The inequality of boredom

Let's not romanticise something our ancestors despised

The Nobel economists Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo tell a fascinating story about a Moroccan villager they met while conducting research. Despite clearly struggling to feed his family, the man owned a large television with a satellite connection. When they asked him why he had spent so much on a TV, his answer was disarming: there was simply nothing else to do. In a village where work was scarce and with few public amenities, the television filled not just his evenings, but the long, empty, boring hours of each day.

The story highlights a fact often overlooked by economists: boredom is unequally distributed. In affluent societies, boredom has become rare enough to be missed, even romanticised. In poorer places, it remains pervasive. But why does boredom afflict some more than others? And what does economic theory have to say about it?

If you go looking in the classics, you’ll find Marx writing about monotony and alienation, but not quite about boredom as we understand it today. Marx’s argument was that capitalism estranges workers by forcing them into repetitive, meaningless labour. Alienation is the loss of purpose, a sense of disconnect between one’s work and one’s self. In this story, boredom emerges from an excess of capitalist discipline, not its absence.

But the Moroccan example complicates Marx’s view. There, boredom arises not from exploitation, but from a lack of market activity altogether: no jobs, no creative outlets, no sources of stimulation. It’s not the monotony of factory work, but the emptiness of exclusion that compels our Moroccan villager to buy a television. Marx’s expectation – that removing capitalist structures would restore meaning and creativity – does not hold in contexts where market activity barely exists.

To be fair, mainstream economics is not much more illuminating. In standard microeconomic models, individuals are rational agents who allocate their time and resources to maximise satisfaction. Boredom is assumed away: if someone is bored, they are expected to seek more rewarding activities. Gary Becker, a Nobel laureate who extended economics into the domain of time use, formalised this idea. He treated time as a scarce resource, something to be distributed among work, leisure and other activities to achieve the highest possible satisfaction. Persistent boredom, in this view, would signal a failure to optimise, an irrational outcome.

Yet the Beckerian model rests on an important assumption: that people have access to meaningful alternatives. This, as the Moroccan villager demonstrates, is often not the case. When jobs are scarce, boredom becomes a structural constraint, not a personal failing; it is not the result of poor planning, but of a poverty of options.

Empirical evidence supports this view. In a recent cross-national study, Sergio Pirla and colleagues found that individuals from lower-income backgrounds reported feeling bored more frequently and more intensely. Their boredom was not isolated: it often co-occurred with anxiety, loneliness and sadness. The findings challenge both Marx’s focus on capitalist monotony and the orthodox economic assumption of rational choice among abundant alternatives. Instead, boredom emerges as a real constraint, one shaped by the same forces that drive poverty itself.

These results stand in sharp contrast to the recent romanticisation of boredom in wealthy societies. I’ve noticed, especially among writers and bloggers on platforms like Substack, a growing nostalgia for boredom. Here is stuntman Riley Harber in April:

Boredom seems to be a luxury now. One we’ve lost. Something the algorithms have expertly taken from us. But I miss it. I miss the slow afternoons, the aimless walks just to walk, the freedom to not respond, not scroll, not improve.

Or textile artist Jordan Storm Louise in February:

In a world that demands constant stimulation, boredom has become something to avoid, something to smooth over. But what if boredom isn’t something to be afraid of, but a doorway?

Or novelist Haley Ahern a year ago:

Humanity depends on boredom and we have pushed it so far out of our lives as if it were a problem to solve. We should not give boredom a negative connotation, boredom is great, boredom is crucial.

This nostalgia, I think, reflects something closer to Thorstein Veblen’s theory of conspicuous leisure. For those with secure jobs and ample resources, the ability to tolerate boredom becomes a status marker, signalling autonomy and self-mastery. Choosing to be bored, or to disconnect, presupposes access to a wide range of alternative activities.

