Fourie vs StatsSA

The battle over definition and data in South Africa’s unemployment crisis

It’s not every day that the measurement of economic statistics is at the center of a public debate in South Africa. But when soon-to-retire CEO of Capitec Gerrie Fourie suggested in off-the-cuff remarks that South Africa’s true unemployment might be closer to 10% than the official 32.9% figure published by StatsSA, he set off a storm of controversy, drawing economists, policymakers, business leaders and journalists to weigh in on what, and who, should really count as ‘employed’ in South Africa.

Let’s begin with what Fourie (no relation) said:

What is interesting is when you look at the unemployment rate, we talk about 32%. But StatsSA doesn’t count self-employed people. I really think that is an area we must correct. The unemployment rate is probably actually 10%. Just go look at the number of people in the township informal market, who are selling all sorts of stuff, who have a turnover of R1,000 a day.

To grow SA, we need to understand what is happening there [in the informal market]. If we really had a 32% unemployment rate, we would have had unrest. If you go to the townships, most people have back-rooms to rent out, everyone is doing something. If we are talking job creation, let’s go out and encourage these entrepreneurs.

Labour economists fired the opening salvo. In a letter to Business Day, UCT economics professor Andrew Kerr acknowledged that there are legitimate concerns about the QLFS – such as poor quality data on earnings and the puzzling fact that employment numbers are often higher in the General Household Survey than in the QLFS – but insisted, correctly, that the claim StatsSA does not count the self-employed as employed is simply not one of those concerns. Sadly, his otherwise reasoned letter closed with a patronising put-down: ‘The Capitec CEO should stay in his lane and confine his pronouncements to topics such as borrowing and lending.’

Others jumped on the bandwagon. Author Jonny Steinberg said Fourie had exposed his ‘intellectual laziness, born from overconfidence’. Former statistician-general Pali Lehohla called Fourie a ‘random businessman who profits from black communities’ who make ‘comments on a system he clearly doesn’t understand’. Economics columnist Duma Gqubule concluded that Fourie should withdraw his statement because it ‘minimises the pain of 12.7-million unemployed people in SA’.

So much for encouraging public discourse.

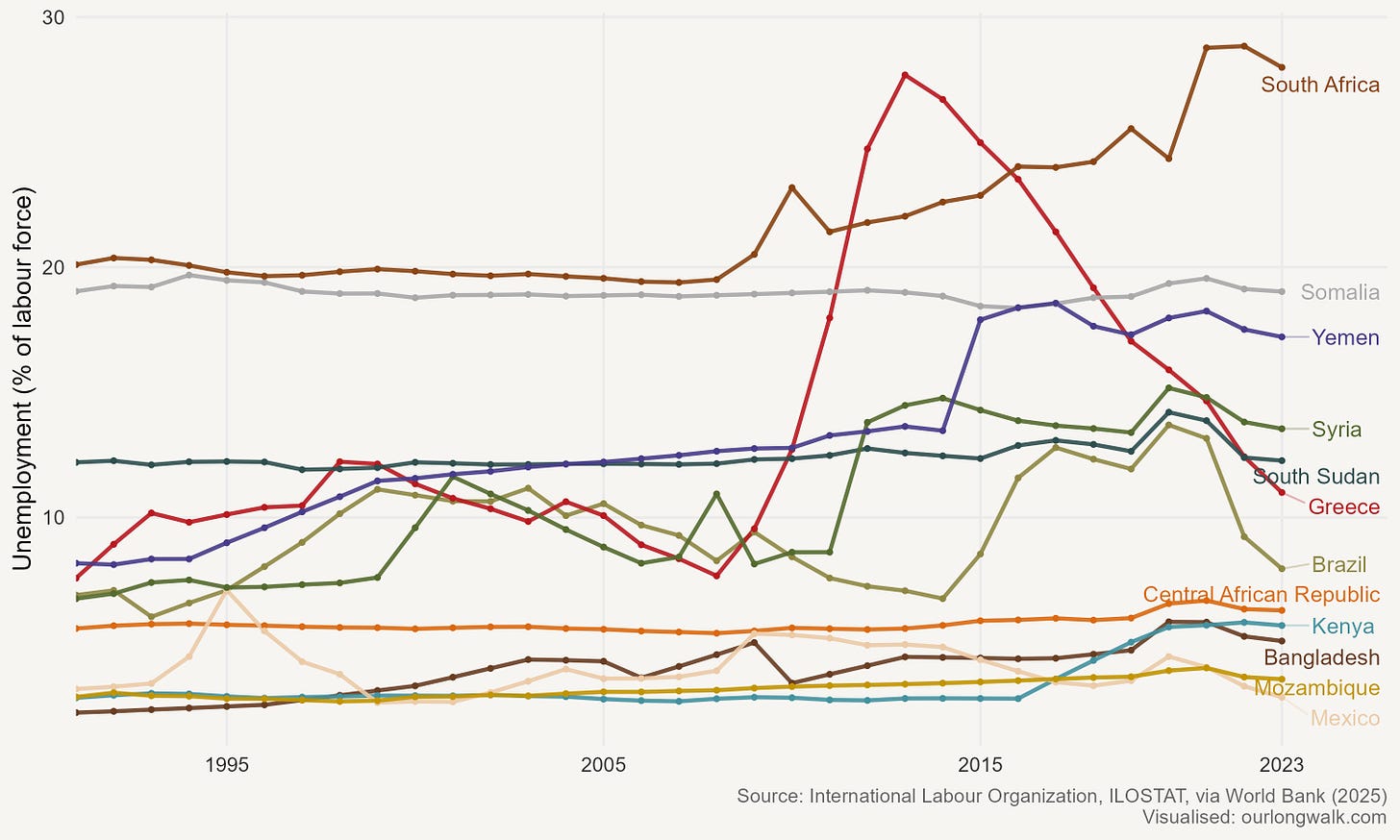

Yet consider the graph below. These are the unemployment rates for a set of countries in the world. South Africa, as you’ll notice, is a massive outlier; our unemployment rate, according to the ILO, was 28% in 2023, more than double that of Somalia and Yemen. Greece overtook us for a few years when its GDP shrank by a quarter after the global financial crisis, but it recovered to its usual 11%. Brazil at 8%, Kenya at 5.7% and Mexico at 2.8% all have rates that are barely a fraction of ours, making South Africa’s position not just unusual, but almost incomprehensible by global standards.

At the risk of a lane violation, I have to ask: is this really plausible?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Our Long Walk to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.