Colonialism misquoted

We have been quoting Lord Salisbury, only hindered by the small impediment that we never knew exactly where the original quotation came from

If you’re in or around Stellenbosch, join us on Friday at 15:30 for the 9th annual LEAP Lecture. Michael Muthukrishna (LSE) will discuss his research on ‘Cultural evolution and public policy’ in the Jan Mouton building, Room 3010. RSVP here.

This is a free post from Our Long Walk, my blog about South Africa's economic past, present, and future. If you enjoy it and want to support more of my writing, please consider a paid subscription to the twice-weekly posts, which include my columns, guest essays, interviews, and summaries of the latest relevant research.

Editing a book can be a humbling experience.

I made several errors in the first (Tafelberg) edition of Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom (2021), errors that I was happy to fix in the second (Cambridge University Press) edition. These included typos, one or two grammatical mistakes, and several missed references. The thoroughness of the CUP editorial team, I convinced myself, also ensured that there were no slip-ups in the second issue. It was as close to a perfect product as one could get.

But errors always slip in. Revising the chapter on colonialism in Africa in preparation for a second Tafelberg edition, out in January 2025, I came across a direct quote that I had failed to attribute to its original source. How it slipped through the CUP editor’s eyes I don’t know, but I was glad to pick it up before anyone else did and went in search of the original quote.

This is a post about the search for a single reference.

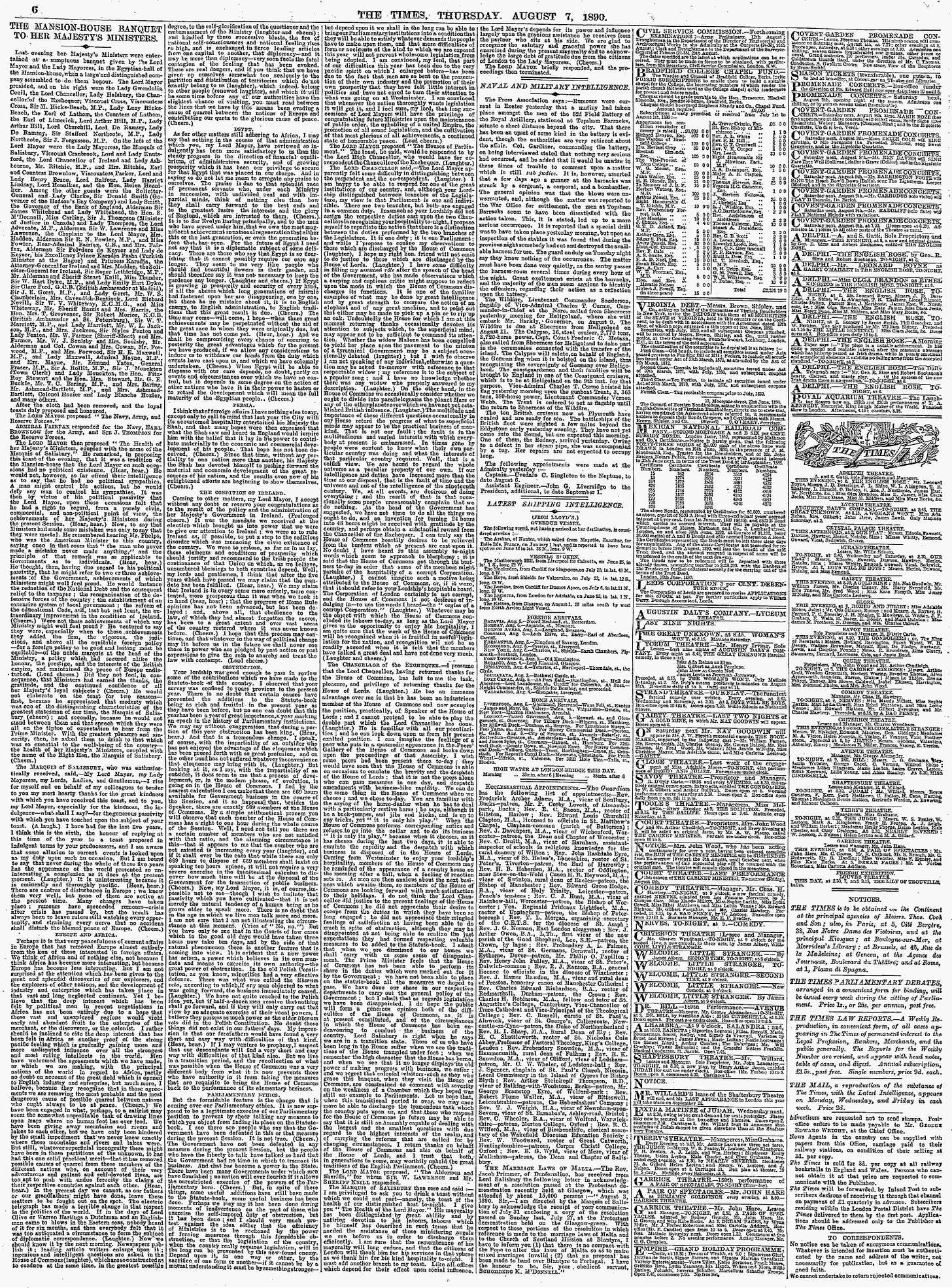

The reference was for one of the most famous quotations in all of African history, by Lord Salisbury after the Berlin Conference of 1884/1885, the meetings that initiated the Scramble for Africa:

