No rules

Fiscal rules don't cause economic growth

This is a free post from Our Long Walk, my blog about South Africa's economic past, present, and future. If you enjoy it and want to support more of my writing, please consider a paid subscription to the twice-weekly posts, which include my columns, guest essays, interviews, and summaries of the latest relevant research.

If your friends have overstayed their welcome at your next dinner party, turn the conversation to fiscal rules. Better yet, try ‘fiscal consolidation’. They’ll get the message and soon find their way to the front door.

Fiscal rules are a great way to bring a party to an end, both at the dinner table and for politicians who hope to spend their way to victory in the next elections. They essentially impose a limit on government spending, debt or deficits, usually set as a numerical target. The idea is that they remain in place despite changes in government, ensuring predictable policies that underpin growth.

Dive a bit deeper, though, and fiscal rules become, well, messy. Different types of fiscal rules tackle various aspects of fiscal policy. Germany’s ‘debt brake’, for instance, limits its structural deficit to 0.35% of GDP to maintain debt control. Chile, with a revenue rule, saves extra copper revenue to stabilise finances during low export periods. The EU’s budget balance rule, capping deficits at 3% of GDP, aims to limit borrowing. Each rule has a unique focus, but all share the goal of promoting fiscal health.

Fiscal rules are often implemented to stop government overspending during elections. Brazil’s fiscal rules, introduced after repeated debt crises, exemplify this. Rules like a spending cap also signal to investors that the country is fiscally disciplined, potentially lowering borrowing costs and boosting confidence in its economic management. By controlling spending, these rules help create a stable foundation for long-term growth.

South Africa already has a spending ceiling that supposedly caps government expenditure growth, though this has not prevented our debt-to-GDP ratio from increasing. That is why, in March, Minister Enoch Godongwana proposed a fiscal rule to address our growing debt. In April, Era Dabla-Norris, the IMF’s Deputy Director for Fiscal Affairs told a news briefing that ‘a debt ceiling could be useful in improving expenditure efficiency’.

Not everyone agrees. Many in the ANC and its alliance partners resist spending limits. Sure, some of them would not like to see the party end. But others make a more solid argument: fiscal rules can sometimes be too rigid, constraining necessary investments or responses to unexpected challenges. Germany is a case in point.

So why impose a rule that binds? ‘Answer: signalling’ says Claire Bisseker in last week’s Business Day. ‘In South Africa’s case, where there is a disconnect between the fiscal discipline sought by the Treasury and the expansive policy agenda of politicians, a fiscal rule would declare, not just to markets and investors but to the rest of the government and political parties, including the ANC’s rank and file, what the limits are.’

