Hamba kakuhle, totsiens, goodbye

Why emigration can be good for South Africa's economy

Nick is thirty. He has spent the past few years in monitoring and evaluation, helping turn complex projects into clear evidence about what works. When an international agency invited him to take up a position in Amsterdam, he hesitated. After long conversations with his wife and thoughtful discussions with his parents, he decided to go. Friends reacted with concern: South Africa, they said, cannot afford to lose people like him.

But Nick’s reply is more measured than emotional. He responds that he’ll maintain links with South Africa: he’ll visit his family at least twice a year and hopes to connect his business contacts to those in his newly adopted country. And he’d love to return home one day to retire, he says.

Nick is correct. A recent paper in Science by Catia Batista and colleagues show that high-skilled emigration does not always drain talent from the countries people leave. Under the right conditions, it can increase skills at home, and it can also bring money, ideas and networks back. “We now have empirical validation of the theoretical argument that new high-skilled migration opportunities can increase, rather than decrease, the overall stock of educated workers” in the countries they leave, the authors argue.

It works like this: When the chance to work abroad raises the payoff from education, more people study. Not all of them will emigrate. As a result, the number of skilled professionals in the home country can grow. The paper offers strong examples. When the United States expanded nurse visas in the early 2000s, enrolments in nursing schools in the Philippines jumped. More nurses left, but even more were trained, leaving the Philippines with more nurses overall. In India, a rise in H-1B visas encouraged more young people to study computer science. Many went abroad, but many stayed, and the country’s IT sector grew with them.

Education is just the first part of the story. Migrants abroad usually earn more, and they send money home. Those remittances often pay for siblings’ schooling or small businesses. Diaspora communities also build bridges: they connect firms at home to new markets, new investors and new technologies. Some migrants return after years abroad, bringing experience and savings with them. The authors point to research that shows that firms linked to returnees often perform better, and scientists who come back tend to lift the productivity of their colleagues. Even in health – the area most often cited as a risk – the review finds little evidence that emigration worsens outcomes. Quite the opposite: norms and knowledge often flow back in ways that strengthen care. Emigration, the authors are careful to argue, can help countries of origin, but much depends on whether they have the capacity to train more people, attract investment and work easily across borders.

