Globalisation, recurring

GUEST POST: A new view of the global economy

Globalisation is on its deathbed. What ails it? A short list of afflictions include Brexit, the resurgence of industrial policy, tariffs and retaliatory tariffs, the demise of the WTO appellate body, capital controls to limit financial instability, and border walls to limit immigration. These policy choices reflect a broad challenge to the neo-liberal consensus of the recent past.

But reports of globalisation’s demise have been greatly exaggerated, as they often are. Indeed, this is not the first time globalisation has fallen flat. My new book ‘One from the Many: The Global Economy since 1850’ (Meissner, 2024) explores the ups and downs of globalisation over the long-run. I assert that global integration is on a long-run, inexorable rise, but glitches and setbacks can arise intermittently. Trade, capital flows and migration are driven by the human desire for progress and to improve the standard of living. Globalisation promises to deliver such gains but it also carries side effects which must be recognised.

What is globalisation?

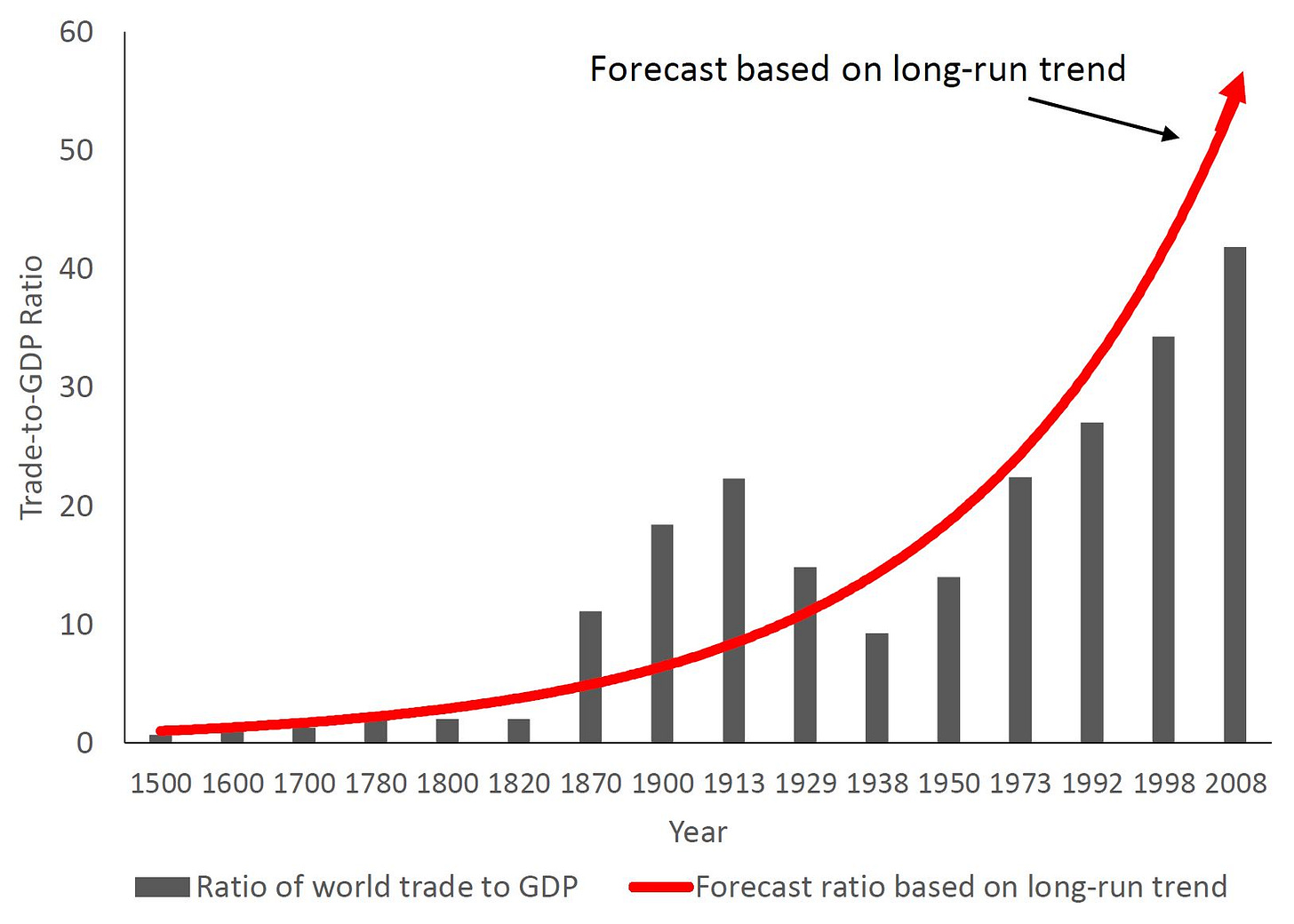

To measure globalisation, economists typically focus on international trade, cross-border capital flows and international migration. Standard indicators of global market integration are the share of global trade in total output, the ratio of global foreign assets to total wealth or income and the share of foreign-born in the local population.

After decades of research, economic historians have been able to provide the data required to piece together the long-run story of globalisation. My book starts by presenting these indicators of integration over the long run in a systematic and comparable way. Figure 1 shows the level of integration in world commodity trade from 1500 to 2008.

Before the mid-19th century, some trade in commodities occurred. Due to high transportation costs and many other barriers to integration, the overall level of global integration remained low relative to total economic activity.

From about the mid-19th century until 1914, standard indicators rose to new heights. The period from the mid-19th century up to the 1870s saw a massive rise in integration. However, from 1880 until 1914 the pace of integration decelerated, especially in the most economically advanced economies.

