The most difficult question of all

What we wear and what it signals

This is a free post from Our Long Walk, my blog about South Africa's economic past, present, and future. If you enjoy it and want to support more of my writing, please consider a paid subscription to the twice-weekly posts, which include my columns, guest essays, interviews, and summaries of the latest relevant research.

For some questions, there isn’t a right answer. What is the definition of success? How do you measure happiness? What is the meaning of life?

But the most challenging one is, of course, when your wife turns to you in the morning and asks, ‘Does this outfit work?’

Sometimes, it’s a choice between being right and being happy.

There’s a deeper truth behind this simple question. We choose our daily outfits within a specific context. Style choices suggest something about our social status, our prestige. This is an old idea in the social sciences. In The Theory of the Leisure Class, Thorsten Veblen writes that the wealthy dress in a way that makes it hard for them to work. The point is to show how unproductive they are:

The dress of women goes even farther than that of men in the way of demonstrating the wearer’s abstinence from productive employment. It needs no argument to enforce the generalization that the more elegant styles of feminine bonnets go even farther towards making work impossible than does the man’s high hat. The woman’s shoe adds the so-called French heel to the evidence of enforced leisure afforded by its polish; because this high heel obviously makes any, even the simplest and most necessary manual work extremely difficult. The like is true even in a higher degree of the skirt and the rest of the drapery which characterizes woman’s dress. The substantial reason for our tenacious attachment to the skirt is just this; it is expensive and it hampers the wearer at every turn and incapacitates her for all useful exertion. The like is true of the feminine custom of wearing the hair excessively long.

For this reason, style has always been a serious matter – and there have been many efforts to regulate it. The sumptuary laws of the eighteenth century imposed hefty fines on those who dressed above their status. Different religious groups have different rules, rules that naturally also adapt over time: Should women cover their hair? Can they wear hats in church?

Hairstyles can particularly irritate people. Sometimes certain hairstyles are used to isolate specific groups: prisoners (and freshmen, back in the day) have their hair shaved off, or think of a monk's tonsure. Even in more liberal societies today, social norms and conventions still regulate what we can and cannot do with our hair. I still remember my principal's reaction when I showed up at school with peroxide-blond hair after a cricket tour. And think of the frequent conflicts in schools where black students feel that old conventions around hairstyles don't apply to them.

But here’s my hypothesis: our (hair)styles are becoming less unique. Society has cramped our style.

It started as an observation. I’ve worked on a university campus for 25 years now. I remember seeing a wide variety of outfits in the early 2000s, from barefoot students to Y2K styles, from goths to grunge, emo to punks, and jocks in rugby jerseys. Walk on campus today, and everyone looks like tech nerds.

