This will be a BAD year

On bees, trees and the diligent donkey

My least favourite numbers are 6 and 2, so ‘26 is destined to be an annus horribilis. (Given that my two favourite numbers are 3 and 1, I only have to wait a few more years for the best decade. By the way: I also like 4, and have no particular qualms with 5, 7, 8 and 9.)

But I’m also a grown-up man who knows that favourite numbers are like imaginary friends. So I’ve done the obviously grown-up clickbait thing and created an animal acronym for the things I believe will define 2026. This, I believe, will be a BAD year: the year of the Bee, the Acacia tree and the Donkey.

Bees

Bees are, among other things, remarkable energy managers. A bee colony does not rely on a single store of energy or a central controller. Individual bees carry small amounts of nectar. The hive stores honey as a buffer. And when conditions chang, the colony reallocates effort quickly, cooling the hive, shifting foraging patterns, or, in extreme cases, abandoning the hive altogether and rebuilding elsewhere. African honeybees are particularly good at this. Evolved in hot, volatile environments, they prioritise resilience over permanence, favouring distributed storage and rapid adjustment rather than stability at all costs.

That, increasingly, is how modern energy systems are beginning to look.

In 2024, the economics commentator Noah Smith republished a 2022 post about why batteries would be the technology of the decade. That original post appeared just months before the release of ChatGPT and the boom in generative AI. In his 2024 preamble, Smith wrote:

In light of the sudden efflorescence [of AI], the humble battery might seem quaint and prosaic, and my post might seem laughably mistimed.

And yet two years later, I think my post still holds up. These two years have seen small battery-powered drones utterly change the way wars are fought. They have seen battery storage become a common complement to solar, solving almost all of solar’s intermittency problem and drawing huge amounts of investment worldwide. Batteries have powered the sudden meteoric rise of China’s car industry, which went from an also-ran to a juggernaut that suddenly threatens to dominate the entire global auto market. AI is certainly magical and holds incredible potential, but in just a couple of years, batteries have begun to transform human energy supply, war, transportation, and geopolitical dominance.

Also, it’s quickly becoming apparent that AI and batteries are, in many ways, perfectly complementary technologies. Drones are human-piloted now, but autonomous AI-operated drone swarms are coming, and they are going to change war and the balance of power yet again. AI promises to turn robotics from a niche type of machine tool into a ubiquitous feature of our world. The rise of autonomous machines will be – must be – battery-powered.

Another two years on, and it is fair to say that Smith was on to something. Have a look at the drone show China put on over the festive period. And for those of us who live in regions with serious fire risk, drones are now how you fight fires in China.

But Smith does not quite do justice to what cheap batteries could mean for the poorest. The continent I call home is energy poor. The comparative politics scholar Ken Opalo wrote an excellent summary of just how important it is to focus on electricity generation if we are to reduce Africa’s high poverty rates. Many others have echoed that view. What is still underappreciated is storage.

