De(con)structing mining

Job creation or job destruction? Wages will rise, but jobs will fall.

What South Africans should realise is that the mining industry will contribute little to economic growth of the future. Yesterday, The Economist wrote about the bleak future for South Africa's mining industry. My first reaction: why is that such a bad thing?

Let's use a production possibilities frontier to map all the possible production options for an economy (let's say, in this economy, mining and manufacturing are the only two products being produced). If we'd like to produce more mining products - if we already use all our productive resources efficiently - we'd have to give up something else, in this case, manufactured products. In other words, the more mining we produce, the less of everything else. This is known as opportunity costs. You may argue that the South African economy is not producing at efficient levels: just consider the massive unemployment (which I've written about before), estimated to be between 20-40%. With all these unemployed workers, we could produce more mining without having to incur the opportunity cost of reducing producing elsewhere.

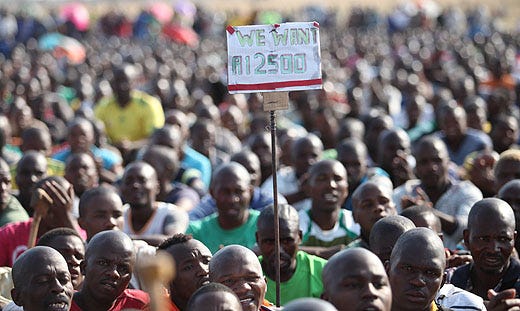

But there are two problems with this: those 20% (let's be optimistic) workers that are unemployed, are probably unemployable. They are not located close to cities (or mines) where jobs are more easily available. (Because of South Africa's warped spatial segregation during Apartheid, even if these workers live in cities, it is still expensive to get to work.) They are not well educated or trained (rock-drill operators isn't anyone's forte; if it was, the Lonmin workers won't be able to earn R 11,200 per month which place them in the top 20% of South African wage earners). It's also not only about labour. Deep-level mining is extremely capital intensive, and it's becoming more so. Except if all this capital is obtained from external sources (which will also come at the cost of other sectors: foreign investors will demand Rands, appreciating the exchange rate, making our exporters in other sectors less competitive), it has to come from domestic savings, savings that could have been invested elsewhere in the economy.

A second counter-argument might be that the mining sector produces a lot of stuff that other sectors use. This is only partially true. Firstly, the prices of the raw commodities are often set internationally, and because we are a minor producer of several mineral types, our production really doesn't affect the international price. This simply means that you can get coal from a South African producer or from somewhere else for pretty much the same price, so what is the benefit of producing it locally? In platinum, though, where we supply nearly 80% of the market, our production certainly will affect the price of platinum. But I'm not sure we add much value here: our largest exported product in 2011 was 'platinum, unwrought or in semi-manufactured forms', of which we exported more than $10 billion. Some of our production is used in making catalytic converters, for example, of which we exported $61 million, mostly to Japan and Germany. But, this is a tiny industry; compare that to the more than $467 million of grapes (also a raw commodity) exported 2011.

Mining is becoming more capital-intensive. It is not the way to address South Africa's unemployment crisis; the mining industry, to remain competitive, will lay off workers - as it should. (Incidentally, this is also why those workers that remain will be able to earn higher salaries - as capital replaces labour, those workers that remain become more productive. And why CEO salaries will increase even more.)

What will happen to those laid-off workers? In a market where wages are free to move (not South Africa), those workers that are retrenched by the mining companies will lower the wage rate in other industries, making these industries more competitive, and shifting South Africa's comparative advantage. (If wages cannot move, the unemployment rate will.) This is already happening: today, mining only composes 5.7% of South Africa's GDP, about four times smaller than financial and business services. South Africa's twentieth century economic success may have been built by cheap labour on the mines, but if we are to make a success of the twenty-first century, mining won't have a starring role. The sooner we realise this, the better.

I'm not saying that the mining industry will completely self-destruct. It won't, as long as there are lucrative opportunities to extract valuable minerals at relatively low costs (and, if you'd like to be cynical, profiteering politicians). But the South African mining industry is not the economic power that it once was. It's malaise is simply part of the process of creative destruction that all economies - if they want to grow - have to endure. Of course, not everyone shares this enthusiasm for relative decline, not least the people working in those industries, but we should remind ourselves that "destruction" is as necessary as "creative" for an economy to move forward.

*Photo by Taurai Maduna/Eyewitness News.