Slavenomics

A lot has been written about the negative consequences of the slave trades, both for the origin regions (Nunn 2008) and for their destinations (Engerman and Sokoloff 2011; Fourie 2011). But investigating slavery can add to our understanding of economic theory: Suresh Naidu, for example, use newspaper reports of runaway slaves in the United States to argue that the weak enforcement of property rights in people (i.e. slavery) discouraged investment in slaves and encouraged investment in manufacturing and infrastructure. Instead of the traditional link between strong property rights and economic growth, Naidu's research suggests that the weak enforcement of "bad" property rights can also lead to a favourable long-run outcome. Listen to him here.

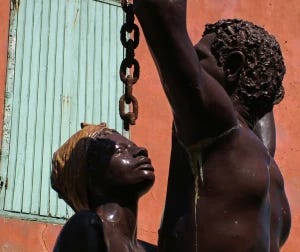

In a recent ERSA Working Paper, Joerg Baten and I have a slightly different aim: we want to know what the levels of comparative eighteenth century development was like for different Indian Ocean regions. Slave records usually reveal very little useful information that allow economic historians to ascertain relative standards of living of the countries slaves originate from. Heights have been used as the most reliable proxy (Steckel 1995), but is often only available for the US South whose slaves originate from the West Coast of Africa. (I visited Dakar in 2007. Both pictures were taken on the island of Goreé, entrepot of the early slave trade off the coast of Dakar, Senegal. The top picture is of a window in a slave house, the one below of the monument marking the abolition of slavery).

The statue on the island of Goree (Dakar, Senegal) to mark the abolition of slavery.

Joerg and I use a novel technique known as age heaping to ascertain differences in the levels of human capital (education) of the slaves brought before the Cape Courts of Justice. Cape inhabitants did not only include slaves from other African regions (Mozambique and Madagascar) and several Indian Ocean countries (modern India, Malaysia, Indonesia, and even China), but also included the native Khoe and San and European settlers. This hodgepodge of individuals allows for a unique comparison between contemporaneous levels of 18th century development across three continents.

We find high levels of numeracy for European settlers at the Cape Colony, similar to their counterparts in the regions of origin in Holland and northwestern Germany. Yet, the most revealing results are for eighteenth century slaves of various origins. Slaves from India, Indonesia and Mozambique had significantly lower levels of numeracy than slaves born in the Cape Colony, while Chinese slaves performed slightly better (although sample size issues may be problematic). Formal education in the slave lodge, imitation behaviour and, perhaps, better nutritional status may explain the relatively better performance of locally born slaves. The lower numeracy scores towards the end of the eighteenth century reflect a change in international trade patterns, with new trade routes and slave middlemen being responsible for the selectivity bias. Perhaps surprisingly the native Khoesan did not perform significantly differently from Cape-born slaves, although a sharp fall in their numeracy-levels is found for the period following their integration into the settler economy.

Such records, techniques and results begin to open a window into a richly textured world previously hidden from our view.