The poorest continent

Poverty will soon be an exclusively African phenomenon and, frustratingly, remain so for long

That we should abolish poverty is not a new idea. But it is also not a terribly old one.

For most of human history, poverty was accepted as the natural state of humankind. We are born with nothing; everything beyond subsistence must be grown, made, or exchanged. To be poor was to live as nature intended, reliant on labour and the seasons. Wealth, by contrast, was exceptional, the product of expropriation. Poverty was not a moral failure but the baseline of human life.

That view began to shift in the late eighteenth century. As Martin Ravallion notes, the radical insight of the Enlightenment was not that poverty existed but that it might be ended. Rousseau and Condorcet argued that inequality was not natural or divinely ordained but created by human institutions. Rousseau traced its origins to property and law; Condorcet believed that better knowledge and governance could reduce it. Jeremy Bentham and Thomas Paine took these ideas further. Bentham proposed progressive taxes that shielded the poor and placed greater responsibility on the rich. Paine outlined a land tax to fund universal stipends and pensions, an early version of basic income.

But it was economic growth rather than redistribution that mattered most. The nineteenth century saw progress against poverty in Europe and North America, driven by industrialisation, rising wages and, yes, the slow expansion of social protection. But it also saw new divisions about who deserved help. Britain’s Poor Laws created distinctions between the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor, with workhouses designed to deter the idle. It was only toward the century’s end, with figures like Alfred Marshall, that poverty came to be seen as an ‘evil’ that economics itself might help to eliminate. In the twentieth century, that insight became global: Roosevelt’s (not-too-successful) New Deal, Beveridge’s welfare state, the post-war consensus, and the 1960s ‘War on Poverty’ each turned the abolition of poverty into a matter of government action. By the time the UN’s Millennium Development Goals were announced in 2000, the ambition was universal: halve the global poverty rate by 2015 – and later, under the Sustainable Development Goals, end it entirely by 2030.

So how are we doing in the fight against poverty today?

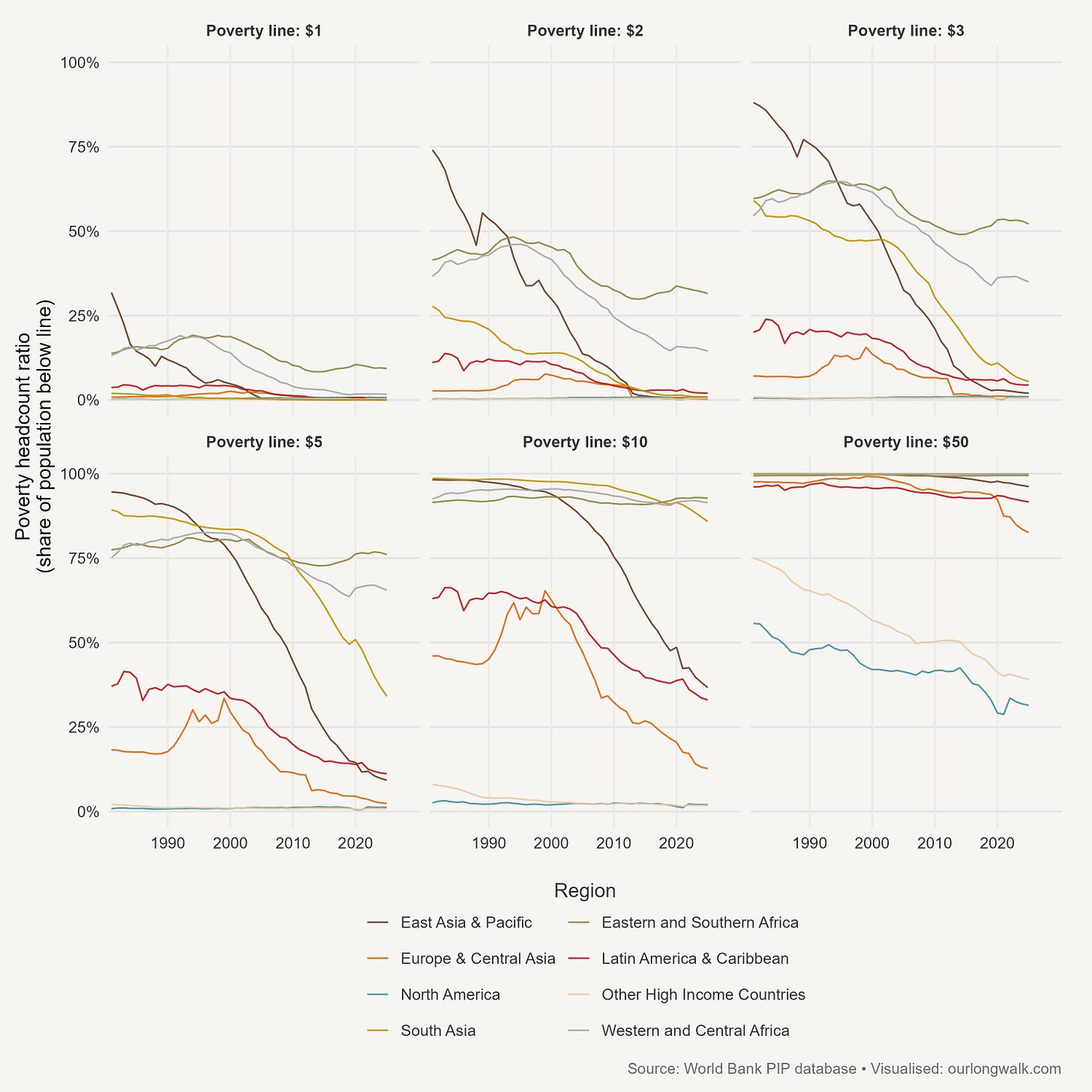

The World Bank has just released a new tool to analyse changes to global poverty since 1990. As the image above shows, across almost every conceivable poverty line – one, two, five, or even ten dollars a day – global poverty has fallen sharply. East Asia’s curve, led by China, plunges from near 80 per cent to almost zero within a generation. South Asia follows more slowly. Latin America’s progress has been uneven but real. Even at higher thresholds like ten dollars a day, the long-term picture is one of rising prosperity. The world, in Ravallion’s phrase, has been engaged in a ‘Second Poverty Enlightenment’: the first time in human history that the majority of people no longer live in extreme deprivation.

And yet, one region breaks the pattern.