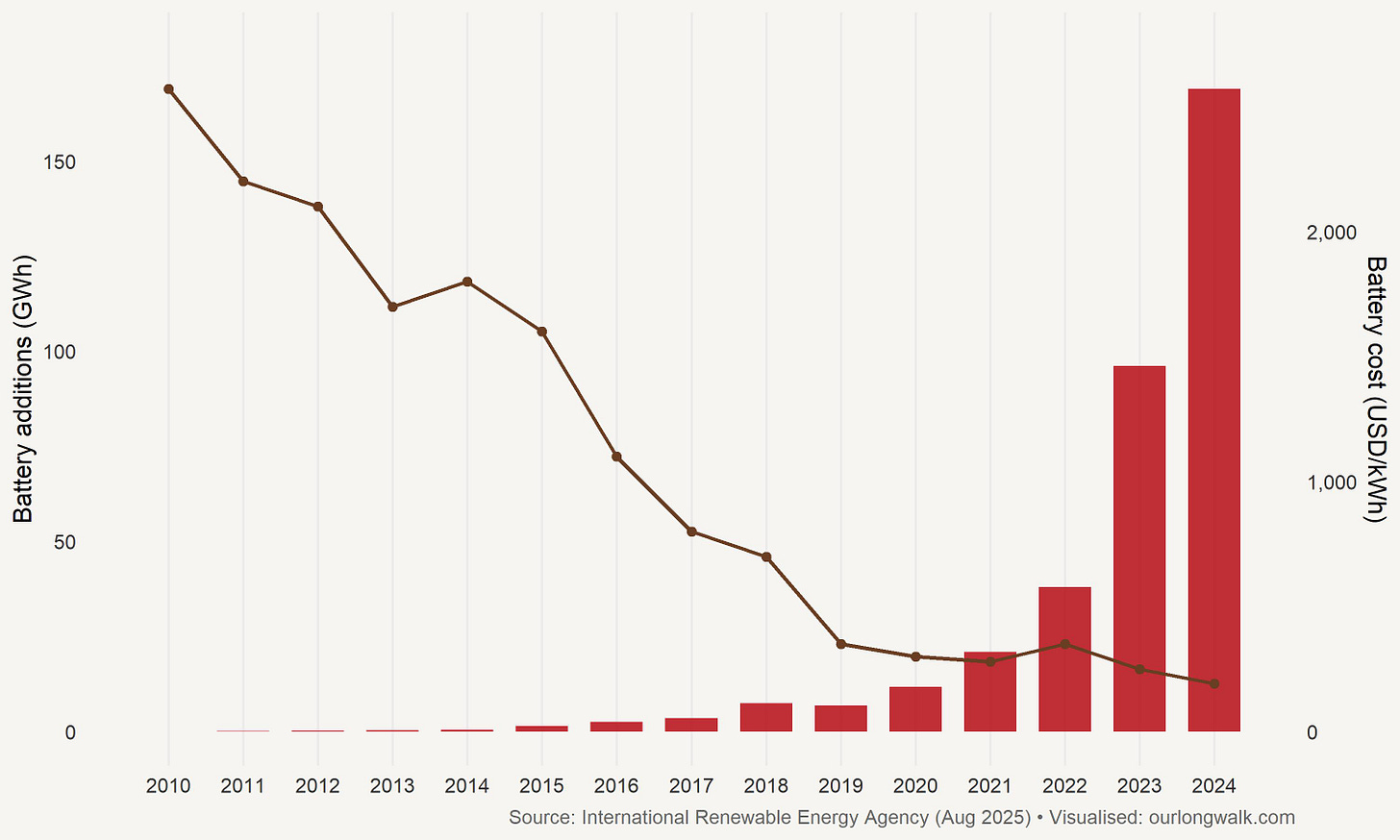

Until recently, batteries were simply too expensive to matter at scale. That is changing. Costs have fallen rapidly, and if current trends continue, battery storage will become economically viable for far more households, firms, and communities – possibly as soon as 2026.

This is where the bee analogy becomes useful. Cheap batteries do not just provide cheaper or cleaner energy. They allow energy systems to behave more like a bee colony: modular and distributed. Instead of relying on one fragile grid, power can be stored locally, shifted when needed, and reconfigured when conditions change. That matters enormously in places where reliability cannot be assumed.

It also enables a redesign of industries. Drones, mentioned above, are one example. But consider transport. In a series of careful engineering–economics papers, MJ Booysen and his collaborators at Stellenbosch show how cheap batteries can fundamentally lower the cost of moving people and goods in environments where distance, poor roads, and unreliable grids have long been binding constraints. In rural Africa, once energy storage becomes cheap enough, electric light vehicles are not a luxury. They are likely to become the default.

The same logic applies in cities. Using detailed data on how vehicles actually move through Cape Town and other South African metros, Booysen and his co-authors show that cheap batteries do not simply lower costs at the margin. They change how firms organise production. Vehicles no longer need to be over-purchased as insurance against fuel price volatility or load-shedding. Charging can be shifted to off-peak hours or paired with on-site solar. Like bees adjusting their foraging when flowers move, firms, if allowed, can now rapidly adapt to conditions rather than relying on permanence.

