entertainment, and deep-tech; we are second only to Nigeria in fintech. There have been more exits here than in any other African country, from Nedbank’s acquisition of iKhokha to Lesaka’s deal for Bank Zero. This is not the profile of an economy investors are writing off.

Enthoven’s lecture helps to connect these micro stories with the big structural shifts. He reminds us just how bad the 2014–23 decade was: a 30 per cent loss of earlier gains in per capita GDP, collapsing network industries, and a public debt ratio heading towards 80 per cent. Then he documents the reforms that followed the 2019 Treasury paper and the launch of Operation Vulindlela: the end of loadshedding through a combination of better Eskom management, criminal prosecutions, original-equipment-manufacturer contracts and a rooftop-solar boom; the unbundling of the National Transmission Company and the Electricity Regulation Amendment Act, which together create a genuinely competitive power market; a private-sector pipeline of roughly 16 gigawatts of new generation already registered with the regulator and many more gigawatts in various stages of environmental approval; sharp improvements at key ports and the opening of freight-rail slots to private operators; clearance of the water-licence backlog; spectrum auctions, visa reform and the gradual professionalisation of the civil service. You can argue about the speed and completeness of each of these, but it is difficult to maintain that nothing has changed.

The macro numbers are beginning to catch up. We are on track for a third consecutive primary budget surplus. S&P Global has upgraded South Africa’s foreign-currency rating to BB and the local-currency rating to BB+, with a positive outlook. It explicitly cites Eskom’s improved performance, stronger tax collection, lower diesel spending and structural reforms that have ‘picked up pace’. The Treasury’s debt profile, while still heavy, is no longer on an obviously explosive path.

Financial markets have been quickest to price in the shift. Since the start of the year the JSE is up by roughly a third, with much of the gain driven at first by technology and precious-metal counters, but more recently by the steady re-rating of solid, domestically focused firms such as the big banks, retailers and insurers. The rand has strengthened about 9% against the dollar, new listings are beginning to appear again on the JSE’s boards, and South African equity indices in dollars have outperformed both the MSCI Emerging Markets and MSCI World since the formation of the Government of National Unity – not the behaviour of investors who think the country is circling the drain.

These headline stories hide changes in the supposedly boring parts of the real economy. Agriculture, for instance, is in the midst of another strong season. Wandile Sihlobo reports that the 2025–26 winter wheat crop is forecast at just over 2 million tonnes, about 5 per cent higher than last year, with particularly strong harvests expected in the Northern Cape, Free State, Eastern Cape and Limpopo. Wheat imports will still be necessary, but they should be lower than in 2024–25, and world supplies are ample.

Tourism, a major employer of relatively low-skilled workers, is recovering strongly. Statistics South Africa’s July figures show that income from accommodation was up 10,4 per cent year-on-year, with hotels up 18,3 per cent. That is not only pent-up demand after Covid; it is a sign that foreign and domestic visitors again trust the country’s logistics and hospitality systems.

Even PRASA, long written off as irredeemable, has numbers worth reading twice. Passenger trips rose from 4,48 million in April 2024 to 7,65 million in March 2025. On-time performance is reported at 91 per cent, cancellations at 3 per cent, and 35 of 40 lines are back in operation. This is far from Swiss precision, and anyone who has used the system will have their own caveats, but it is a genuine reversal from the near collapse of a few years ago.

None of this is to say that all is good and well. Unemployment at 31,9 per cent, even after the recent fall and the additional 250,000 jobs in the third quarter, is still socially catastrophic. Business and consumer confidence in the BER surveys remain stuck near the bottom of their historical ranges. Real GDP growth is projected at around 1 to 1,5 per cent over the next few years, which is not enough to dent poverty meaningfully. And many serious issues require urgent attention: violent crime, organised extortion, collapsing municipalities, and a regulatory thicket that often punishes smaller firms more than it disciplines large incumbents. Enthoven is blunt on this point too, calling organised crime the new face of state capture and pointing to local government and the professionalisation of the civil service as make-or-break tests for the reform agenda.

A vibe shift is not a substitute for growth. But it does matter, because expectations shape investment, and investment shapes the future data. The question is whether we can turn sentiment and early reforms into a self-reinforcing cycle rather than another false dawn.

This is where the G20 comes back in. For the first time, the leaders of the world’s major economies gathered on African soil this past weekend. The declaration they published speaks the language of interdependence, stressing that individual nations cannot thrive in isolation and committing to solidarity, equality and sustainability as pillars of inclusive growth. Strip away the diplomatic prose, and several elements matter directly for South Africa’s investment case: a commitment to mobilise finance for just energy transitions; a stronger partnership with Africa aimed at crowding in private capital; and a focus on digital infrastructure, data governance and artificial intelligence that dovetails with South Africa’s strengths in fintech, telecoms and research.

Ramaphosa’s G20 letter picks up the same theme, arguing that ‘we are able to showcase a country and an economy on the rise’. For once, the sales pitch is not wildly out of sync with the underlying numbers. An S&P upgrade with a positive outlook, rising venture funding, the rebuilding of R&D capacity, and the slow but visible repair of Eskom and the logistics system all point in the same direction as the G20 declaration itself. For a country that needs confidence as much as it needs capital, that alignment between domestic reform and global appetite matters.

What is clear is that there is a genuine change in momentum. But, as in sport, momentum is fragile. It takes a long time to build and one bad spell to lose. The risk is not that South Africa is faking a recovery, but that we underestimate how quickly it could be knocked off course by a Government of National Unity that forgets why it exists. The data suggest that, for now, the country has wrestled momentum away from the pessimists; the task for the GNU is straightforward but difficult: keep reform moving, clear out the criminal ecosystems, fix local government – and make sure that, in ten years’ time, the good-news posts clogging your LinkedIn feed feel less like an anomaly and more like how South Africa normally works.

‘Vibe shift’ was first published on Our Long Walk. The images were created with Midjourney v7.

It's nice to have good news about Africa. Anywhere Africa. Thanks for this.

Dit is high time vir 'n bietjie positiwiteit in die land