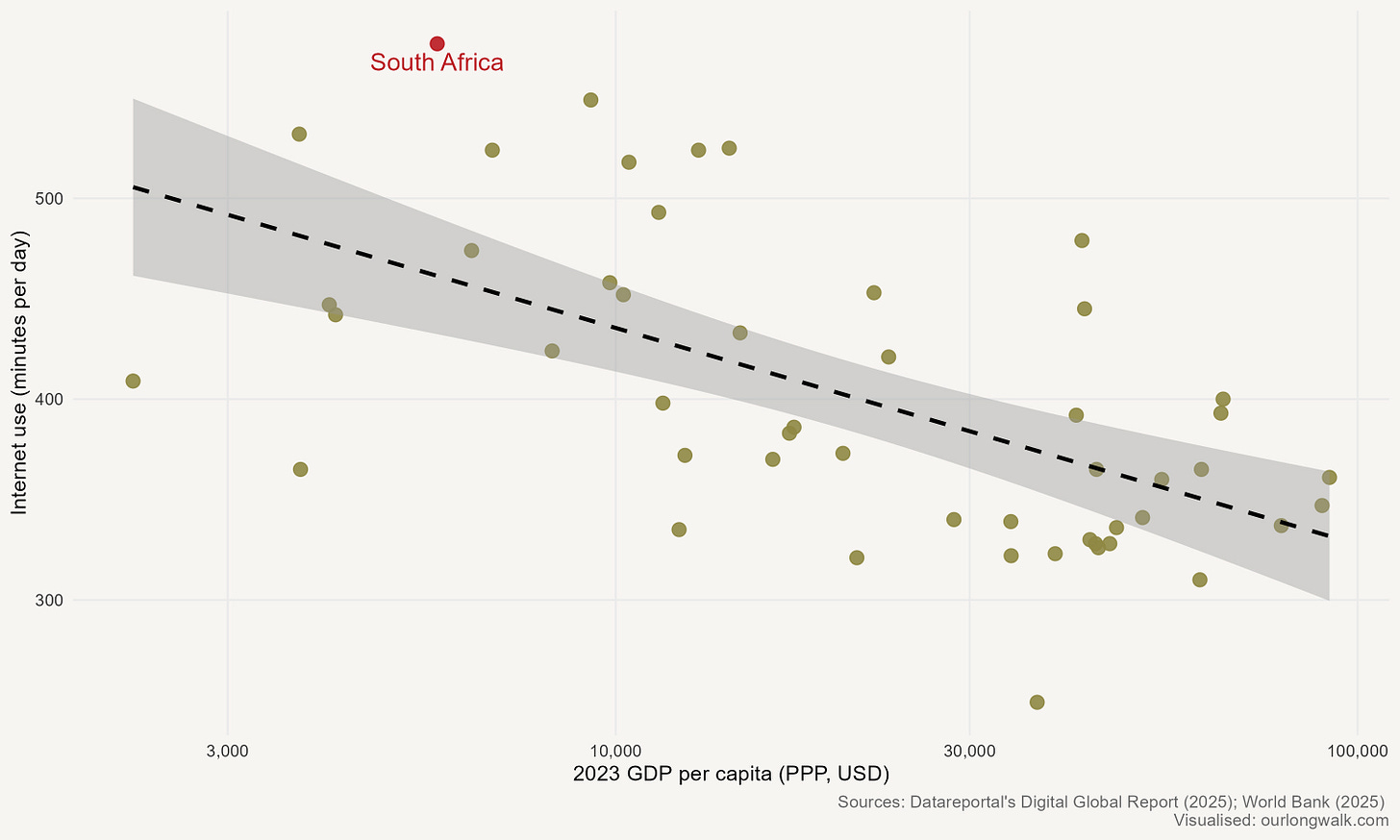

South Africa provides an instructive case. The country is a global outlier in both internet usage and unemployment. The graph above maps daily internet use against GDP per capita. South Africa sits far above the trend line; we spend almost ten hours a day online, significantly more than what income alone would predict. I would argue that this is not evidence of leisure or digital affluence but rather of structural boredom. With youth unemployment above 50% and many communities lacking safe and affordable recreational spaces, the smartphone becomes a lifeline. And it’s not just the young. A friend tells me that his grandmother, now in her eighties and still on the farm, spends her days on her phone. If the battery dies or the connection drops, she feels isolated and adrift. Her story would be familiar to the Moroccan villager.

Critics of social media often focus on the dangers of addiction, misinformation and anxiety. These are real concerns. But in contexts like South Africa, the alternative to being online is often worse: chronic loneliness and social isolation.

The real lesson is that we should be careful what we wish for. Our ancestors did not cherish boredom; they desperately sought ways to avoid it. They told stories, invented games and created rituals precisely because boredom was intolerable. The Moroccan farmer traded scarce food for a screen because boredom was a worse hunger. The generation before today’s grandmothers would have marvelled at the wealth of distractions now available to us, luxuries they could scarcely have imagined in their own time.

For all our recent nostalgia about the lost art of boredom, it is worth remembering that boredom is the historical norm we have tried to escape. Hard times are not just about going without; often, they are about having nothing to do. Good economics should help us solve for both.

This is an edited and translated version of my monthly column, Agterstories, on Litnet. To support more writing like this, consider subscribing for a paid membership. The image was created using Midjourney.

Yes, but... Whilst we shouldn't romanticise it, there is a pretty robust link between boredom and creativity (though it does sometimes come out as destruction).

Spot on Johan! have a look at the the DSTV dishes in townships / here in the Karoo.

And take a family of eight, multiply the time spent of each, versus alternatives - and factor in alternatives that chows less electricity. The only cheaper form of entertainment -amongst adults - is papsak Late Harvest. Would love to hear your take on this scurge, how it came to be systemic, and still ongoing practise; who's behind it, and government's take.