Is African inequality inevitable?

GUEST POST: High skills premia make African firms less competitive and mean that African governments will struggle to hold on to their most skilled employees

This is a free post from Our Long Walk, my blog about South Africa’s economic past, present, and future. If you enjoy it and want to support more of my writing, please consider a paid subscription to the twice-weekly posts, which include my columns, guest essays, interviews, and summaries of the latest relevant research.

Inequality in Africa is back on the academic agenda. While the development discourse of the 1990s focused on poverty and deprivation, scholars and policy researchers are rediscovering disparities within African societies. An undertone in many of these studies is that something is awry; whether through political patronage, elite capture, or neoliberal privatisation bonanzas, the gains from the continent’s recent growth have accrued unfairly to the very richest.

While I admire efforts to bring African country experiences into global literature on 20th-century inequality paths, existing studies have typically grasped political economy explanations for the surprisingly high levels of income inequality found in many African countries. Researchers have given surprisingly little attention to the arguably most obvious driver of income inequality in Africa – relative poverty itself. In a world where the highest skilled are highly mobile, salaries for certain professions are, in effect, set internationally. Consequently, rising between-country inequality drives within-country inequality in poorer countries.

These reflections draw from my casual observations of African labour markets, over a decade of working for international organisations across West and East Africa. I have long struggled to square popular (and academic) perceptions of inequality, with my impressions of the characteristics of Africa’s high earners – characteristics which offer clues to the drivers of the top 1% income share.

My impression is that beyond the expatriate community itself, among the citizens of Sierra Leone, Tanzania or Benin, for instance, the highest income earners are typically employees of international organisations, multinational corporations, NGOs and banks. A smaller share of this income elite are politicians or top government officials, and an even smaller sliver are owners of larger firms. This income elite is typically highly educated, and many of its members have studied or previously worked abroad. Many hold a second passport or have other outside employment options. In countries with annual income per capita around the thousand dollar mark, such employees are paid many multiples of the average national wage, for the obvious reason that they would not otherwise stay.

This is a long-winded way of saying that for a certain segment of Africa’s labour force, the threat of brain drain pushes the skills premium upward, beyond what it would be if competition for skills was solely domestic. Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest rate of high-skilled emigration in the world and the rate has risen since the mid-1990s. By one 2002 estimate, 6% of African-trained doctors were working in the U.S. healthcare system alone. In recent years, Uganda’s Nurses and Midwives Union, with governmental support, have brokered deals to send thousands of Ugandan-trained nurses to Britain and the Middle East (which also reveals the ambivalent position that African governments have taken to skilled labour migration). Recent research also shows that although skills premia have decreased in Africa over the course of the 20th century, they still remain higher than elsewhere in the world.

A less studied feature of Africa’s skilled labour migration is its intra-African dynamics. Where skills are in particularly short supply, skilled workers are often recruited from neighbouring countries – Ghanaian managers run UN departments in Sierra Leone, Ugandan and Kenyan accountants staff organisations in South Sudan. NGOs and international organisations often institutionalise a two-tiered salary structure, where internationally recruited staff earn a substantial premium relative to those that are recruited domestically. Such organisations identify talent internally among their nationally recruited staff, and the most talented employees multiply their earnings when promoted to an international role in a neighbouring country. Thus skills scarcities in one economy inflate the skills premium in the neighbouring one.

Furthermore, this skills premium inflation could, in theory, affect wage dynamics at large. If nurses are at risk of migrating, but teachers are not, the wages required to retain the nursing staff may nonetheless but upward pressure on teacher salaries. Unions are unlikely to look sympathetically on government salary scales with marked wage differentials across ministries.