Here’s my prediction: in 2026, battery technology will – subtly, incrementally, but definitively – change how we produce and consume things. In a country where unreliable energy has taxed almost every sector for more than a decade, this helps explain why batteries may matter even more here than in the places Noah had in mind.

Acacia tree

The world is often described as entering a multipolar phase. That is true, but it misses something important. The world is not only more fragmented; it is also more hostile. Wars in Ukraine and Gaza continue with no clear end in sight. Tensions between China and Taiwan flare regularly. And just last week, the United States intervened directly to depose the Venezuelan leader. Even the rituals that once softened geopolitics are fraying. Last year, Donald Trump openly sought to embarrass South Africa’s delegation and then declined to attend the G20 hosted on African soil. Power is being exercised more bluntly, and more publicly, than before.

One way to think about this moment is through the image of the acacia tree. The acacia survives where little else can. It grows slowly, conserves resources, and protects itself with thorns. That metaphor fits a global system that increasingly rewards resilience rather than cooperation.

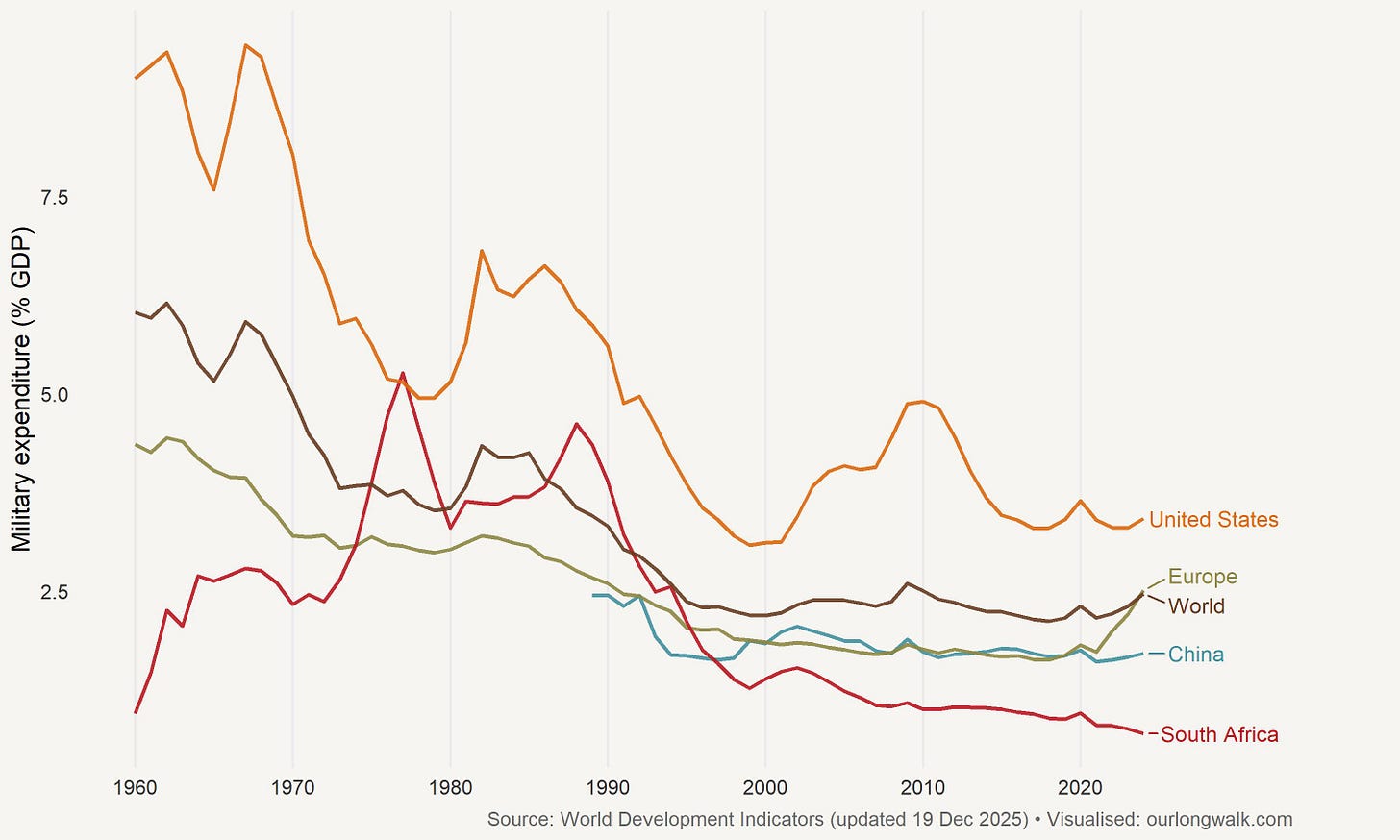

As the figure above shows, defence spending, especially in Europe, is rising – though arguably from a low base historically – and investors are paying attention. Venture capital, long focused on consumer tech and enterprise software, is flowing into military and dual-use technologies. Lists of defence startups to watch now include firms working on autonomous systems, logistics, cybersecurity, sensors, materials, and battlefield communications. As military budgets expand, more entrepreneurs will enter the sector, not out of ideology, but because that is where demand, funding, and long-term contracts are likely to be.

That matters for South Africa. The country has a long defence-industrial tradition, but it has been badly damaged. South Africa does not need to recreate Denel as it was. But it does need an environment in which engineers, entrepreneurs, and investors can build competitive defence and security businesses without political interference. Defence, like energy, is not immune to the basic rules of economics. Innovation follows incentives.