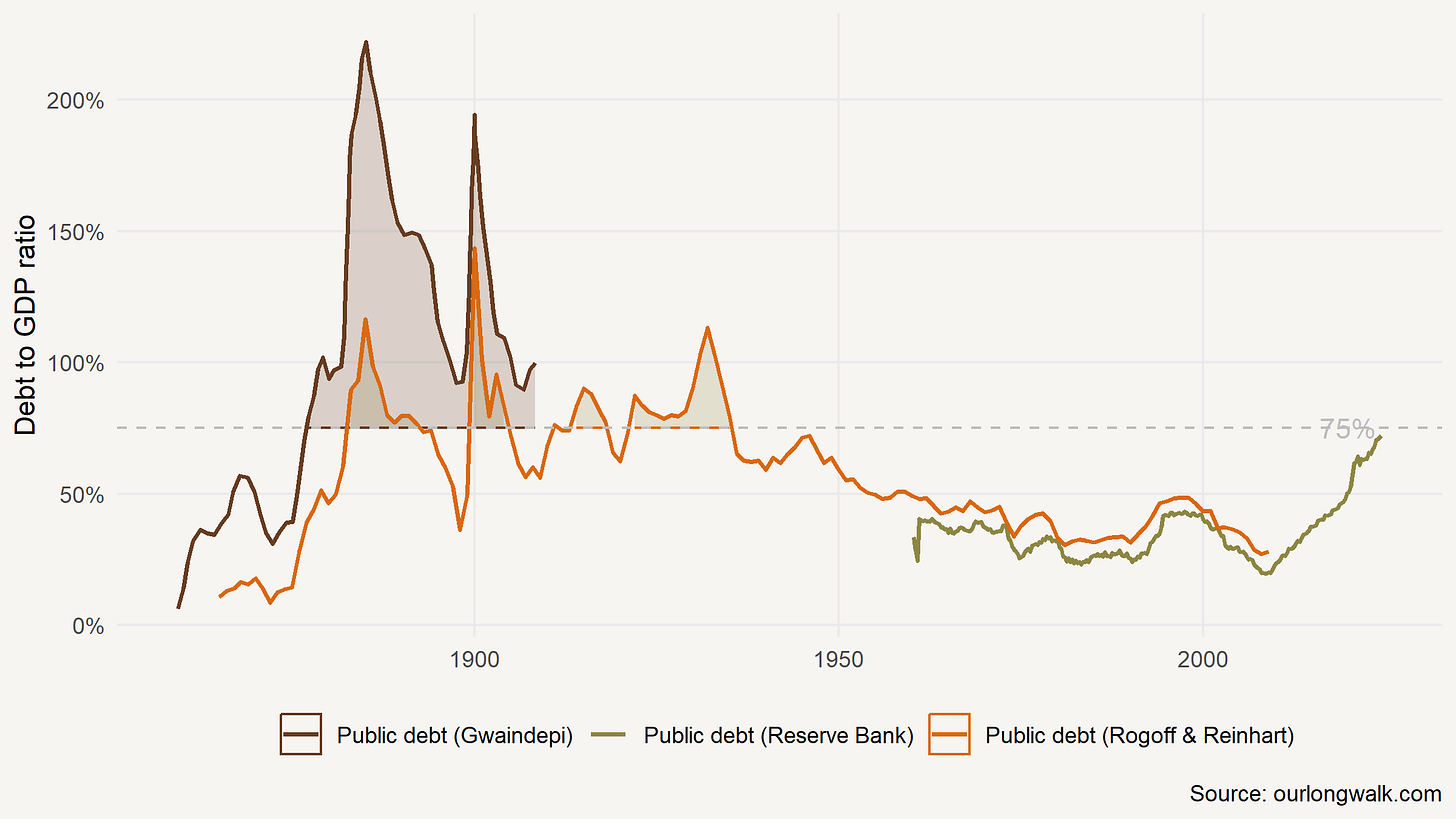

What those limits are, though, remains unclear. History can help. Many think South Africa’s debt-to-GDP ratios are at unprecedented levels. But consider the figure above, which plots, using three different sources of data, the debt-to-GDP ratio for the Cape Colony between 1865 and 1909 and South Africa from 1910 to today. Sure, since the 1940s, our debt-to-GDP ratio has not exceeded 75%, but before then, it had exceeded it in almost all years in the twentieth century. When the Cape Colony was building railways at a frantic pace, the debt-to-GDP ratio often exceeded double that. So, too, during wars.

The point is not simply about having room to increase our debt ratio; it’s about the purpose behind the borrowing. Are we borrowing to pay cadre salaries? That seems like a path to financial ruin. Are we investing in a new deep-sea port to make South African exports competitive? That’s better.

In short, signalling seems to be a high price for giving up flexibility. Stellenbosch University’s Krige Siebrits, who tackled the topic of fiscal rules in his PhD, agrees:

“There are two distinct ways to think about the purpose of fiscal rules. The first is that of binding constraints that prevent governments from behaving irresponsibly by accumulating too much debt. The second is that of mechanisms to realise governments’ fiscal goals by signalling their commitment to sound fiscal policy and anchoring expectations about the future course of fiscal policy. My reading of the international evidence is that rules have limited value as binding constraints, and it is not clear to me why they would serve this purpose better in South Africa than elsewhere. For example, would a debt rule have prevented the increase in South Africa's public debt-to-GDP ratio since 2010? And would future South African governments regard fiscal rules adopted by the present administration in, say, 2025, as binding on them too?”

Let me venture a guess: no.

“The case for rules as commitment devices seems stronger to me, but that argument should be qualified in two ways. First, rules introduced for this purpose are unlikely to be credible unless political will to maintain fiscal discipline clearly exists. Thus, it would have to be clear that the South African government as a whole is committed to the rules, not just the fiscal policymakers. Second, numerical rules are not the only mechanisms to anchor expectations about fiscal outcomes. In principle, a high degree of transparency in fiscal policymaking, which South Africa has had since the late 1990s, can do so as well. Adding rules to the policymaking framework will complicate fiscal policymaking (most notably when shocks hit the economy), and I would argue that serious thought should be given to exploring ways to strengthen the anchoring potential of existing institutions before rules are introduced.”

That’s right. Fiscal rules are not the panacea they are made out to be. How did the Cape Colony solve its high-debt problem? Economic growth. What explained the remarkable decline in South Africa’s debt-to-GDP ratio after the 1930s? Economic growth. How did we reduce our debt-to-GDP ratio from 50% in 1994 to 27% in 2007? Economic growth.

Fiscal rules do not inherently generate economic growth. South Africa’s expenditure ceiling may have helped stabilise public finances but did little to address underlying economic challenges like low productivity or high unemployment. Fiscal rules are tools of restraint rather than engines of expansion.

Let’s instead shift the conversation to what’s really needed to grow our economy. The reality is that achieving poverty-alleviating growth requires a lot more than a simple rule. It requires making much tougher political decisions that lay the groundwork for future productivity, like upgrading infrastructure, improving state capacity, reducing red tape and fostering innovation.

A strong economy, like a good party, thrives on freedom, not strict rules.

An edited version of this article was published on News24. Support more such writing by signing up for a paid subscription. The images were created with Midjourney v6.