Inflation deliberation

As South Africans wait for a new inflation target, it is worth remembering that it is not only the Reserve Bank and Treasury that is responsible for low inflation

South Africans are waiting for an announcement on a new inflation target. As News24 reports, the Reserve Bank and National Treasury have issued a joint statement confirming that technical work is nearing completion and that the finance minister will announce the framework once the institutions agree on any changes to the current band. That announcement may arrive at any moment, but even if the headline number shifts, the deeper question remains: what makes an inflation target succeed?

The temptation is to treat the target as a purely technocratic number, set at 3, 4 or 5 percent, whose precise level will, almost mechanically, deliver price stability. But the economy does not work like that. What a country targets matters less than what people believe will happen and how they think policy will respond when shocks arrive. This is the central insight from Harvard economist Stefanie Stantcheva’s work on beliefs and policy: macroeconomic tools operate through the stories people tell themselves about the economy. If workers expect prices to rise faster, they bargain defensively; if firms expect regulators to pass through cost shocks, they mark up more quickly; if households expect higher rates to linger, they postpone investment. A target anchors behaviour only when the story is credible, comprehensible and widely owned.

South Africa’s existing framework of a 3–6 percent band has long aimed to balance flexibility with discipline. In practice, the midpoint of 4.5 percent became an informal focal point and, over time, too many prices, from administered tariffs to wage norms, settled in the upper half of the band. That is why narrowing and lowering the target has intuitive appeal. A wide band invites discretion, while a lower and clearer anchor can concentrate minds. Both the Reserve Bank and National Treasury recognise the long-term costs of a wide band and the distributional harm of chronically high inflation, which is why a new target is likely soon.

The timing is propitious. Inflation has decelerated, which gives policymakers an opening to lock in credibility rather than chase it from behind. Lowering the target when inflation is falling is an attempt to stop the next cycle from re-entrenching high-inflation norms. Some fear that a lower target automatically means higher for longer interest rates. That is not a law of nature. If a lower target re-anchors expectations, and if unions, regulators and firms adjust their rules of thumb, market rates can fall sooner and by more because the central bank faces less risk of a renewed flare-up. The level of the policy rate is not the point; the credibility of the reaction function is.

Stantcheva’s work also shows how to build that credibility. Communication matters because people’s policy views are shaped by narratives about fairness and causality: who they think benefits from inflation and who they think is to blame when prices jump. In surveys across countries, many respondents attribute inflation not to supply constraints or energy shocks, but to employer behaviour. That employers are often price takers is seldom considered. The practical implication is clear. Translating the target into a widely understood social contract is as important as the number chosen. The message cannot be that inflation is a statistical artefact to be optimised by technicians. It must be that low inflation is a fairness policy that protects real incomes, lowers borrowing costs and rewards long-horizon investment.

