On foxgloves, flies and making culture fashionable

How the field of cultural evolution can provide new insights into solving social, political and business challenges

This is a free post from Our Long Walk, my blog about South Africa's economic past, present, and future. If you enjoy it and want to support more of my writing, please consider a paid subscription to the twice-weekly posts, which include my columns, guest essays, interviews, and summaries of the latest relevant research.

My wife recently planted three foxgloves in our garden. They bloom beautifully, but when a friend mentioned that the flowers are poisonous, I suddenly lost my appreciation for them. In a house with two little children, they have to go, I told her.

But then I read the latest research on cultural evolution by Joseph Henrich and others. How is it, Henrich asks, that we as a species can be so successful given so many things working against us? We are pretty weak, relatively slow, and poor tree climbers. We cannot distinguish poisonous plants like foxgloves from food with our senses, and our stomachs cannot process toxins. We cannot survive without cooked food, yet we cannot make fire without help. Our babies cannot take care of themselves. And the most surprising is that we are not very smart, that our success as a species does not depend on our intelligence.

How is it that we, rather than elephants or wolves or gorillas, dominate the planet?

Our secret, of course, is that we can learn from each other; we are the only species with ‘culture’. Over the last million or so years, the climate has become increasingly unpredictable. This meant that our genes could not adapt quickly enough, and we had to learn to rely on others.

One of the first places where we began to cooperate, writes Cat Bohannon in her new book Eve, was during childbirth. We are the only species that relies on others to give birth; the midwife was one of the first ‘professions’. Cooperation during childbirth and the early years of infancy meant that we could have children with larger brains, which made further cultural evolution possible; the latest research supports the idea that language, for example, developed alongside stone knives and other primitive tools.

So, unlike other animal species, we do not have to wait for the (slow) natural selection of genes to adapt to our (rapidly changing) environment; we can simply learn from the more successful ones – those with more experience.

Two studies published in 2019 wonderfully summarise this difference between us and animals. (Here I borrow from the Substack blogger Steve Stewart-Williams.) One study investigates the evolutionary reason for zebras’ black-and-white stripes. I always thought the stripes evolved for the visual illusion that could confuse predators during a hunt. But the latest research shows that the patterns instead confuse insects like tsetse flies and horseflies, making it harder for them to land and bite the zebra. This reduces the spread of diseases carried by these insects.

How do the authors know this? They painted a cow with black-and-white stripes and then counted the number of insects around it. Their surprising finding was that striped cows attracted half as many flies. You might think it’s just the paint. They also painted some cows entirely black, but these cows attracted as many insects as the unpainted ones. The long and short of it: striped patterns significantly attracted fewer insects. Next time mosquitoes bother you, maybe wear your WP jersey.

But while animals had to develop genes over thousands of years to give them stripes, humans could simply develop a culture that mimicked the animals’ biological changes. Take the Himba of Namibia. They paint their faces to protect themselves from the ‘African sun and parasites’. A second group of researchers – using painted dolls as test subjects – found that painted patterns on humans also lead to fewer insect bites, just like with zebras. Traditions and beliefs emerged and established practices, such as painting one’s face and body with patterns, which provided an evolutionary advantage to those who practised them.

But cultural evolution is not just limited to the distant past. We are still adapting to a changing environment. Technology requires us to adapt ever faster, and some of our old traditions, superstitions, and customs might now be holding us back.

Take, for example, polygamy, the practice where a man can have more than one wife. In 2011, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that legislation banning polygamy is legal. The argument is based on the testimony of Jo Henrich, who argues that monogamy leads to more peaceful societies. Polygamy results in a surplus of unmarried men. These men then choose high-risk strategies (such as crime) to obtain enough resources to afford a mate. The extent to which entrenched cultural practices such as polygamy, bride price, and cousin marriages affect social outcomes such as social mobility, single-parent families, and crime is a fascinating area of future study, in South Africa and elsewhere, with significant policy implications.

The field of cultural evolution is not only applicable to our social institutions but also relevant to our politics and business world. Take corruption, for instance. Humans have a deep-seated need to favour our family and friends; it has been part of our survival for thousands of years. This nepotism and cronyism still live with us at all levels of society. Yet we know that transactions based on personal relationships rather than impartial institutions typically limit economic growth; if your pool of candidates comes only from your circle of friends, the chances of finding the most suitable person for the job are slim. So how do we counteract this primal need for nepotism? One way is to acknowledge it and incorporate it into anti-corruption strategies, writes LSE economist Michael Muthukrishna. Move people around regularly within organizations, for example. Perhaps a cabinet reshuffle every now and then isn't a bad idea.

In his book The Geek Way, Andrew McAfee uses insights from the cultural evolution literature to explain why certain tech firms thrive. He identifies four norms of a successful organizational culture. Science requires a culture of experimentation. Openness involves accepting failure and promoting transparency. Speed requires constant iteration and adaptation. And ownership fosters autonomy and direct accountability. When these norms are absent, firms tend to fall into bureaucracy, chronic delays, and a culture of silence that discourages innovation. In short: organisations that are not culturally adaptable die out.

