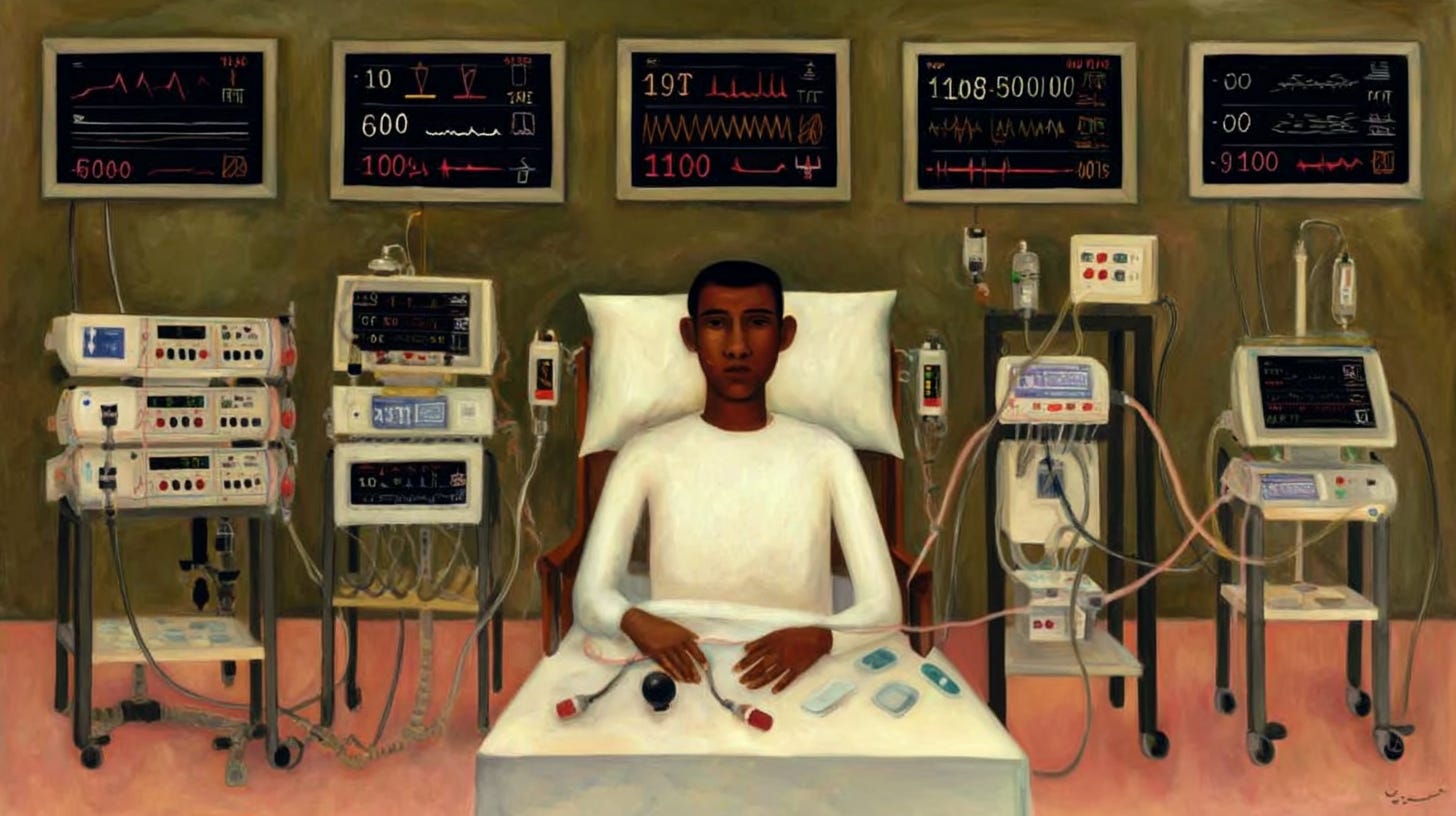

Measuring South Africa's economic pulse

Treatment begins with knowing the true condition

When the Nobel-prizewinning economist Simon Kuznets first created an indicator to measure the economic activity of a country, he was very clear about its shortcomings: “The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income.” GDP – i.e. gross domestic product, which is the total value of all final goods and services produced within the borders of a country within a year – excludes many things we value, such as unpaid work or the natural environment, and includes things we dislike, like military spending. Economists have known this since Kuznets made those remarks to the US Congress in 1937.

Yet, for good and bad, GDP has become the single measure by which we measure a country’s economic performance. For example, compare the GDP per capita of Poland to South Africa over the last three decades. In 1994, Poland’s GDP per capita (at constant 2015 US dollar prices) was $5 262 while South Africa’s GDP was $4 258. Thirty years later, Poland’s GDP was $17 984 while South Africa languished at $5 709. Today, Poles are three times as rich as South Africans, on average, the difference between a 4% and a 1% growth rate.