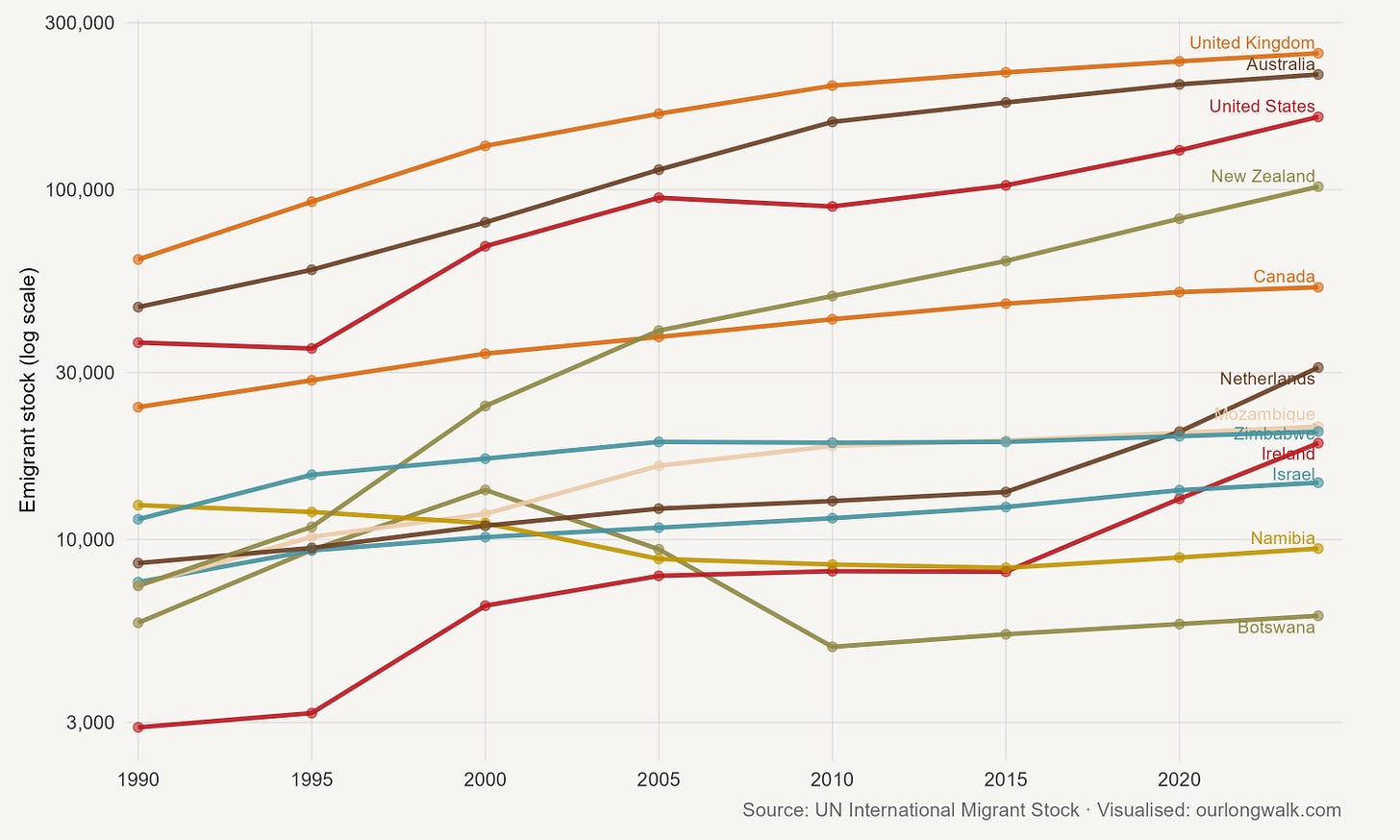

South Africa’s own migration record gives the claim local texture. The figure below tracks South Africans abroad since 1990 on a logarithmic scale. Three phases stand out.

The first phase, in the 1990s, was one of change. The political transition brought many exiles home, which reduced the South African-born populations in places like Namibia and the United States. At the same time, South African companies pushed into the rest of Africa and skilled workers took up posts in Botswana and Zimbabwe. Stocks there rose from small bases through the early and late 1990s. This two-way movement is often missed in debates that dwell only on the OECD.

Around the turn of the century, South African emigration figures began to climb, reflecting the country’s opening to the world, the pull of better opportunities abroad on the back of high growth rates in the rich world and, perhaps, unease about political, economic and social change at home. Newspapers ran ‘brain drain’ headlines; commentators tried to put numbers to the outflow, not only in headcounts but in the loss of scarce skills. Care is needed when reading those numbers. Statistics South Africa stopped collecting emigration data in 2004, so the best evidence comes from destination-country stock counts – like the ones I’ve used above – which show a continuing net outflow through the 2000s and signs of acceleration thereafter.

One feature of this era is the move to the English-speaking world. The United Kingdom and Australia dominate, their South African communities rising steeply in those years. Each now hosts well over 200,000 South Africans. The United States also grew, dipped briefly after the global financial crisis, and then resumed its climb. New Zealand stands out visually: from a tiny base to around 100,000 today. Canada shows steady, reliable growth across the whole period.

The third phase, from the 2010s onwards, is one of consolidation with a few new surges. Growth in the UK and Australia slowed but continued. The Netherlands, largely flat for two decades, grew quickly after 2015. For Afrikaans-speakers, the language is a draw; Dutch cities also offer stable governance, professional opportunities and family-friendly life. Ireland’s growth is more modest but still notable: up in the early 2000s during the boom, flat around the global crisis, then rising again into the 2020s.

The question is how South Africa turns outward migration into national advantage. The country has some of the key ingredients: strong universities, research institutions able to collaborate internationally, and firms already integrated into global markets. Policy can strengthen these channels. Embassies and consulates could work actively to link South African professionals abroad with organisations at home. Returning migrants could be supported through easier recognition of qualifications, simple re-entry into public service, and modest tax relief during the transition back. Regulations could also be adapted to make it easier for South Africans to live locally while working for foreign employers, keeping earnings and skills in the domestic economy. And why not use international sports events – the Springboks at Twickenham, the Proteas at the SCG – to advertise homecoming campaigns?

These initiatives would mark a shift from treating emigration as a loss to managing it as circulation. That is what the review makes clear. Short-term disruptions are real when hospitals or firms lose key staff. But the medium-term gains from remittances, trade, investment and returning expertise can be larger, especially in countries with the capacity to train and to absorb. South Africa is one of them.

Nick’s departure will not sever his ties with South Africa. In Amsterdam, he will deepen his skills, expand his networks and gain perspectives that no local job could provide. Perhaps, in a few years, when kids arrive or parents grow older, the pull of home will prove irresistible and he will return with fresh expertise and capital to invest. Perhaps he will remain abroad, sending back remittances and opening doors for South Africans who follow. Either way, the choice is not between losing him or keeping him. The real choice is how South Africa chooses to remain connected to him once he has gone.

An edited version of this article was published on News24. Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. The image was created with Midjourney v7.

https://businesstech.co.za/news/business/841217/south-african-companies-sound-the-alarm/?utm_source=newsletter