Leaders are not randomly selected

Research on African favouritism suffers from endogeneity issues

A surprisingly large literature has developed over the last two decades that document the ethnic favouritism of African leaders. The story is simple enough: a new African leader comes to power and shifts government resources towards his supporters, typically people of his own ethnic group, building roads, schools, and clinics. Some scholars have shown how foreign donors, notably the Chinese, are also likely to favour the ethnic group of the leader, constructing universities, stadiums or vanity projects in their place of birth.

Take Malawi, for example. The Malawian University of Science and Technology was established by an Act of Parliament in 2012 when the then president of Malawi, Bingu wa Mutharika, secured an 80 million US dollars loan from the Export-Import Bank of China. The university is situated in Thyolo, a tea-growing district about 40 km south of the city of Blantyre and with a mean education level per individual well below the national average during the colonial era. The reason for this strange-seeming choice of location was that it is close to Mutharika’s birthplace and his farm, Ndata, where he was buried in 2012.

Research documenting ethnic favouritism makes one strong assumption: leaders are randomly drawn from the population. In a new research paper published in the Review of Development Economics, Laura Marvall, Jörg Baten, and I show that assumption to be questionable.

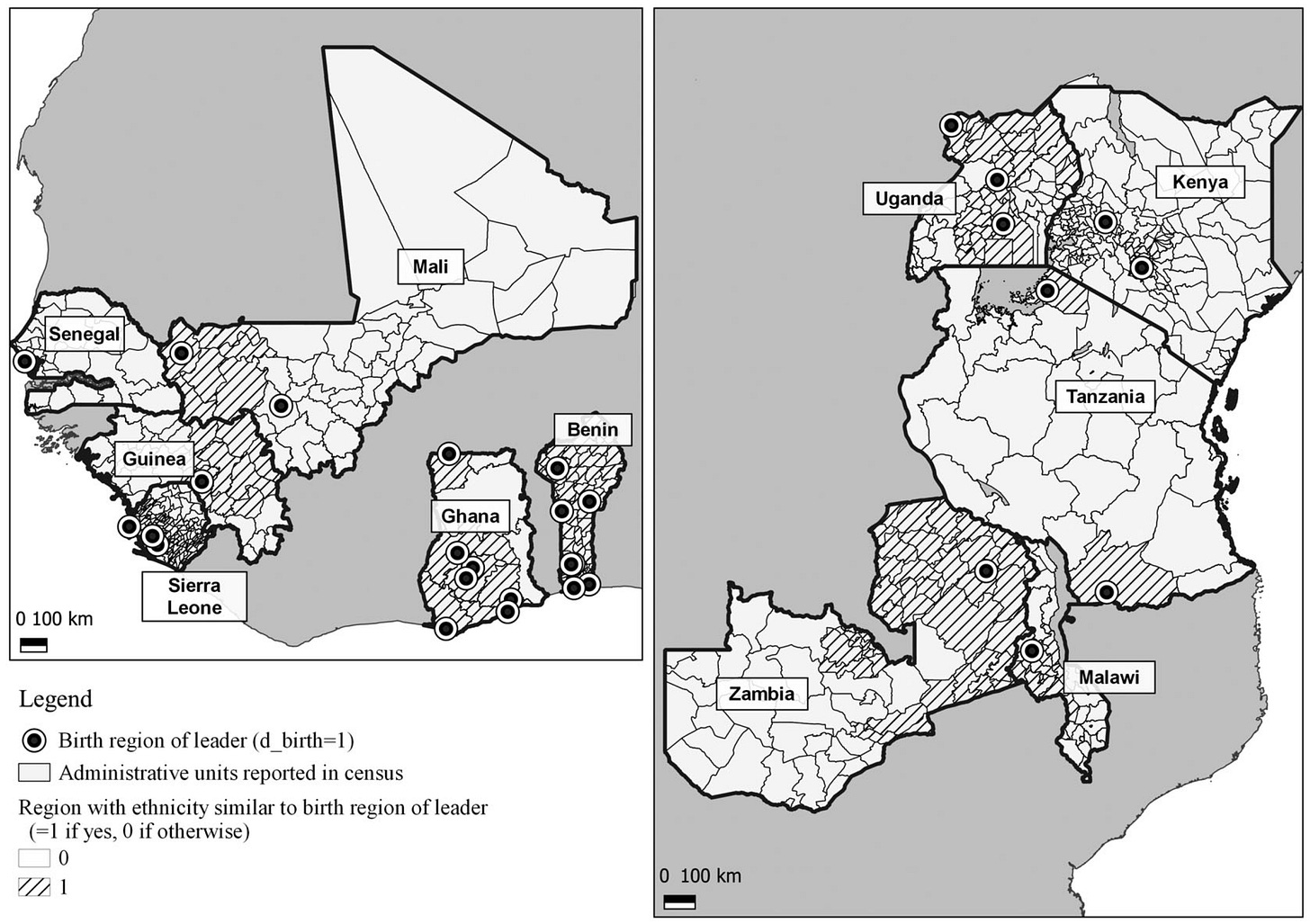

We argue that some regions may have been more likely to produce leaders because of certain characteristics, such as the degree of colonial investment. We focus on how colonial powers selected some regions for more investment than others. To do this, we identify the birthplace of 33 post-independence leaders and examine the differences in colonial education levels from 1930 to 1970. Using census data from the IPUMS International database, we first build a cross-sectional database where the unit of observation is the individual. We then assess the probability of completing primary education depending on whether individuals were born in the same region as the leader before independence and whether they attended primary education before or after independence (defined as from age 6 to 13). Our results show that the individuals in the regions that were the birthplaces of post-independence leaders of our 11 countries had a higher probability of completing primary education, and that the difference was larger during the period before independence.