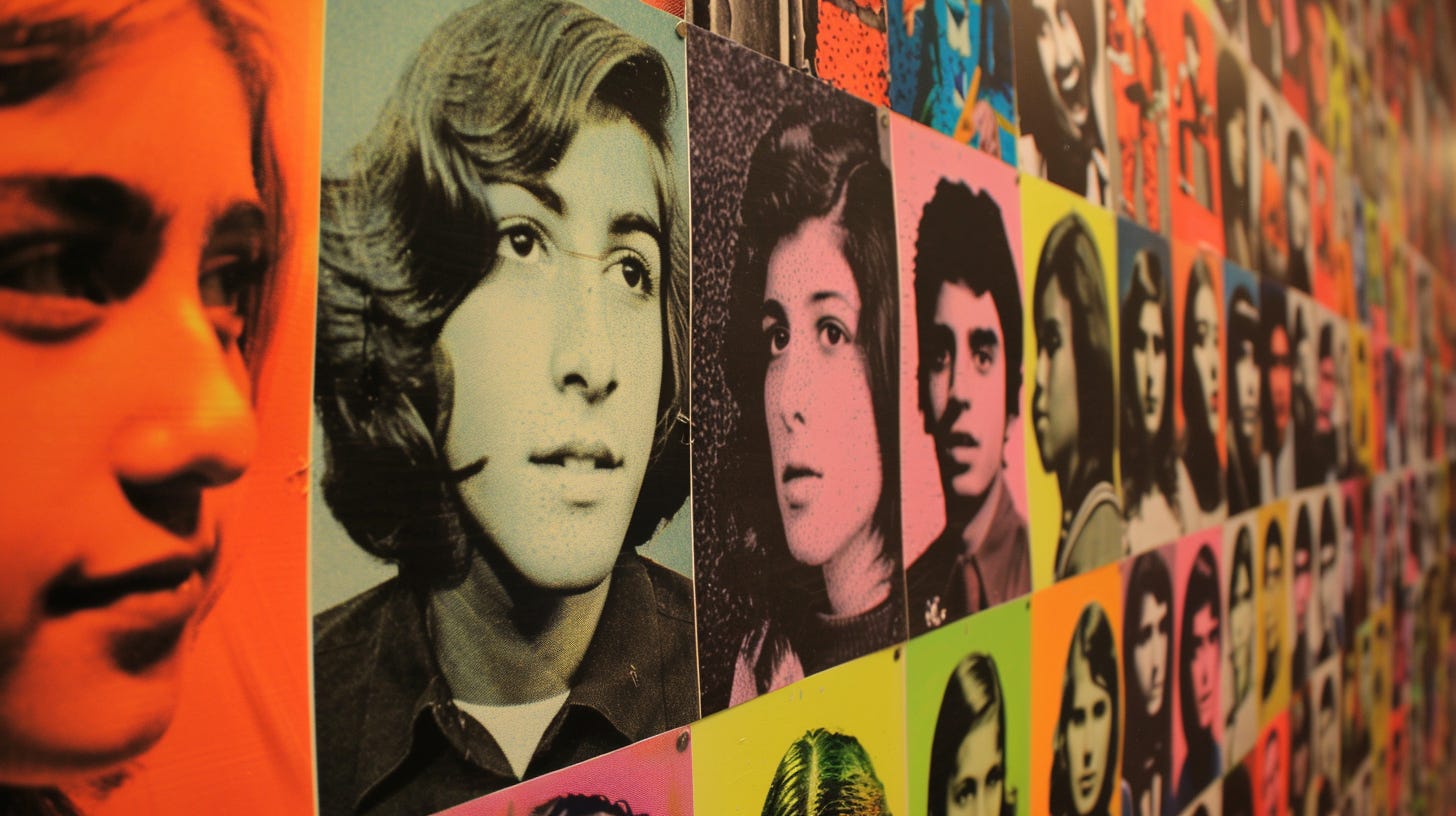

But one observation is not enough to prove a hypothesis. So how does 14 million sound? That’s the number of photos two economists, Hans-Joachim Voth and David Yanagizawa-Drott, used in their latest study to measure the change in style (or appearance) in America. They used 112,000 high school yearbooks from 1930 to 2010 to train a deep neural network to identify style characteristics like hair length, hairstyle, the use of necklaces, the wearing of ties, or the depth of necklines of teenagers. This enabled them to calculate three key metrics: individualism, persistence, and innovation.

What did they find?

Perhaps it’s useful to first explain what these metrics mean. Individualism measures whether people are allowed to make choices that differ from those of their peer group. The absence of individualism is a sign that the cost of deviating is high. It’s also a sign that society will be less innovative because individualism and creativity – a building block of innovation – are closely intertwined. (See, for example, chapter two of Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom.)

Their second metric, persistence, measures how similar style choices are within a given group when that group is compared to students at the same high school a generation earlier. Voth and Yanagizawa-Drott compare groups of students twenty years apart. A culture with high persistence means similar styles over time – senior students of the given year will, on average, look the same as those who graduated twenty years earlier. Low persistence, of course, means culture changes quickly.