Between the world wars, from 1919 until 1939, globalisation suffered many setbacks. While the 1920s appeared to herald a return to normalcy, the 1930s featured a global trade crash, moribund international capital markets and much more limited migration.

After World War II, trade made a strong comeback, while cross-border capital flows and labour movements trended up, especially after the 1970s. The 1990s and early 2000s, were declared an era of hyper-globalisation.

What drives globalisation?

In addition to exploring the data, I also examine the forces driving globalisation. In the 19th century, declines in the costs of international transactions promoted rising integration. These declines included improved methods of shipping, extension of railways, the telegraph network, lower tariffs via liberalisation, a financial system with global reach, the gold standard which fixed exchange rates for much of the world, and a many other micro-level trade costs which mattered.

International trade in wheat, cotton, rice and other commodities narrowed the once-large price gaps between markets. Finished goods and machinery became progressively cheaper to ship, bringing gains from variety to consumers and producers alike. Capital flows rose as an internationally oriented financial system based in London offered new investment opportunities many economies of the world were eager to take. Meanwhile, the pull of New World opportunities and the push of population and economic pressures in Europe drove migration to new heights. When tariffs began to rise in the late 19th century, integration decelerated. Backlash to international migration was already apparent as in the US Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Global financial crises like the Baring crisis of the early 1890s and others stymied trade in goods and assets for years.

In the interwar period, economic dislocation led to great uncertainty. This limited trade and financial flows. The New World, especially the USA, implemented a range of new limits on immigration, but the attraction to immigrate had also declined. Wages had risen in traditional sending areas while the economic opportunities of receiving economies were diminished. In the 1930s, a host of capital or exchange controls and tariffs arose with the goal of defending the balance of payments and protecting market access from outside competitors. The Great Depression dealt a huge blow to globalisation.

By the latter half of the 20th century, the world system was increasingly governed by international agreements and institutions, including the GATT/WTO, the Bretton Woods institutions (IMF, World Bank, Paris Club), the EEC/EC/EU and other regional trade agreements that began to cover capital flows and labour standards. As communication costs plummeted and air travel improved, global offshoring intensified, and capital flows mushroomed.

As noted above, by the 2010s, many indicators of globalisation had flattened largely due to policy changes and the perceived costs of integration. These include vulnerability to financial crisis as the 1990s showed in East Asia and geo-strategic worries about supply chains.

How does globalisation matter?

Throughout ‘One from the Many’, I try to use economic theory to help the reader better understand the process of globalisation. In the first wave of globalisation, integration tended to promote income convergence among the small-open economies in Europe, Japan, and the European settler economies as trade theory might predicts.

Another large group of economies including India, China and many in Africa and Latin America missed the convergence boat. Extractive colonisation and governance issues meant these economies could not fully reap the gains from the underlying technological changes. Financial crises plagued the world system, then as now. The USA, Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Greece, Spain and Portugal all suffered from excessive financial volatility due to their mishandling of foreign capital inflows.

World War I heightened awareness that foreign sources of supply and demand were not immune to geo-political conflict. Moreover, the problem of financial instability only got worse in the 1930s. By then, many nations concluded that the global economy carried too many risks. Isolation and self-reliance ensued. The Great Depression is studied as a global financial shock replete with financial crises reminiscent of modern theories of financial instability.

Following World War II, it took a long time for nations to embrace the spirit of liberalisation despite the best efforts of a US-led international epistemic community that touted the benefits of integration. Trade increasingly became a matter of intra-industrial trade. By the 1990s, leaders across the globe had become more convinced of the gains from integration and economic convergence resumed, bringing much of Asia onto a modern growth path. Eastern Europe, emerging from its decades behind the Iron Curtain, also enjoyed stronger growth in many cases. Few parts of the world were untouched by the new flows of capital, the movements of people and the ICT revolution of the late 20th century. Those economies which had maintained the pre-requisites for modern economic growth established by theory (human capital, property rights, low corruption, constraints on the executive) benefitted the most. Still, economies in Latin America and Africa experienced the global commodity boom and the rise in demand for their commodities.

Where are we headed?

Globalisation and integration are not always smooth sailing. Therefore we must never ignore the political economy of globalisation. Dani Rodrik suggests that if nations choose more integration, they must either give up on democracy or self-determination. The case of Greece during its financial crisis of the 2010s is illustrative. Greece relied on international financing and enjoyed strong democratic norms, but it nearly crashed out of the European Monetary Union when capital flows reversed, and the global financial crisis engulfed the economy. In the end, the government was forced to implement the fiscal austerity and institutional reforms mandated by international institutions like the ECB, IMF and the ‘Troika’. Greece is not the only economy to have suffered the downside of globalisation and liberalisation and also lost some of its sovereignty along the way.

Still, many countries have gained, on balance, from the global economy and have faced nothing so extreme. What makes the difference? Nations that can capably govern themselves and successfully implement policies to compensate those groups that gain relatively less have always stood to gain more from globalisation. International cooperation and adaptation are key considerations. Economies must always choose the amount of integration they can manage effectively.

The bottom line

Based on the analysis of the long run of history using data and theory, my bottom line is that globalisation will survive this temporary ruction. International competition can promote improved governance and the ability to better manage globalisation. Economies are often willing to undergo such structural transformations because the ostensible gains from integration are large. The urge to improve and progress, wholly instinctive to humans, is not easily repressed. The short-sighted strategic vision of isolation and autarky always presents a siren call and can be a political winner. However, the history I explore in my book shows that with a long-enough time horizon, the survival of globalisation is almost certainly assured.

‘Globalisation recurring’ was first published on Our Long Walk. Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. As an Amazon Associate, I may earn from qualifying purchases. The image was created with Midjourney v6.

Great article. Very relevant, not only in Africa.