Gini confusion

Redistribution is not the remedy to South Africa's economic malaise

Michael Sachs, a former senior Treasury official and now academic at Wits University, is adamant: South Africa cannot grow without large-scale redistribution. In a new report, he acknowledges, correctly, that redistributing income through taxes and public spending has reached its limits. Yet instead of taking the next logical step and focusing on growth as the way out of South Africa’s economic impasse, Sachs circles back to old arguments for more redistribution. Why are we having this debate again?

Sachs argues that despite decades of expanding public services and social grants, South Africa remains trapped in stagnation, high unemployment, and deepening exclusion. He criticises the current consensus, which focuses on enabling markets and fixing the state, for lacking what he calls ‘a transformative vision capable of shifting the underlying structures of economic power and production’. Sachs insists that tackling these challenges requires a fundamental shift in strategy: away from income redistribution and towards the redistribution of assets. As he puts it, ‘inequality and exclusion are the binding constraints on growth’, and calls for ‘a new political economy strategy – rooted in asset redistribution and capability development – that connects investment with transformation and redefines the trajectory of South Africa’s development’.

Sachs is not wrong to say inequality remains severe or that South Africans are desperate for meaningful economic improvement. But on almost every substantive question, his analysis stumbles. It fails to account for the ways inequality has changed, for the actual drivers of poverty, and for the lessons from other countries that have managed to lift millions out of deprivation.

To begin with, Sachs clings to a narrative of persistent racial inequality, arguing that ‘investments in white education and social privilege over many generations (and the concomitant destruction of black institutions and capabilities) are transmitted through households’. This, he says, is the real story of post-apartheid inequality. But his citation, ‘See Fruend; also World Bank and a thousand other papers’, is little more than hand-waving. Among those ‘thousand papers’, none seems to have pointed out what recent evidence makes painfully clear.

