The problem of information pollution

And what to do about it

This is a free post from Our Long Walk, my blog about South Africa’s economic past, present, and future. If you enjoy it and want to support more of my writing, please consider a paid subscription to the twice-weekly posts, which include my columns, guest essays, interviews, and summaries of the latest relevant research.

I open ChatGPT and enter the following prompt: Write me a song about the Springboks winning the World Cup in 2023. The title: Hulle Weet Nie Wat Ons Weet Nie.

Oh, and include the words ‘Impi’, ‘Rassie’, ‘kant’ and ‘one-point warriors’.

Two more prompts later, I have my lyrics:

Verse 1:

Impi charge, in the morning glow,

Rassie’s tactics, setting the flow.

One-point warriors, stance so bold,

Green and gold, their story told.

Verse 2:

Shoulder to shoulder, kant to kant,

With every scrum, their legacy chant.

Sweat mingles with the earth and sand,

Springboks’ resolve, across the land.

Chorus:

Hulle weet nie wat ons weet nie,

Heroes of twenty twenty-three.

World Cup champions once more

The Springbok story, forevermore.

It all took less than two minutes. (Yes, I timed myself.)

Then I open Suno.ai. It asks me to enter the lyrics of the song I want, the style, and the title. I paste the ChatGPT lyrics, then randomly enter ‘uplifting edm, Afrikaans folk, amapiano, violin drops, old male vocals’ under style. (I don’t know anything about music, but my sense is that these don’t fit together.) I press enter.

Within five minutes, I created a song that can play on any radio station in South Africa. And given that it was virtually costless to do so (both in terms of time and expenses), sales of even just one song would turn me a profit. Tomorrow, I will create 100 such songs. Or why not 1000, or 100,000?

Welcome to the Age of Information Pollution. Exacerbated by the proliferation of AI-generated content, the internet, which once promised unlimited access to knowledge and cultural enrichment, is now at risk of becoming a wasteland of low-quality, untrustworthy information, challenging our ability to discern truth and eroding the foundation of reliable communication. (I asked ChatGPT somewhat ironically to complete the sentence after ‘risk’. I thought it did a pretty good job.)

Take books. Sure, excellent fiction and non-fiction works are still produced every year, but AI-written books now far outpace books written by people. To give a sense of just how bad it is, since September, Amazon has limited authors to only uploading three books per day. For almost any non-fiction bestseller, it is now possible to find a rip-off version: the neuroscientist and author Erik Hoel recently discovered that there are at least three ‘workbooks’ of his The World Behind the World available on Amazon. He writes:

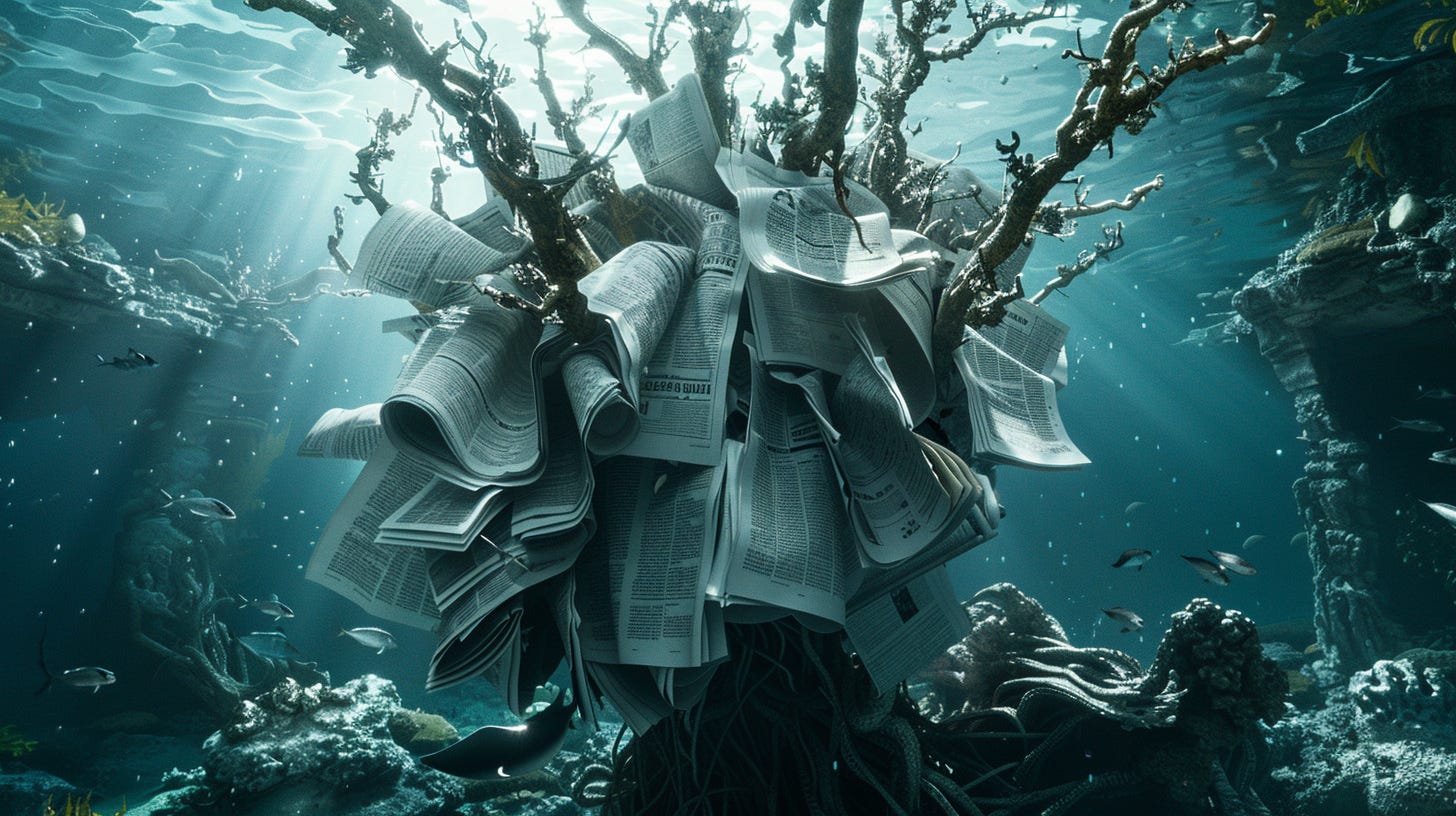

What, exactly, are these ‘workbooks’ for my book? AI pollution. Synthetic trash heaps floating in the online ocean. The authors aren’t real people, some asshole just fed the manuscript into an AI and didn’t check when it spit out nonsensical summaries.

Those workbooks are for sale at $9.99. If only one is sold, then the ‘author’ is already in profit. And given how easy it could be to mistake a fake book for a real one, I’m guessing these digital doppelgängers are becoming increasingly profitable, which explains why they’re proliferating.

Music and books are just two industries affected by the rise of generative AI, but there are many others. From news articles and academic papers (about which I’ve written before) to games and video, much of the entertainment we consume on a daily basis will soon be overrun by low-quality, synthetic content. Those YouTube videos that kids watch for hours on end? They are likely AI-created with storylines that don’t make sense, music with no obvious harmony, and words that don’t even mean anything.

Many are concerned. In his post, Hoel argues that the unrestricted creation and dissemination of content lead to a polluted digital environment, where the quality, authenticity and trustworthiness of information are poor. This is akin to a tragedy of the commons, he says, which, like overgrazing in a shared pasture, depletes the value of the internet as a resource. In short: all this fake stuff, at best, degrades the user experience and, at worst, may actually be harmful.

Perhaps this is an overly pessimistic conclusion. Generative AI, as I’ve noted before, has the ability to enhance creativity, democratise content creation, and even offer personalised experiences. (I can now have my own music channel broadcasting my own music, without ever learning to play an instrument!) It is attractive to think of it as a transformational technology, boosting productivity and lifting living standards.

But a historical example of a similarly transformational technology might help us consider the detrimental effects. The invention of Bakelite in 1907 marked the start of the modern plastics industry. As it could be moulded into various shapes and maintain its form, its popularity soared. Further improvements making it more versatile, durable, and cheaper meant that it played a crucial role during World War 2, used in everything from parachutes to aircraft parts. Post-war, the consumer boom and the rise of disposable culture further fueled the widespread adoption of plastics, leading to our global reliance on it today.

But its popularity had another consequence: marine pollution. By the 1960s already, US scientists discovered that more than 100 million tonnes of plastic waste had been dumped in the oceans. A 2021 Science paper emphasises the poorly reversible nature of plastic pollution. The sad reality is that ‘emissions of plastic are increasing and will continue to do so even in some of the most optimistic future scenarios of plastic waste reduction’.

Plastics’ remarkable versatility and affordability have created a classic collective action problem. As the authors of the Science paper emphasise, attempts to reign in its use have been largely futile. So, what can we learn from the history of plastics that might help us avoid another tragedy?

The typical solutions to the tragedy of the commons involve assigning property rights (privatisation), establishing quotas, creating public policies that regulate access and usage, or developing community management practices where users collectively agree on and enforce sustainable use practices. Of these, I really only see property rights working.

Let’s take news media. I propose that subscription models like News24 or Substack are the way forward. News24 is now the biggest subscription-based news publication on the African continent, with more than 100,000 subscribers in just three years. It has overtaken the circulation of all daily and weekly newspapers in South Africa. Substack allows anyone to publish content, but to avoid the proliferation of low-quality, untrustworthy information, authors are motivated to produce valuable, engaging content as their income directly depends on reader subscriptions and satisfaction. (And, in turn, Substack is incentivised to promote the content of those that attract many paid subscribers.) I can see these incentives play out on my own site: when I publish a piece that generates much interest, paid subscribers sign up. When I produce a substandard essay, free subscribers simply unsubscribe. This pay-for-content system effectively privatises parts of the information commons by making valuable information the key to attracting and retaining subscribers, fostering a space where quality trumps quantity.

The consequence is likely to be a bifurcated internet, with high-quality content in privatised communities and a public domain cluttered with free AI-generated but lower-quality content. Yet perhaps that is the best of both worlds: a system that allows for the flourishing of grassroots creativity while also offering a refuge from the inevitable deluge of less polished attempts – like my AI-generated homage to the World Cup-winning Springboks.

An edited version of this article was published on News24. Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. The image was created with Midjourney v6.

I truly appreciate the comparison of the world wide web to the plastics industry. Entertainment for the masses is as ubiquitous as cling wrap on food punnets, and probably as important! Yes, there are a few discerning folks out there that prefer quality info and like their water in glass bottles but 99.99% of consumers don't even think of the content/quality/validity of the information streamed through their devices in exactly the same way they aren't concerned about plastic recycling! Otherwise we would probably have stopped dumping plastics into the sea.

This low level, invasive, algorithm driven AI entertainment, is as sure to stay with us as microplastics are part of our earthly system, with little choice to avoid it.

What would we do without cling wrap? :)

I think you've proven that Afrikaans contemporary artists have been using AI for many decades! :-D

Seriously though, even before the advent of current AI technologies, music in particular has been foreced to become more of a consumer article with streaming services. AI is accelerating this. I'm not saying there isn't a place for "elevator music", but it seems like certain enjoyers of music are being ignored. For me, as a trained and educated musician (former) this is hard to swallow.