Periods of geopolitical anxiety also tend to produce a cultural response. When the future feels dangerous, societies often turn backwards. The sociologist Zygmunt Bauman called this retrotopia: the search for comfort in an imagined past. We can already see signs of it in politics, art, and popular culture – revived symbols, nostalgic films, promises to “restore” former greatness. In postcolonial societies, this temptation can be especially strong. The past offers certainty, even when it offers little guidance. Like an acacia in a dry landscape, the past will be used as shelter in 2026: familiar, resilient, and defensive – but ill-suited to a world that still needs to grow.

Endurance, however, is not the same as stagnation. The acacia also describes low-growth equilibria: systems that survive, but do not flourish. For much of the last decade, South Africa fitted that description. Growth was weak, expectations low, confidence fragile. Yet 2025 surprised. Growth exceeded pessimistic forecasts. Minerals performed well. And despite the strains of coalition politics, institutions held. As I have argued before, South Africa’s problem has not been collapse, but stagnation.

That is why 2026 matters. If global conditions remain supportive – especially commodity demand – and the Government of National Unity can survive local government elections (and the above-mentioned international turmoil), then South Africa may begin to edge out of its low-growth equilibrium. Not dramatically. Not through a single reform or leader. But incrementally. The acacia does not become a rainforest tree. It deepens its roots. In a hostile world, that kind of resilience may matter more than speed.

Donkey

If you believe in the Chinese zodiac, 2026 is the Year of the Fire Horse – an omen, the South China Morning Post reminds us, of “chaos” alongside “great progress”. One reason people remember the previous Fire Horse year is Japan’s sharp dip in births in 1966, linked to a superstition that made some parents postpone pregnancies.

I’m happy to concede the “volatility” part. But I want to propose a different animal. 2026 will be the year of the donkey.

The donkey is perhaps not the most celebrated of animals, but it is a remarkably resilient one. In Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom, I note that, despite Africa’s abundance of large mammals, “the only exception is the donkey, domesticated from the African wild ass”, and that these wild asses were adapted to harsh environments, needing less water and digesting coarse grasses. The donkey thrived because it turned scarcity into capability by taking over burdens that human bodies could not carry for long.

That is a good way to think about AI agents.

