Skyscrapers for the Transkei?

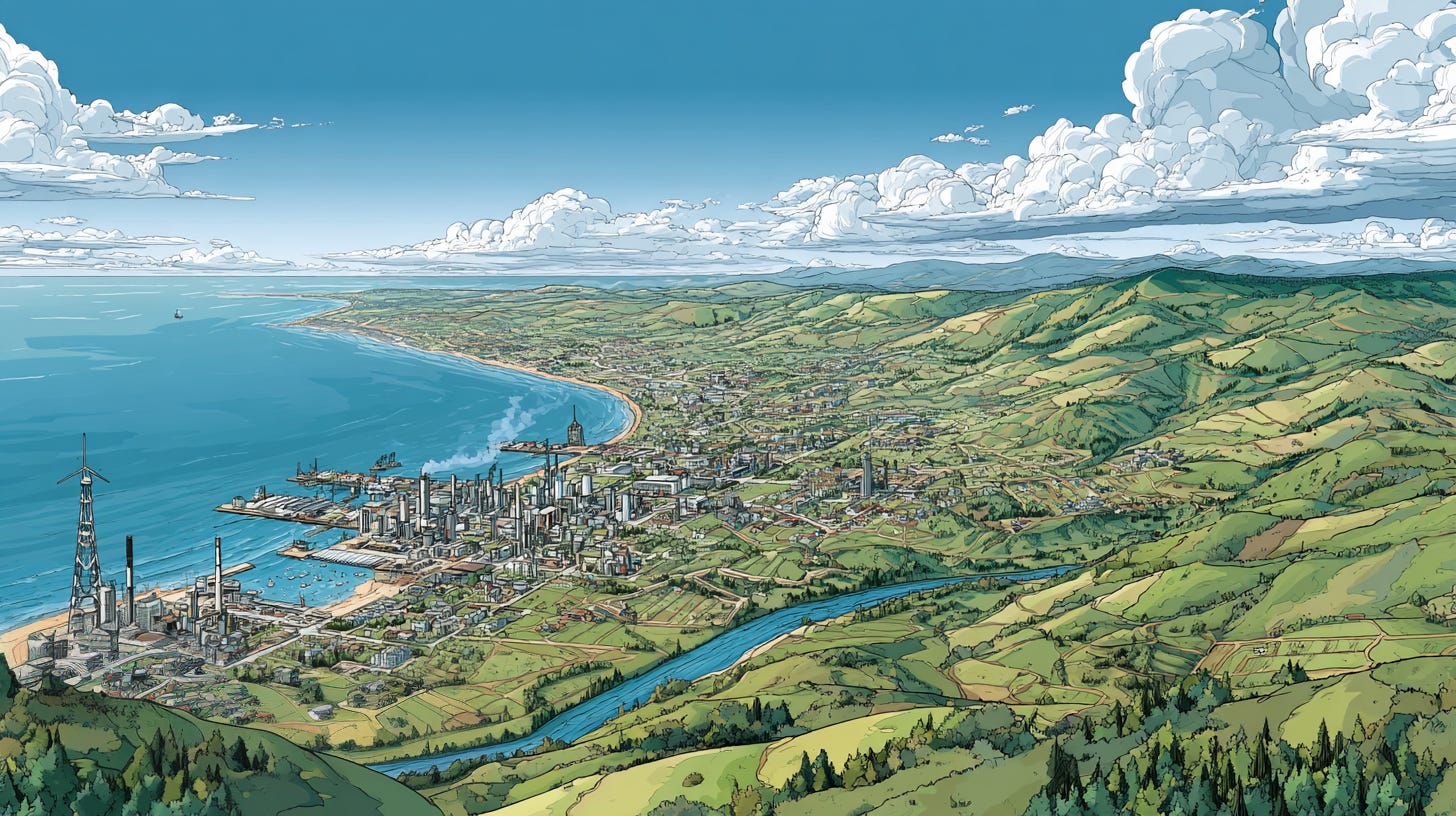

We need more ambitious plans to develop the former Homelands. Charter cities is a viable option.

Drive east along the N2 from East London, turn right onto the R349 and follow it until the tarmac stops at the Great Kei River. Kei Mouth sits on the western bank, roughly an hour from King Phalo Airport. On the eastern bank, reachable only by ferry, begins the former Transkei. The land there is state trust land under the Qolora Traditional Council.

