The tallest men, then and now

Afrikaners and anthropometrics

When I get on a train in the Netherlands, I immediately notice that I’m shorter than almost everyone. That is different elsewhere. In Italy, my 1.82m is above average and in Japan, I feel like a giant. Why are the Dutch so tall?

A more appropriate question is perhaps: when did the Dutch become tall? See, most of us think height is genetically programmed. And given that genes change relatively slowly, that must mean that the Dutch have been tall for some time. But that’s not true. Around 20% of an individual’s height is determined by environmental factors. If these factors change quickly – and diets adjust accordingly – then the average height of a population can change quite quickly. This is exactly what happened in the Netherlands.

Dutch men are the tallest people on earth with an average height of 1.84m. They are tall because they consume a lot of protein in cheese and milk. This was not always the case: up until the twentieth century, the Dutch were not a height outlier. Some have suggested that assortative matching may also be at play: that tall people tend to marry other tall people and, importantly, have more children. But even this seems unlikely to explain the rapid overall increase in the height of Dutch men.

When South Africans think of tall Afrikaner men – those with Dutch roots in the seventeenth century – they tend to think that there is a genetic similarity. But that’s false. The seventeenth-century Dutch sailors who arrived at the Cape were not tall; the Dutch only gained this advantage very recently. Something else must explain the height of Afrikaners.

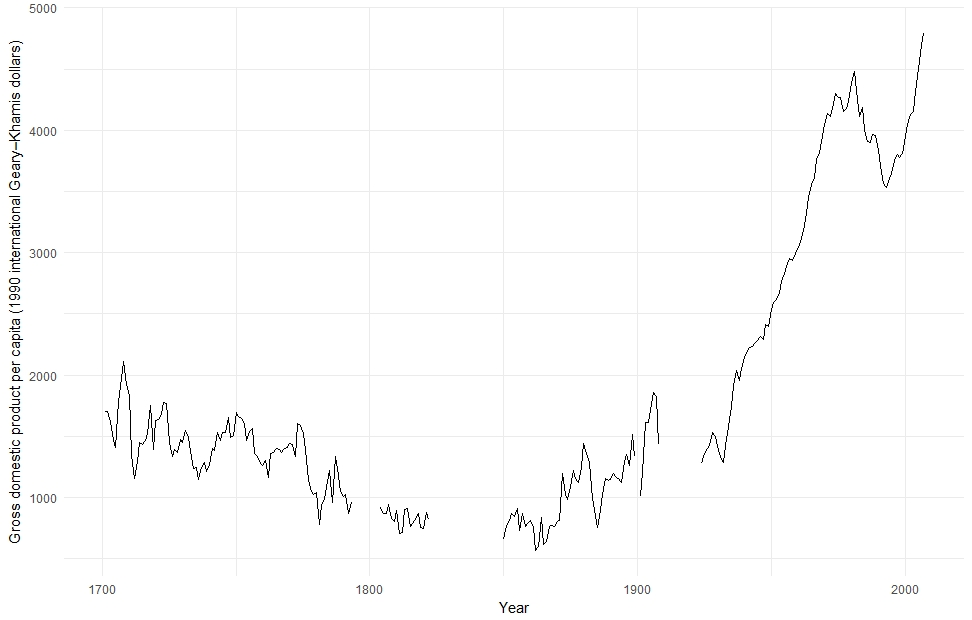

Gross Domestic Product is the conventional measure of a society’s living standards. The more South Africans produce, the more we can consume, and the more we can consume, the wealthier we are thought to be.

But GDP is a recent phenomenon. Although attempts were made to measure a society’s general level of wealth in the eighteenth century already, the method we use today was only developed in the 1930s by the American economist Simon Kuznets. It was accepted as a general measure of economic performance at the 1944 Bretton Woods conference.

One of the tasks of economic historians, then, is to estimate the pre-1940s GDPs of countries. This is easier said than done. The figures that we need to calculate historical GDPs are often simply not available. We have to rely on many assumptions to come to reasonable guesstimates.

It was Angus Maddison who first created such a long-run GDP series for a number of countries. After his passing, the Maddison-project, hosted by the University of Groningen and under the supervision of Jutta Bolt and Jan Luiten van Zanden, has continued to update and expand the series. 169 countries are currently included.

With Jan Luiten, I produced a similar series for South Africa in 2013. Again, we had to make several (strong) assumptions, but ultimately we could produce GDP for South Africa over more than 300 years. The graph below shows an updated figure from 2020.

But GDP is not a perfect measure. Historical GDP estimates can be easily criticised (both for what they include and exclude). It is therefore important to compare these series with other measures that proxy living standards.

This is where height (or stature) comes in. Where GDP requires a lot of information – price levels, consumption baskets, social tables, average incomes, population estimates – height requires, well, only an archival source that records a sample of (men’s) heights. An entire subdiscipline has developed to document these patterns across time and space: anthropometrics.

A few years ago, I met the Canadian economic historian Kris Inwood at a conference. He mentioned that he had transcribed several thousand First World War-soldier heights recorded in attestation forms. These included observations of soldiers who enlisted in South Africa, Australia, England, and Canada. We partnered with Martine Mariotti and ultimately chose to work on a paper that compared white South African men to other settler societies. The paper was published last month in Economics and Human Biology (working paper version here).

We ultimately use five military forces to document the heights of white South African men. To our surprise, white South Africans were the tallest men in the world in the late nineteenth century: an average of around 1.75m. We can say this because we compare them to men in some of the richest societies at the time: Australian, Canadian, New Zealand and English men. When we limit the sample to only farmers, we basically capture mostly Afrikaners. The height advantage is pretty obvious in the figure.

What happened in the twentieth century? Although white South African heights do not decline (apart from a short sharp dip around the Anglo-Boer War), the trend remains flat. That is different in other countries, where men experience large increases, overtaking the South Africans. One reason for stagnation in South African heights is urbanisation: cities not only have fewer proteins but also more diseases. Another reason is simply that South Africans did not experience the same economic growth in the second half of the twentieth century as other countries.

Our results confirm again what many South African historians find hard to believe: that Afrikaners (or Boers) were not impoverished, living just above subsistence. South Africa’s GDP per capita may not have been the highest in the world, but the height of these Afrikaner men suggests that they had reached levels of living standards that most other societies would only achieve in the twentieth century.

* An edited version of this post appeared (in Afrikaans) in Rapport on 14 August 2022. Image source: E7877 Front Gen. Smuts and Boer Officiers (Elliot Collection, WCARS).