The popular story about “donkey work” is that it means repetitive drudgery. That part is true. As tools like Cursor, Lovable and, most impressively, Claude Code roll out, expect even university professors of economic history to become programmers. (My first app will be available soon. Watch this space.) I don’t plan to make money but to use these tools to become more efficient. Soon there will be agents to help you do your taxes, renew your drivers licence, submit your invoices, basically any task that requires time but no creativity. The point is to free up time for far more productive – and fun – things.

But the donkey metaphor only becomes interesting once we move beyond drudgery. Donkeys are not stupid. The “stubborn donkey” stereotype often hides a more accurate description: cautious, context-sensitive, hard to bully into unsafe choices. Scientific work on donkey cognition is still young, but it is already pushing back against centuries of lazy assumptions. One study, for example, uses a non-verbal, operant-conditioning problem-solving test on 300 donkeys and argues that measurable cognitive variation is real, and that the species has been “traditionally misunderstood” from a cognitive perspective.

Just as important, donkeys are social. They form long-lasting bonds and recognise companions. One study finds that donkeys in a Y-maze preferred their companion over familiar or unfamiliar donkeys, supporting the idea of stable pair-bonds and individual recognition. Another recent paper emphasises this “social plasticity”, noting that domestic donkeys form strong pair-bonds even with unrelated individuals. That is part of why many handlers experience donkeys as empathetic.

Now consider what AI is becoming. Economist Joshua Gans offers one example – “vibe researching” – using ChatGPT to draft, extend, and pressure-test academic ideas, even to the point of sketching papers aimed at top journals, like Econometrica. This is not replacing clerical work. It is substituting scarce human attention with constant machine attention. The donkey is no longer hauling sacks. It is pulling the plough.

But the most important part of the metaphor is what does not change. Even a smart, social work animal needs direction. You can delegate the labour, but not the responsibility for where it goes or what it produces. The donkey still needs a route. The agent still needs prompts, constraints, judgement, and sign-off. And responsibility does not shift just because a draft is machine-generated.

NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang put this bluntly in a Stanford conversation. Talking about his employees, he said:

“You want greatness out of them and greatness is not intelligence … greatness comes from character, and character isn’t formed out of smart people, it’s formed out of people who suffered.”

In a world where intelligence is becoming cheaper – where drafts, code, and arguments can be generated on demand – what differentiates people is less raw cognition and more character: agency, ownership, and accountability. It won’t be ChatGPT that publishes that Econometrica paper. It will be a human author. Which means a human must take responsibility for what is in it.

This is also why I remain sceptical of simple “jobs disappearing” narratives. The best work in economics is increasingly careful on this. An NBER paper using large-scale conversational data argues that ChatGPT’s economic value shows up mainly through decision support in knowledge-intensive jobs, not wholesale automation. Work on AI agents pushes the same task-based logic further: it audits which occupational tasks workers actually want agents to automate or augment, and how that aligns with current capabilities.

Still, there is a catch. Entry-level jobs are often bundles of donkey tasks: summarising, formatting, checking, drafting, cleaning. If those tasks become cheap, the first rung of the ladder changes. Economist Jack Meyer’s point is not that AI will “take your job” tomorrow. It is that AI can disrupt hiring by weakening traditional signals, raising screening costs, and making entry-level roles harder to access. That will be painful. It may also be generative. When the old apprenticeship narrows, more people will build their own ladder. More micro-entrepreneurs. More students shipping small tools. If I were a first-year in 2026, I would do exactly that. Play with Lovable. Build something small that saves real time. Learn how to lead the donkey.

If 2026 is volatile, the answer will not be to chase the Fire Horse. It will be to harness the donkey – and to cultivate the character to steer it.

Amazing metaphors I never expected to learn as much about donkeys as I did agents!

I wonder if 2026 will also be a reckoning year for media (especially social) as the "donkeys" of our time provide the means to significantly alter its market and drive changes in how people want to consume media.

Johan brilliantly written thank you, baie dankie!