Policy uncertainty is killing investment in what matters

Much has already been said about South Africa’s inefficient public sector. Not only has the public sector wage bill escalated beyond the realms of the sustainable, but this has come at almost zero public sector productivity growth. In other words, we are paying more for government to do less. Add to that the poor performances of state-owned enterprises like Eskom, the SABC and most notoriously, South African Airways, and it seems that there is little more that the South African government can do to hurt the prospects for economic growth.

But there is. A new NBER working paper, published by Jose Maria Barrero, Nicholas Bloom and Ian Wright, uses new data on about 4000 US firms to investigate the sources of uncertainty in the US economy. They first distinguish between short-term and long-term uncertainty, identifying the factors that cause each type of uncertainty. They then ask how each type of uncertainty affect firms’ behaviour.

Short-term uncertainty, they find, is caused by oil price volatility. In contrast, economic variables like the oil price has less of an effect on long-term uncertainty where political risk, like policy uncertainty, has a much larger effect. The important result is that short-term and long-term uncertainty have different consequences for firm behaviour. Short-term uncertainty affects employment; long-term uncertainty affects investment in research and development.

If we assume this is true for South Africa too, how would it play out? Volatility of several macroeconomic variables, like the oil price and exchange rate, cause higher short-term uncertainty. This would likely make firms unwilling to hire new workers, or make managers unwilling to offer higher wages. These are the consequences economic commentators typically cite when referring to an unstable macroeconomic environment.

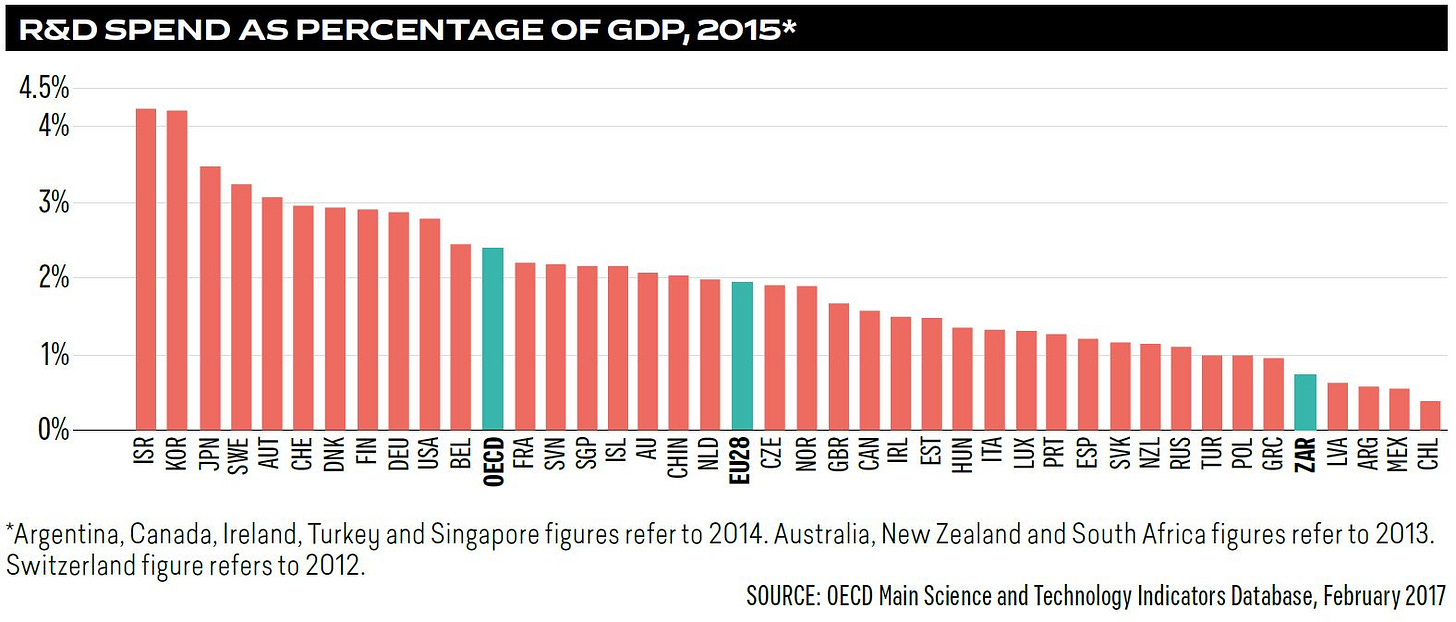

But employment and wages are not the only variables affected by uncertainty. One of the key indicators of a thriving economy is businesses’ willingness to invest in research and development. Take R&D as a percentage of GDP, shown in the Figure below. There is large variation in the share that countries spend on research and development: Israel and South Korea, for example, spend more than 4% of their GDP on R&D. South Africa spend less than 0.8%. (This figure almost reached 0.9% in the 2006-2008 period, a period not surprisingly correlated with high growth rates.)

There is a strong positive correlation between countries that grow fast and those that invest in research and development. South Africa, unfortunately, significantly lags those countries at the technological frontier. It is important, though, to understand why this is the case. It is not only government that invests in R&D; in fact, more than half of all R&D investment in South Africa comes from the private sector.

So what will encourage businesses to invest more in R&D? Well, according to Barrero, Bloom and Wright, political risk and policy uncertainty is the biggest determinant of private sector investment in R&D. In a political environment with little policy coherence, business are unlikely to make investments where the returns can only be realized in the long-run. Even if the possible returns are substantial, a rational investment response to a murky policy environment would be to sit back and see what happens. Lower investment in R&D means falling further behind international competitors.

There are some in the South African government who realise this. Minister of Science and Technology, Naledi Pandor, has committed to doubling R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP by 2020. This is commendable, but in the current budgetary environment, unlikely to get the support from the Minister of Finance. Other initiatives to get the private sector investing in R&D, like a refundable tax credit that will benefit small businesses, have not been implemented.

These problems are not unique to South Africa. As the authors argue: ‘Our findings are significant in the wake of recent events like Britain’s vote to leave the European Union and Donald Trump’s assumption of the US Presidency, which have generated considerable uncertainty over future economic policy around the world. As we have shown, such policy uncertainty is particularly linked with long-run uncertainty and in turn with low rates of investment and R&D that can have significant consequences for the global economic outlook in years to come.’

R&D is the bedrock of future prosperity. Political risk that leads to policy uncertainty hurts not only economic growth and employment creation, but also deters firms from investing in the one thing that can create prosperity for all. If the ruling party is serious about its slogan, it better start by enacting more coherent economic policy.

*An edited version of this first appeared in Finweek magazine of 21 September 2017. Photo by Adi Goldstein on Unsplash.