Now imagine the chief of Qolora wants a better future for his community. He could push for upgrades to roads, electricity and water, but money is tight and public programmes move slowly. He could allow people to hold land as private freehold, yet once land is sold the community may never get it back. He could try to run more services directly, but the council does not have the staff or systems to manage contracts, utilities and maintenance at scale. Lobbying provincial politicians, especially in a province as poorly run as the Eastern Cape, rarely produces change that is both fast and deep.

There is another option: The council could partner with a private city builder. The idea is to take a defined area of land – say 20–30 square kilometres – and lease it for 99 years to a developer. In return, the developer pays for and builds the core infrastructure, sets out streets and utilities, and helps set up the basic institutions that make a city work. Ownership of the land remains communal in a trust so the community keeps control. Revenues raised in the city – rent, local taxes and service charges – are reinvested in the area.

To see the range of options, look at Próspera in Honduras. It sits at the far end of the charter‑city spectrum, with a legal regime that gives it wide autonomy on taxes, regulation and commercial law, plus private arbitration and a very liberal code. It has attracted entrepreneurs and controversy, and its legal footing has been challenged in national politics and in the courts. I’m not arguing for an exact replica; the lesson, instead, is that charter cities can be designed with very different levels of risk and autonomy.

A charter city is simply a new urban area inside a country that operates under a specific charter – a clear rulebook – agreed with national and provincial authorities. It is not a fenced‑off industrial park where nobody lives; charter cities are ‘normal’ cities in that they have residential, commercial and industrial activities. Think SimCity, but in real life. The main difference is that they are operated by a profit-seeking private entity that is incentivised to make it easy for business to flourish. Property rights are recorded clearly. Business approvals go through a one‑stop process rather than a maze of offices. Utilities are delivered to published service levels so people know what to expect. Disputes are resolved quickly and predictably. The essential idea is credibility in the rules: when rules are consistent and services actually work, households settle, firms invest and planning becomes possible.

There are good economic reasons for such a model. Secure tenure and predictable approvals reduce risk for investors. Clustering – firms and workers locating near one another – raises productivity because people can share infrastructure, find suppliers and hire more easily. The daily cost of doing business falls when electricity, water, waste services and basic security are reliable. Neighbouring areas benefit too: farmers and transport operators get new demand, local services find new customers, people can choose to commute rather than move, and land values at the city’s edge tend to rise. And because the land stays in a community trust, some of these gains are captured for local priorities such as scholarships, clinics and small‑business support.

There are existing African examples to learn from. Tatu City on the edge of Nairobi is one of the continent’s most advanced private new cities. It combines a special‑zone framework with private management and has drawn manufacturing, services and education. The attraction is the bundle of public goods it now offers privately: clear title, fast permitting, working utilities and consistent enforcement of rules. In Zanzibar, Fumba Town shows how an investment regime, serviced leasehold plots and a clear development code can deliver housing and local services at scale. Nigeria and other countries are exploring similar ventures. None of these projects follows the Próspera blueprint; each has been adapted to local institutions and constraints.

It is worth noting that the Wild Coast has seen big promises before, including a Chinese‑backed lease reported in 2019 that bundled ports, fisheries, housing and a ‘Disney playground’. The plan here differs in one crucial way: it is market‑disciplined. There is no foreign guarantor and no carve‑out from constitutional protections. Risk sits with the operator rather than the taxpayer. Tenure is bankable through long leases or sectional title recorded in a modern cadastre.

If one such city works, we should not stop at one. South Africa could test several charter cities, each designed to answer a different question. One could begin as a digital‑first community and later expand its land area. Another could specialise in a clear sector – agro‑processing, renewable energy or business services – to build deep local skills and suppliers. A third could trial more far‑reaching but still constitutional tools, such as targeted labour‑law flexibility or bespoke tax instruments, to measure their effects on investment and employment. The aim is to be ambitious and empirical: try several models, learn quickly which combinations of governance and economics draw capital, create jobs and earn public support, then adopt the successful pieces more widely.

The key issue is not whether this model is perfect. It is whether leaders are willing to try something new and practical. The President has spoken about smart cities, yet progress has been thin. The former homelands remain the poorest parts of South Africa, and cities are where opportunity and upward mobility tend to concentrate. So should the people of Qolora wait for the next plan from above, or test a focused institutional alternative on a small piece of land with the potential for large spillovers? It is time to turn the Kei from where the road ends into where progress begins.

An edited version of this article was published on News24. Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. The image was created with Midjourney v7.

Waterfall City in Midrand is such a development

I often though entrepreneurs could buy entire villages in the Northern Cape or the Eastern Cape and turn them into sports performance centres, cultural centres - a good solution also to temper mass urbanisation.