To test the robustness of our results, we aggregate the individuals into larger geographical units. To do this, we calculate averages of our educational variables: years of schooling, numeracy and the Gini index, capturing the direct input of education, the output of education, and the inequality in education. We then run repeated cross-sections for the birth decades from 1930 to 1970. The results confirm that the leaders of our 11 countries came from regions that were more advanced in terms of colonial education. We also test whether the probability of becoming a leader’s birth region is explained by the degree of colonial education (measured by the early presence of missions in that region). The results show that colonial education increased the probability that a leader would be born in a given region. We focus on the administrative birthplace, but we also consider ethnicity and find similar results.

Our main contribution is to provide a historical perspective on favouritism. We found that the post-colonial leaders of our 11 African countries mostly came from regions with better education in the colonial era, violating the exogeneity requirements of earlier causal interpretations. To be more precise about this, our findings imply that the conventional ‘difference-in-difference’ approach might not be sufficient to deal with the endogeneity issue. This is because that approach depends on the assumption that while areas might be different, they will remain on parallel trends. While this might be true in some cases, it is unlikely to be true for social investments and infrastructure where there is strong path dependence. Wantchekon et al. (2015), for example, show that early education advantages are quite persistent and even increase over time. What this implies is that the parallel trends assumption behind the ‘difference-in-differences’ assumption might be invalid if regions that produce leaders had early advantages. Not only are regions different, but pre-independence trends across regions are not parallel, while post-independence trends are unlikely to be parallel.

Our results caution against the strong causal interpretations that are common in the literature. We find that regions of more favourable education more often produced political leaders than other regions. Leader characteristics influence outcomes today, but leader characteristics themselves are not random. The story of Thyolo in southern Malawi is, therefore, more the exception than the rule.

The broader implication is that researchers using African countries as case studies should be more cautious in their conclusions (or at least acknowledge the mechanism by which leaders are selected for office). Simply because colonial and precolonial-era data is often missing, and advanced econometric techniques allow us to manage without it, is not reason enough to ignore it completely. Development economists who purport to find large effects in the post-colonial period would do well to remember that the colonial (and pre-colonial) formal and informal institutions (especially education) – often unaccounted for in recent censuses or surveys – can account for much of the variation in post-colonial outcomes.

Photo by Joshua Gaunt on Unsplash. The Review of Development Economics paper can be found here.

This is an important finding – not only because it raises doubt about some of the quantitative evidence of ethnic favouritism in Africa, but also because it urges us to think about the policy interests and development models that shaped the thinking of early independence leaders in Africa. Many independence leaders sought to accelerate the late colonial-era development policies (particularly in education), rather than radically alter them, possibly because they came from regions that had been comparatively well served by such policies.

In related work, Elliott Green and I showed other problems with these ethnic favouritism models, and we found that the supposed evidence on ethnic favouritism in Kenyan education is far from robust (see: Simson and Green, 2020, ‘Ethnic favouritism in Kenyan education reconsidered’, Journal of Modern African Studies). This is in part for the same reasons that you discuss – that Kenya’s first President, Jomo Kenyatta, came from the Kikuyu ethnic group, which had the highest educational attainment during the colonial era. By measuring favouritism on the basis of years of primary schooling, which has a hard upper limit, the rate at which Kikuyu primary school attainment grows will slow as this group starts approaching universal attainment. Consequently, the primary schooling gap between the Kikuyu and other ethnic groups looks larger under Kenyatta’s rule than under that of his (non-Kikuyu) successor, and vice versa for the non-Kikuyu groups. These convergence effects, coupled with the fact that the first ruler after independence was often from an educationally-advantaged region of the country, make it quite complicated to model favouritism.

There are also other problems with these models. For example, much of the school construction in Kenya in the 1960s and 1970s was financed and undertaken by local communities rather than the central government, so the rate at which primary schooling expanded was in large part demand-driven. You could argue that President Kenyatta favoured this model because it served the interests of the Kikuyu (who were better placed to make schooling investments), but this is a rather far-fetched notion of ethnic favouritism, and one can make a strong developmental case for allowing such self-financed, demand-driven service expansion, even if it is regressive. In fact, I think the ethnic favouritism literature on Africa would benefit from a more traditional study of the distributional consequences of different policy regimes, and how the background of politicians, and the constituencies they represent, shape these policy preferences.

Thanks for sharing, and will definitely read the longer paper.

What would be interesting would be the factors that led to colonial social investment within a particular area i.e. are there other pre-colonial institutional factors which led to a larger concentration of missionaries within an area, which then led to more educational institutions, which then led to more post-colonial leaders.