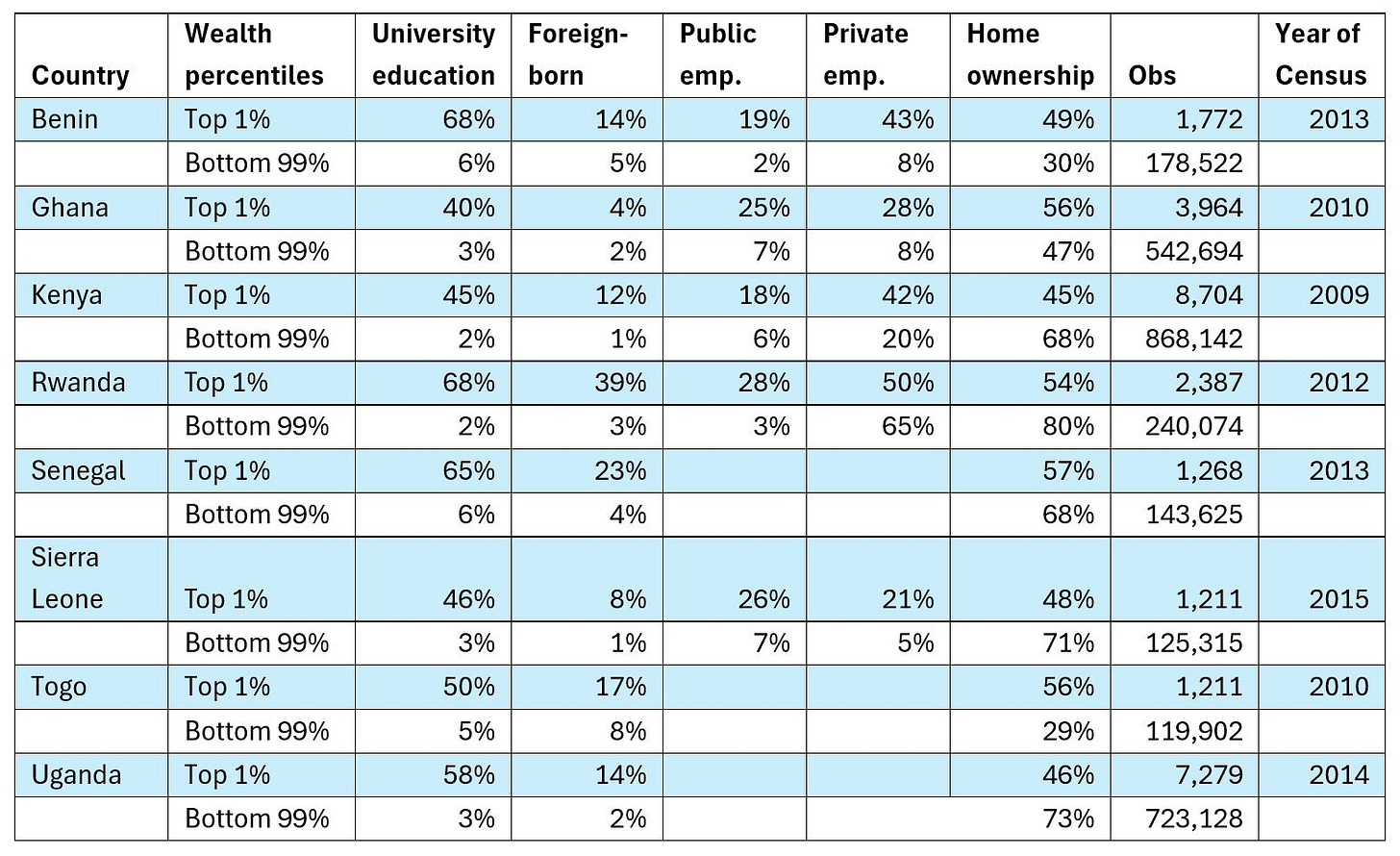

Does existing data support this conjecture? Table 1 provides some simple, suggestive evidence. It uses recent census data for eight African countries to construct socioeconomic indices, based on asset ownership and wealth characteristics at the household level. It then compares the characteristics of the household heads in the ‘top 1%’ households, to those of the bottom 99%.

What characterises the top percentile? Unsurprisingly, this top strata is highly educated. But the sheer size of this educational gap is staggering. Across these eight countries, 40-70% of the top percentilers are university educated, relative to 2-6% for the bottom 99%. Most of the top 1% are formal sector employees, and with one country exception, a larger share of work in the private than the public sector (which should throw some suspicion on a pure public sector premium explanation for high inequality).

A substantial share of the top 1% are foreign-born, suggesting that many African countries rely considerably on foreign high-skilled workers. Another interesting statistic is that only about half of these top percentilers own the home they live in. Some may, of course, own other assets of note, but it is likely that employment income remains the main source of income for many in this bracket. In sum, these simple descriptives suggest that income inequality is, in part, a function of the pay packages commanded by skilled employees in private firms and organisations.

This has a number of hypothetical (and testable) implications. Firstly, for historians, this should have a familiar ‘kicking away the ladder’ ring to it. Skilled labour markets are more globalised today than they were a century ago, and global income gaps have risen. Consequently, it will be relatively more expensive for Uganda to hold on to its mining engineers and corporate lawyers than it was for Finland, for example, when it was catching up with Western Europe.

It also leads to a Kuznets-style inverted-U prediction, albeit with a different set of drivers in mind. As countries develop, more of the highest human capital is supplied domestically rather than internationally, and thus inequality is increasingly internalised. The highest skilled workers, previously expatriates on international contracts who were unlikely to be captured in the sources that underlie inequality statistics in the first place, are now nationals who are more visible in national statistics (and more noticeable politically).

Furthermore, this would imply that country characteristics that influence opportunities to migrate would accentuate wage inequality. Open economies with a history of migration, some internationally ranked universities, and where English is widely spoken will face stronger international competition for their skilled workers. African-trained doctors in the US, for instance, originate almost exclusively from Nigeria, South Africa, and Ghana.

Are these dynamics all bad? Literature on the brain drain has pointed to mixed effects. If the outflow of the educated is relatively small, the remittances, skills and networks that migrants develop can, on balance, be positive for the source country. And we probably need not worry too much if inequality is rising simply because expatriate workers are being replaced by highly skilled nationals. But high skills premia clearly make African industrial enterprises less competitive, and mean that African governments will struggle to hold on to their most skilled employees, which compromises their ability to provide public services.

Inequality is an emotive topic. For many, Africa’s top 1% conjure up images of Kenya’s Members of Parliament, with salaries of $5,600 a month, or the private fortunes of Aliko Dangote in Nigeria or the Kenyatta family in Kenya. But the capital incomes of Africa’s highest net worth individuals are unlikely to feature in any inequality statistics in the first place, and lawmakers, which typically number in the hundreds, make up an insignificant number of the top 1% in any country. The median member of the African 1% may well be a project manager or lawyer working for an NGO or small trading firm who owns a family home in the suburbs of the capital city. To better understand income inequality in Africa, we may gain more from a return to some good old-fashioned labour economics and models that explain why private firms and non-governmental organisations pay their skilled workers the way they do than complex political economy models.

‘Is African inequality inevitable?’ was first published on Our Long Walk. The image was created with Midjourney v6.

A brain drain seems inevitable, given work by Michael Clements cited in The Time Travelling Economist. But most of those getting educated will stay. And those who leave will send back remittances. Not all bad

It's not inevitable, however, many of the countries in sub Saharan Africa are in the middle income trap and cannot aspire less inequality without policies that put growth before inequality.