The remarkable Maori experience

Human height provide economic historians with a wonderful tool to measure living standards in the past. A society's average height, it turns out, is to a large extent determined by the environment it inhabits during the early stages of life; the more proteins (e.g. milk and meat) we eat at a young age , the taller we tend to grow. This was especially true in the past, when people were poorer and nutrition varied more in different parts of the world.

The past week I attended a conference on Heights and Human Development, organised by Tim Hatton and Martine Mariotti of the Centre for Economic History at ANU in Canberra, Australia. The invited authors used historical heights to measure the diverse impacts of slavery (Rick Steckel), migration (Zach Ward), colonisation (Joerg Baten), social transfers (Diana Contreras Suarez), Chinese industrialisation (Stephen Morgan) and technological change (my own, with Mariotti and Kris Inwood, which will hopefully soon be available as a working paper).

But I particularly enjoyed a paper by Kris Inwood (with two colleagues) that investigated the heights of New Zealand's Maori over the last two centuries. When the Pakeha (the whites from Europe and their descendants) arrived in New Zealand early in the nineteenth century, they described the native peoples as tall and strong. Yet, as Maori lands were taken up by Pakeha farmers, their stature declined: by the beginning of the twentieth century, Moari people had lost their reputation as a tall and strong people, and Inwood et al's evidence shows that they were significantly shorter than their white countrymen.

This gap in the heights of the two groups persisted for more than fifty years, but, and this is the surprising result, by the 1970s the gap had narrowed and by the 1980s had closed completely. Children born to Maori parents in the 1980s are today as tall as their Pakeha compatriots. The exact reasons for this convergence in heights are unclear: Inwood suggested that it was due to government social transfers during the Golden Age, but clear causal evidence is lacking. Yet, I would argue, this is an incredibly important event to understand, because it has implications elsewhere, most notably in South Africa.

Whites in South Africa today are about 8cm taller than their black compatriots. There is no reason to expect that this has always been the case; the gap was almost certainly smaller at the beginning of the twentieth century and, although we have limited data, probably much smaller (and possibly even negligible) at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Two centuries of land dispossession and prejudiced policies saw a divergence in the living standards of South Africa's different race groups. When exactly this happened, and by how much, is the question of ongoing work by myself, students and collaborators. (I will hopefully have more to report later this year.)

Yet Maori convergence suggests that the current discrepancy in height between black and white South Africans is not fatalistic, that aggregate differences in height are not set in stone as most people would tend to think. And more, Inwood et al's evidence show that this could happen relatively quickly: Maori heights increased by 8cm over a 25 year period (from 170cm to 178cm between 1955 to 1980). If black South Africans experienced the same after the end of apartheid, we would have seen the large divergence in height disappearing within this decade.

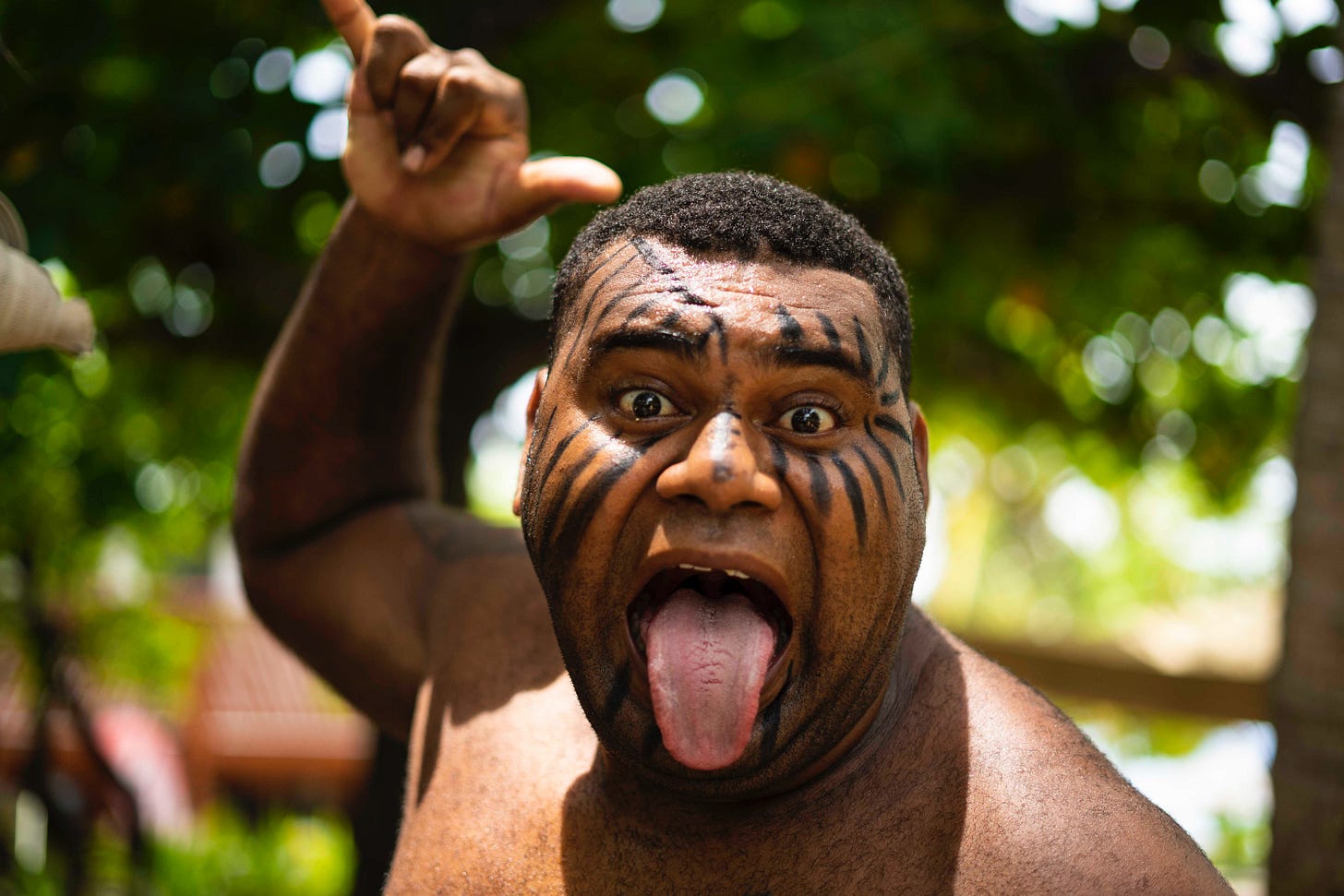

By all accounts, though, despite many improvements in the living standards of black South Africans, the height discrepancies remain. We therefore need to learn whether it was better nutrition, female education, a stronger economy, luck, or maybe even a strengthening of Maori identity and pride (as was suggested at the workshop) that led to the remarkable Maori experience of the mid-twentieth century. This is the challenge for us as economic historians. As the Maori would say: Ma tini ma mano ka rapa te whai. By many, the work will be accomplished.