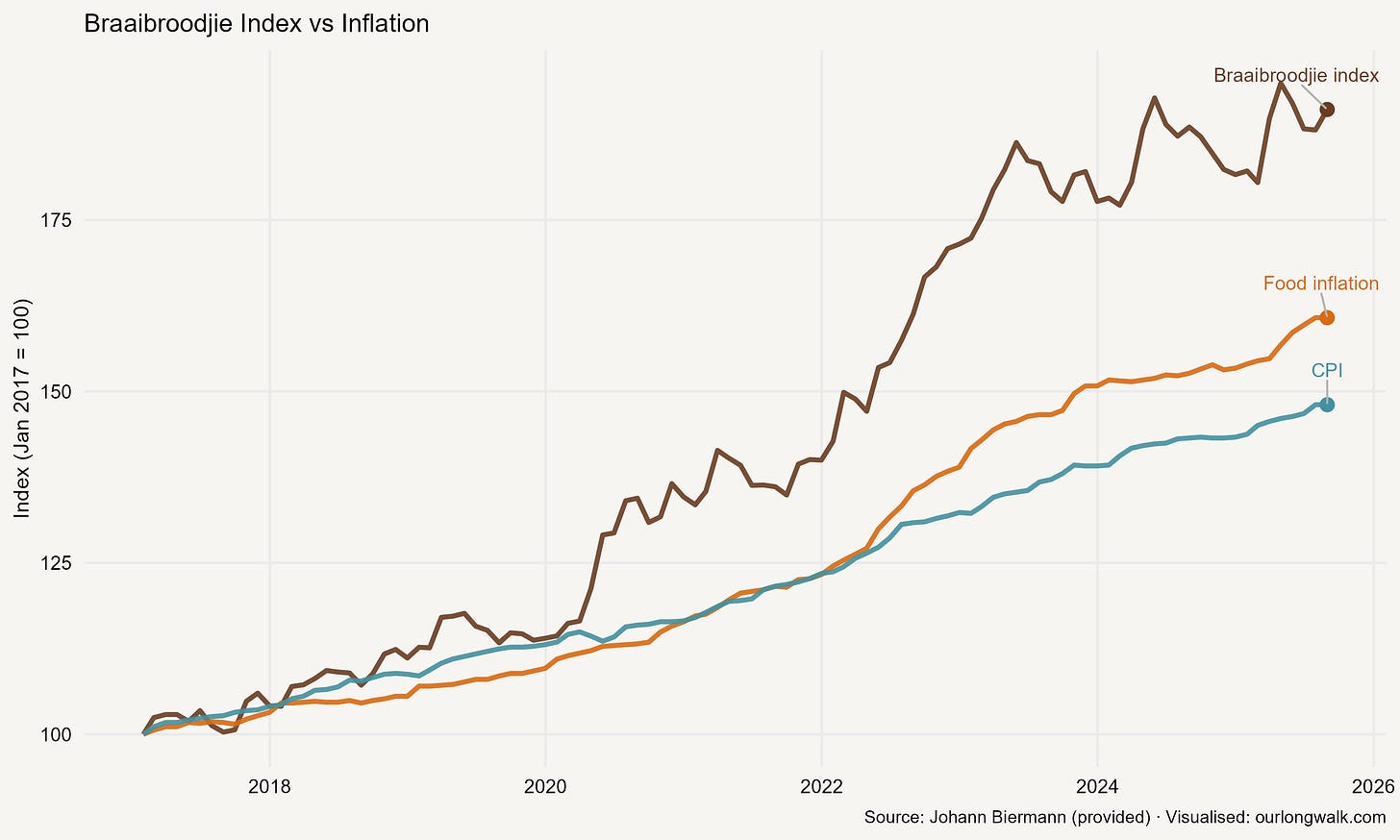

If policy must meet people where they are, it must also recognise that they are not all in the same place. Inflation’s burden is unevenly shared. When food, fuel and administered prices lead the cycle, poorer households, who spend a much larger share of their budgets on those items, face an effective inflation rate above the headline. That inflation inequality erodes real wages fastest where buffers are thinnest and can weaken support for the anchor. Government should therefore communicate in terms people recognise. Johann Biermann’s braaibroodjie index is a useful example: the cost of bread, cheese, tomato, onion and chutney has risen faster than both food inflation and headline CPI since 2017 (see the figure). Tracking such everyday baskets against the target helps people judge whether the prices that matter to them are moving in line with the anchor.

Given this, what should the new anchor look like? First, it should be simple, narrow and symmetric. Second, communication should make explicit how supply shocks are handled: the central bank will look through temporary spikes but lean more forcefully if second-round effects appear in wages and administered prices. Third, and crucially, every institution that sets prices the public cannot avoid, including electricity and municipal services, public transport fares, health-care reimbursements and excise taxes, should publish inflation-consistent medium-term paths. When Eskom or a metro proposes a double-digit tariff increase, it should explain why this does not undermine the inflation anchor and how the increase will be offset elsewhere. If Treasury and the Bank are asked to do the hard work of anchoring expectations, other arms of the state cannot behave as if they operate in a different macroeconomic climate.

Consider wage setting. A lower target is a coordination device for employers and unions. If settlements track the upper end of a wide band, inflation becomes self-fulfilling. If settlements are indexed to a lower, credible anchor, real wages become more predictable and firms are more willing to invest. That requires trust that the anchor will be defended. The same logic extends to competition policy and market structure. In concentrated sectors, firms can pass on cost shocks more easily and may do so pre-emptively. A credible low-inflation regime therefore needs a competition authority that is vigilant about collusion and opportunistic pricing during supply squeezes, and regulators who resist cost-plus rules that socialise inefficiency.

Critics often ask whether a lower target will choke a weak economy. The honest answer is that it depends on how we do it, and on the level of country risk. If a new target arrives without a roadmap, and if the rest of government acts as if the anchor is someone else’s problem, interest rates may have to stay high to force compliance. Even with a careful plan, borrowing costs will not fall for long if South Africa’s risk premia are still elevated. Investors compare risk-adjusted returns across emerging markets. Unless fiscal sustainability improves, politics stabilise and institutions regain credibility, the economy’s ‘neutral rate’ – the rate consistent with stable inflation and normal growth – will sit above the target midpoint, keeping real rates uncomfortably high. The route to lower rates therefore has two lanes. One is credible disinflation. The other is credible macro management: predictable budgets, reform of state-owned enterprises, stable and transparent rules, and fewer policy zigzags. Countries such as Israel in the 1990s and Chile in the 2000s brought inflation down and kept rates down because they paired the target with institutions that squeezed risk premia.

What should South Africa aim for now? A lower, narrower, symmetric target, backed by fiscal and regulatory commitments and explained in plain language, gives the best chance of reducing both average inflation and the spread across households. We should judge success by more than the headline CPI. Inequality in inflation should shrink. Everyday baskets should move with the target. The braaibroodjie index is a simple test: if it rises more steadily and in line with the target, people will believe the anchor is real in the prices that matter to them. Investors will believe it too if country risk premia and sovereign spreads narrow. When that happens, households, firms and lenders will set wages, prices and lending terms in ways that reinforce the anchor. The Reserve Bank and National Treasury can set it and defend it. Bringing down the risk premia, and with them interest rates, depends on the whole of government.

An edited version of this article was published on News24. Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. The image was created with Midjourney v7.