Humanity has succeeded because we can learn from each other. There is still much more to understand about how, from whom, when, and why we are better at learning some lessons than others. This is what makes the interdisciplinary field of cultural evolution so exciting: it requires insights from psychologists, economists, historians, biologists, mathematicians, and more.

Many of these theories may be beyond my grasp, but one thing I do know: My little girl may not know that foxgloves are poisonous. But she can learn.

An edited version of this post appeared (in Afrikaans) in Rapport on 14 July 2024. The images were created using Midjourney v6.

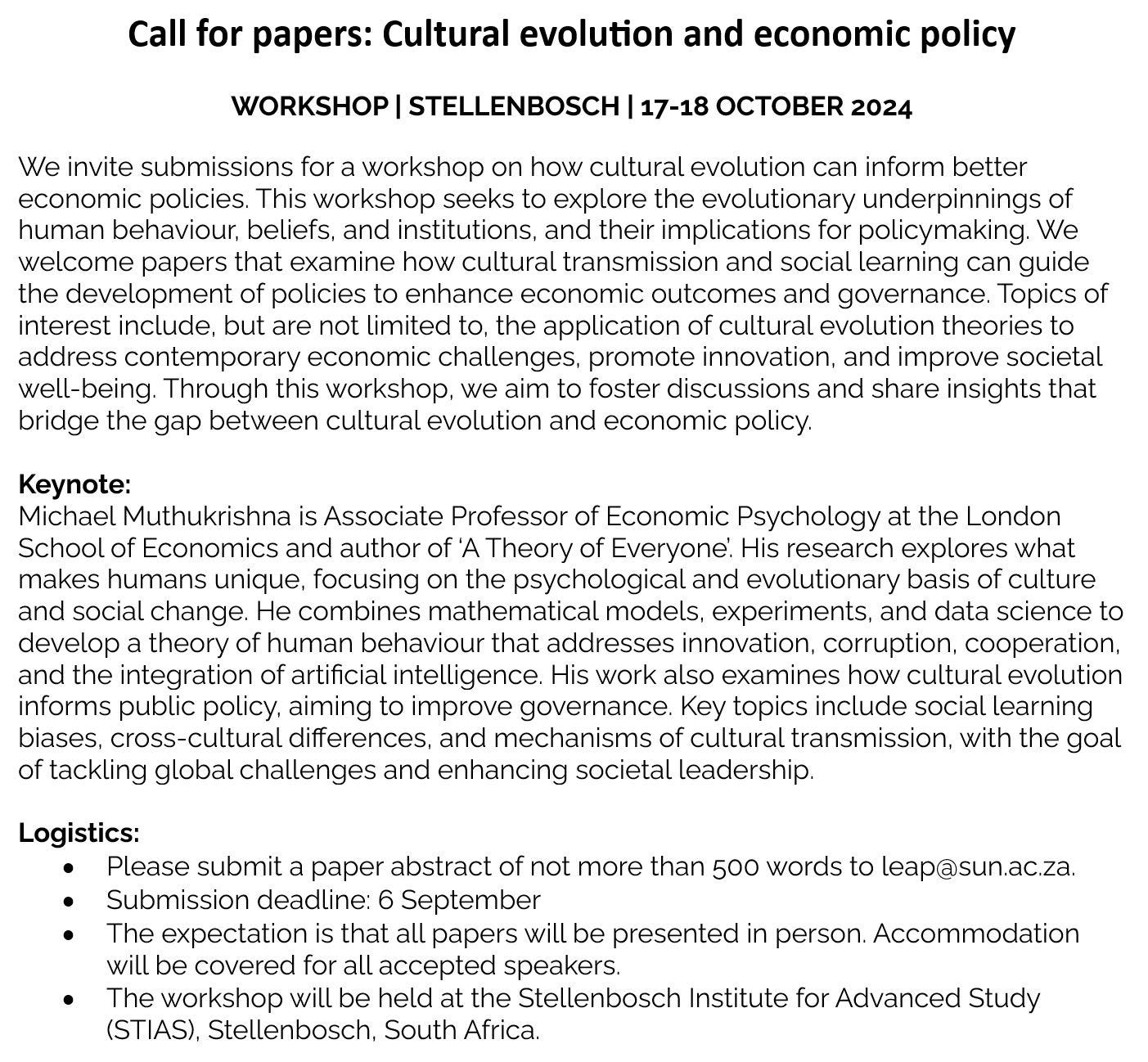

In October, my research unit will host a workshop in Stellenbosch on ‘Cultural evolution and economic policy’. Michael Muthukrisna will be the keynote speaker. If this topic relates to your research interests, please consider submitting a paper. See the Call for Papers below.