We have been engaged in drawing lines upon maps where no white man’s foot ever trod; we have been giving away mountains and rivers and lakes to each other, only hindered by the small impediment that we never knew exactly where the mountains and rivers and lakes were.

The easiest way to find a quote is to Google it, which is what I did. I found many links. I clicked on the most obvious one, a paper by a famous African historian, and found a link to J.C. Anene’s published dissertation from 1970. I could not find a copy of the dissertation online. I then went to the next link. Now the reference was from another African historian, published more recently. I spent an hour going in circles, only to eventually stumble upon what I thought was the jackpot: a reference to the Geographical Journal of March 1914. Surely this must be it!

But no page numbers. Aah! I had to go and search for it myself. Luckily, JSTOR provides access. I opened the March issue. Nothing obviously jumps out. I searched through all the papers published that year on Africa, from a paper on Upper Senegal and Niger, to one on the Thonga Tribe in South Africa, from an archaeological survey of Nubia to the Tripoli enterprise about Italians in North Africa. Still nothing. Then the rest of the papers. Nada.

Like any good academic, I gave up and emailed one of my brilliant students with a request: Please find the damn reference.

A few hours later, Kelsey Lemon replied with the good news that she had indeed found the origin. But here was the surprise: The quote was significantly different from the one that I and almost every other writer had used. I’ll let Kelsey explain:

I Googled the phrase and opened every link, scouring every page Google had to offer. The shameful truth is that a LibQuotes page was the key. Beneath the (wrong) quote, the website listed the date and origin of the original: ‘speech at the Mansion House, August 1890’. After Googling variations on the phrase,

‘drawing lines upon maps’ + ‘Mansion House’ + Salisbury 1890

I came across A.L. Kennedy’s Portrait of a Statesman. In it, Kennedy reproduces the (correct) quote which he notes was reported in The Times. Seeing the discrepancy between his version and the other versions I’d come across, I needed to hunt down the original Times article. A new Times subscription and £1 down, there it was, hidden away in a forest of text:

We have been engaged in what, perhaps, to a satirist may seem the somewhat unprofitable task of drawing lines upon maps where no human foot has ever trod. We have been giving away mountains and rivers and lakes to each other, but we have only been hindered by the small impediment that we never knew exactly where those mountains and rivers and lakes were.