The third metric is innovation. It measures style combinations that did not exist before. Students can not only deviate from previous generations in the same school (persistence) or from their peer group (individualism), but they can also have an entirely new style that has not been seen before. Innovation is a stronger version of individualism, a sign that someone dares to be different.

The results are fascinating, precisely because they differ so much for men and women.

Up until the 1960s, the culture reflected in American high school photos was remarkably stable. Men almost exclusively had short hair and wore dark suits with ties. Shirts had collars. There was no sign of moustaches or beards. In short: Individualism for men was low, and persistence was high. Women were the opposite: high individualism and low persistence. Although innovation was slightly higher among women, it was relatively low for both groups and stable until 1965.

Then came counterculture. Or, more precisely, Woodstock. Voth and Yanagizawa-Drott explain:

Consistent with the notion of counterculture, men increasingly deviated from the looks of the parental generation, as well as recent cohorts before them. Importantly, there was not a uniform shift in styles locally, which would just signal a new manifestation of conformist behavior. Instead, similarity among peers declined precipitously. At the same time, levels of individualism and persistence between men and women began to converge – by the 1990s, men and women showed near-identical levels.

Along with this, the pace of innovation accelerated; new styles emerged that had never been seen before in high school photos. By the mid-1970s, the likelihood that someone would have an entirely new style was three times greater than just a decade earlier. And while individualism slightly waned and persistence has increased since then, style innovation has continued to rise; by 2010, the last year of the analysis, style innovation was at its peak.

There are many more interesting results in the study. Regional differences are particularly fascinating. The authors find, for example, that although there were initially few differences between places like New York and Alabama, today there are significant differences in the trends of individualism and persistence. This, they write, ‘is part of a broader pattern of polarization in American society since the 1970s’.

Do these style changes have a socio-economic origin? Indeed. When they look at correlations, Voth and Yanagizawa-Drott find that higher income groups are associated with greater individualism and style innovation. This is, of course, not causal; there are many other invisible factors at play. Indeed, when they control for regional effects, the relationship turns negative. What is interesting, though, is that race doesn’t really play a role over and above socio-economic status.

The most interesting result of the study, however, is the effect of style innovation on actual technological innovation, measured by new patents. The authors find that those in areas that create many new styles also file more patent applications and are granted more patents. While individualism and persistence don’t strongly predict technological innovation, style innovation does. This doesn’t mean that wearing unique clothes causes more patents. Rather, it suggests that high school environments with a liberal culture that allows (or perhaps even encourages) students to stand out are also home to students who, later in life, invent new solutions and products.

Voth and Yanagizawa-Drott’s study ends in 2010. I would love to know what has happened since then, or if my hypothesis that everyone looks the same today is indeed correct. And I wonder how a country like South Africa, cut off from the outside world (but also not entirely), and then opened up, a country with enormous socio-economic differences and diverse cultures, would fare in such a study.

One thing is clear, though: If I were to consider only my socio-economic prestige, the correct answer to my wife’s ‘Does this work?’ would always be: ‘Go wild!’ Happily, she is always right.

This is an edited version of my monthly column, Agterstories, on Litnet. Amid the decline of serious, balanced opinions globally and the reduction of Afrikaans in higher functions in South Africa, LitNet seeks to offer a space for those interested in current events and critical thinking. The images for this post were created using Midjourney v6.

The increasing uniformity of clothing that you observe, Johan, must surely have a lot to do with its increasing cheapness and availability. Take women’s clothing. Up to quite recently most women made their own clothes (only the rich could afford to buy ready made). Home production meant a lot of individuality. Now very few women sew. They buy from big companies producing identical items. Where individuality used to be the cheap option, now the cheap option is conformity. The loss of individualism in women’s clothing also isn’t a simple matter of the cost of deviating being high. In the days of home sewing, there was in fact pressure to deviate – it was a social disaster for a woman to find herself in company with another woman wearing the same dress as her. Today it's no big deal. I think there are many complicating factors for a study that tries to link individuality in clothing to inventiveness and creativity.