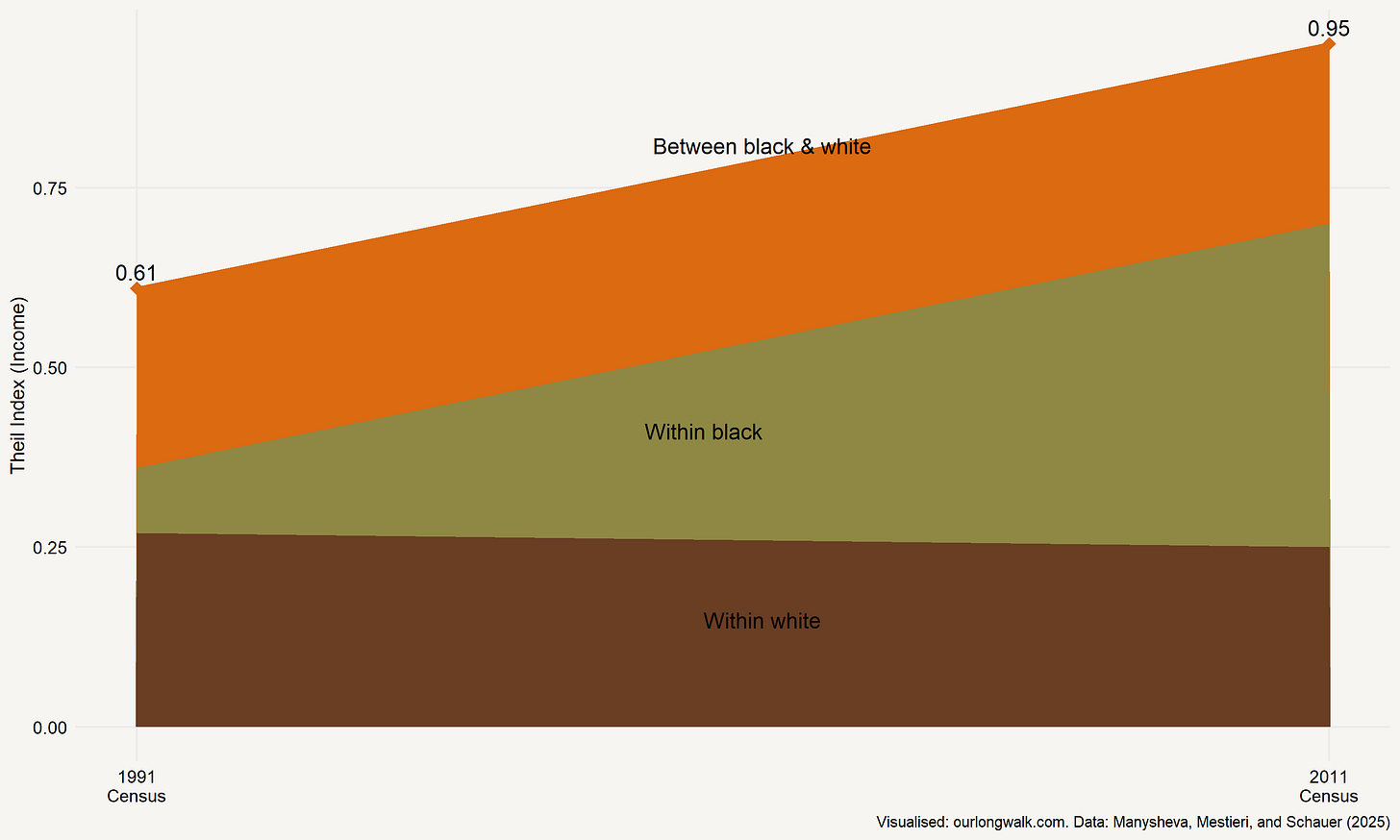

A new working paper by Manysheva, Mestieri, and Schauer documents that within-group inequality among black South Africans has increased sharply since the end of apartheid. By contrast, the gulf between racial groups – the central organising principle of apartheid – is steadily narrowing and is projected to continue shrinking in the years ahead. In practical terms, as shown in the graph below, if every white South African left tomorrow, the Gini coefficient would look much as it did at the end of apartheid. Sachs ignores this transformation entirely.

When he does address policy, the omissions become even more telling. Sachs writes that Black Economic Empowerment has ‘made modest improvements, but the South African private sector remains overwhelmingly white in its senior management and ownership structures’. Yet he offers no explanation for why BEE has failed: not a word about the incentives, blockages, or unintended consequences that have hobbled its effectiveness. Instead, he leaves the reader to assume the explanation is simple discrimination.

The greatest gap in the paper, though, is Sachs’ refusal to reckon with state capture and institutional decay. The 2010s were marked by industrial-scale looting, the near-collapse of Eskom and Transnet, and a collapse in the credibility of the state. Yet ‘corruption’ is mentioned only in passing, at least once in reference to the private rather than public sector. To discuss South African economic policy in 2025 without confronting state failure significantly weakens his analytical framework.

What does Sachs offer as evidence? He leans heavily on an argument that successful growth requires an even initial distribution of productive assets and human capital. But this does not stand up to historical scrutiny. For one, economic growth does not require a society to be perfectly equal at the start. Consider the record: Chile, Poland, Turkey, and Malaysia, all countries that suffered deep historical traumas, high Gini coefficients, even periods of brutal autocracy. All managed to grow rapidly and deliver better lives for millions. Look at the chart: in 1982, the year I was born, all these countries were poorer than South Africa. But since then, and especially since 2010, they have pulled ahead. The gap between them and South Africa today is tragic because it is avoidable.

The fundamental truth is that radical redistributive policies will take South Africa further away from the economic growth that is desperately needed. Growth matters deeply. The absence of growth is felt most by the poor, whom redistribution alone cannot sustainably uplift.

What, then, should we do? Here, Sachs’ silence is again telling. One third of South Africans, and most of the very poorest, still live in the former homelands with usage rights but no formal ownership of land. Sachs overlooks these regions entirely, as if the geography of poverty could simply be left out of the policy debate. Any serious effort to address poverty and inequality must begin there. The same holds in urban areas, where most township residents have insecure tenure. Public sector housing is stymied by a construction mafia, while private sector developments face significant delays from everything from historical societies to a dysfunctional deeds office. There is a strong, well-documented link between effective land registries, an indicator for sound property rights, and economic growth. Yet Sachs is silent on this as well.

He does, to his credit, note that monopoly and concentrated industries are a problem. But he fails to mention the obvious solution: lower the regulatory barriers, including BEE compliance rules, audit regulations, and sector-specific red tape, that stifle entry and competition and keep new, often black, entrepreneurs out. If you want more dynamism, you need to make it easier for people to start and grow businesses. It really is that simple.

In short, Sachs’s paper is unmoored from both economic theory and historical evidence. It reads as if written to justify a political position, not to advance our understanding. The job of the National Treasury, where Sachs once made an admirable contribution during the worst days of state capture, is already difficult, with many demands upon an ever-shrinking tax base. Pieces like this only make their job more difficult by giving intellectual cover to ideas that will not work.

What South Africa needs is not more high-minded theorising about redistribution, but leadership willing to do hard things. The path out of poverty is growth, and growth that reaches those who have been left behind comes not from endless new policies, but from the basics: secure property rights, effective schools and clinics, working infrastructure, and rules that allow new entrants to compete. We know what works because the rest of the world has shown us.

An edited version of this article was published on News24. Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. The image was created with Midjourney v7.

Sachs underplays the point that asset redistribution SA style throuh state capture, corruption and muddled leadership enriches a favoured few, curtails investment in human capital and essential services for the poor, thus adding to the widening of the income gap.

It would be instructive to put arrows on key dates on the graph. The decreasing GDP until 1994, the flattening after Zuma elected in 2009. It highlights that the problem with SA GDP growth is political!