As it turns out, more money rarely brings more problems – it usually solves them. GDP has survived as a single metric for so long because it is correlated with so many things we do care about. For instance, take infant mortality. The number of South African infants dying per 1 000 live births has fallen by half since 1994, from 48 to 24; in Poland, it has fallen by more than three-quarters, from 13 to 3. Despite its shortcomings, GDP has turned out to be an extremely valuable statistic.

However, there are several new reasons to be concerned about how we measure GDP. The economy is changing. Traditional GDP accounting struggles with products that have a price of zero; using the standard methodology, GDP can only count transactions that involve payments. Digital platforms and free services – such as search engines, social media, open-source software, and, nowadays, Large Language Models (LLMs) – create real value for users but only tangentially register in GDP, for example, in the case of advertising revenue or data sales. GDP really ought to capture ‘consumer surplus’, the difference between what we pay and what we’re willing to pay for a service. Studies that have estimated the size of the consumer surplus for many of our digital products show that it is large and probably increasing.

Quality improvements, too, require a rethink. GDP is based on inflation-adjusted (‘real’) output, which requires accurate price indices to deflate nominal spending. In fast-changing tech sectors, standard price indices often have difficulty capturing quality-adjusted price declines or the benefits of new goods. For example, if the price of a given computing power or data storage capacity has plummeted, but price indices do not fully adjust for the improved quality, real GDP may underestimate growth.

And then there is the shift from tangible to intangible production. In her most recent book, The Measure of Progress, Diane Coyle argues that because of intangible assets like knowledge and health, headline GDP growth can diverge from people’s lived experience. Take the example of technological advances that improve health and longevity, or quality of education. These advances might barely register in GDP, even though they are fundamental to what we would consider as ‘progress’.

Developing countries face additional challenges. As the palaver with Gerrie Fourie’s remarks on South Africa’s unemployment rate demonstrated, the informal economy is difficult to account for in official estimates. By definition, informal enterprises do not file tax returns, and many transactions are in cash or barter. National statisticians therefore lack the usual data (like company accounts or VAT receipts) that feed into GDP calculations. In addition, a large subsistence economy, like the former homelands in which a third of South Africans live, complicates GDP measurement further. The point is that all of the structural measurement problems affecting advanced economies tend to hit developing countries harder, because they often lack the resources to adapt methods quickly.

Resources are indeed often the most serious constraint on GDP accuracy. As Morten Jerven already showed more than a decade ago, many statistical agencies in Africa simply do not have the capacity to deliver quality GDP estimates. I’m concerned that South Africa is increasingly moving in that direction. How is it possible, I’ve asked before, that there is no massive decline in GDP when an economy loses a third of its power supply, as South Africa did in 2023? Or no GDP uptick, when that power is restored in the next year? How is it possible that the Western Cape and Eastern Cape have grown at roughly the same speed over the last decade, as StatsSA’s GDP estimates suggest?

Or take the 2022 Census as an example. A paper presented at the Economic Society of Southern Africa centennial conference in early September concluded unambiguously: “People should not be using the census 10% sample nor the official census statistics.” While these are population statistics errors, not national accounts per se, population figures do feed into GDP estimates as benchmarks for household surveys, into per-capita calculations, and even into the calibration of certain components of national accounts.

The good news is that we are now better equipped to deal with gaps in GDP. Alternative sources of data and techniques – surveys, satellite data, mobile data – can be used to supplement GDP estimates. In fact, collating such data in real time could produce an indicator system that may benefit both business and Government: firms making investment decisions, ratings agencies making risk assessments, the Reserve Bank setting interest rates. Because much of this data is privately owned, however, such a system will require an innovative public-private partnership. Imagine a real-time GDP indicator based on updated info from StatsSA, SARS, Capitec, Absa, Vodacom, MTN, Google, Meta, Shoprite and Pick n Pay, spatially disaggregated. Display this on an official website or app showing the index ticking up or down, perhaps complemented by a few sub-indices (like an employment activity index, an industrial output tracker, etc.) and brief (LLM-generated) commentary. This could do wonders for public engagement: for example, both small and large businesses could consult this source to inform decisions, journalists could use it to explain economic trends in real time, and citizens would have a tangible sense of the economy’s pulse.

Simon Kuznets was right: one number cannot capture a nation’s welfare. But when the patient is in distress, the answer is not fewer measurements – it is better ones, taken more often, from more places, and read with care. South Africa should build a real-time evidence layer alongside GDP, with millions of datapoints from Government and the private sector, collated in partnership and rigorously curated, so that we can understand the economy and the challenges and opportunities within it.

Our economy is sick and time is short. Accurate measurement is where the recovery begins.

PSG’s Big Picture Insights published an edited version of this article in early October. I thank them for their support. The image was created with Midjourney v7.

Your proposal regarding innovative indicators should be seriously considered.