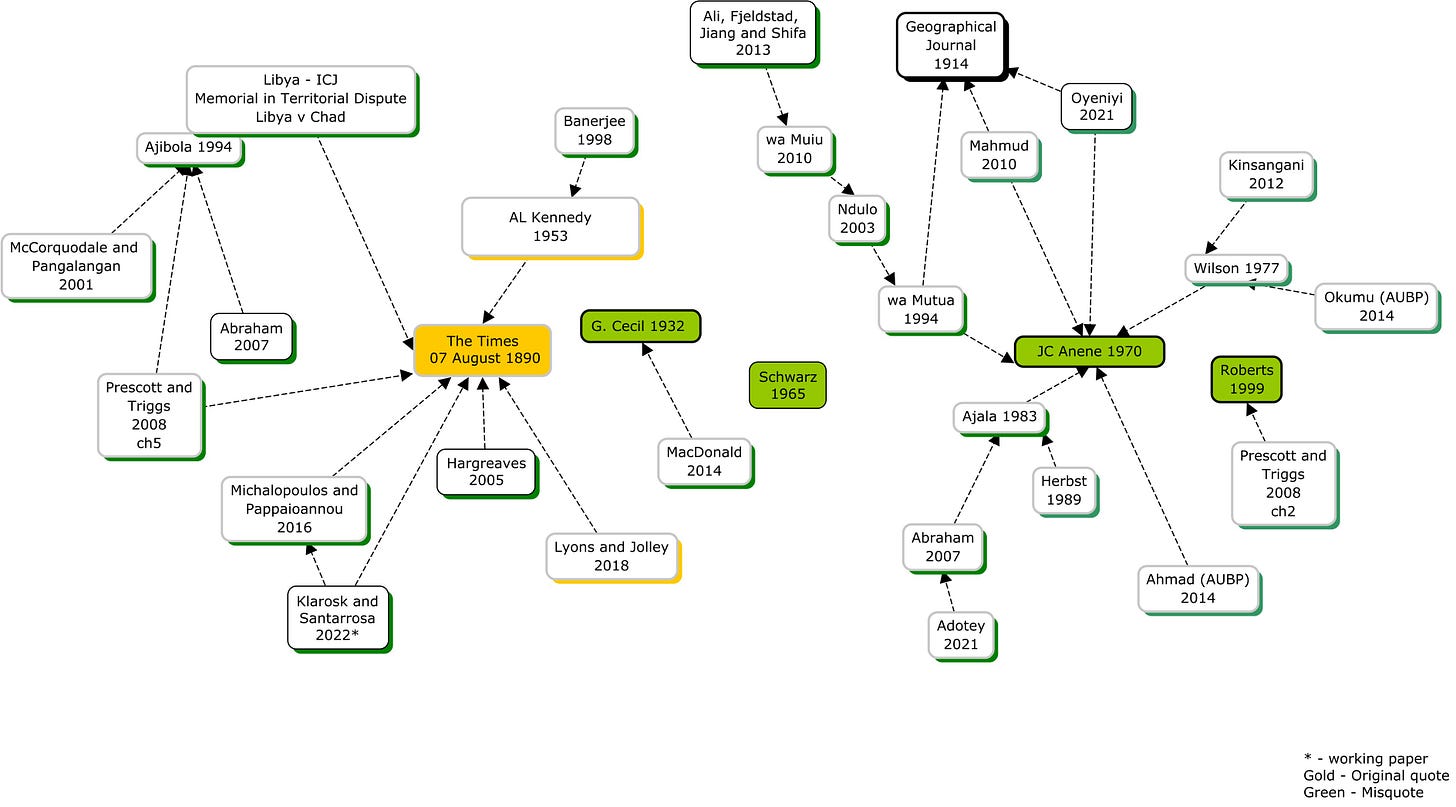

It’s worth looking at how often the original quotation has been misquoted. If you search for the correct version, you’ll find a discussion by Lyons and Jolley (2018) in the Handbook of African Development, which characterizes the quotation as “over-translated, poorly cited, and awkwardly reinterpreted”. Of the more than 30 publications we found that quote Lord Salisbury’s speech, only two gave the speech correctly. One of these is Lyons and Jolley’s chapter, which specifically cites it to correct the centuries-old mistake, and the other is Kennedy’s Portrait of a Statesman from 1953.

Of course, one cannot just leave it at that. What is the origin of this mistake, we wondered?

The earliest version of the misquotation we could find was by Salisbury’s own daughter – Lady Gwendolen Cecil – who published a four-volume book about her father: Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. JC Anene’s 1970 thesis, The International Boundaries of Nigeria 1885-1960, cited this version and became the source of the incorrect quotation that academics have used since. Here is Kelsey’s diagram depicting the quotations and their sources:

The above certainly doesn’t reflect well on historians (and social scientists). Errors abound. The Roman numeral XXCIII is an impossible number – perhaps an attempt to get to 43, the volume for the May issue? Things only get worse from there. Two publications I found used the quote twice but provided different citations for each. Likewise, a few authors cited the original Times article but again reproduced the incorrect version of the quote. Another used the misquote and included a misspelling of the word ‘trod’ as ‘tord’; a version which was itself replicated, misspelling and all. A fourth variation sees the error slip into the second part of the sentence for the first time with ‘...God will we have been giving away mountains, rivers and lakes to each other’.

But he most common difference between the original and the misquote is the substitution of ‘human foot’ with ‘white man’s foot’. As far as condemning the callousness of colonialism, the original quote is stronger than the misquote.

An element of the original which gets wholly left out is the parenthetical: ‘...what, perhaps, to a satirist may seem the somewhat unprofitable task…’. Those writing about this moment often refer to Salisbury’s sardonic humour and his gift for ‘British understatement’. Yet, is it precisely this self-awareness that is overlooked. In leaving this part of the quote out, the authors rob Salisbury of the opportunity to poke himself in the eye. As Kelsey rightfully observed, the quote is a powerful enough indictment of the man and the system he represents.

It’s astounding how many prominent historians, economists, and other social scientists got it wrong. But I shouldn’t be too dismissive – I did too, twice. Thanks to Kelsey, when Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom is published in January, it will only be the third published work to use the correct quotation and source reference. So science advances, sometimes frustratingly slowly, much like following a map drawn in the dark.

This is an edited version of my monthly column, Agterstories, on Litnet. Amid the decline of serious, balanced opinions globally and the reduction of Afrikaans in higher functions in South Africa, LitNet seeks to offer a space for those interested in current events and critical thinking. The image for this post was created using Midjourney v6.

Interesting read!

Pedantic note: XXCIII is 83 and unless that thesis didn't have that many pages, it's a valid Roman number (20 subtracted from 100 add 3). What was meant was probably XLIII. I happen to have read the Wikipedia page on Roman numerals recently and there it states that there wasn't a single convention for writing Roman numbers. There are more common ways, for sure, but not a single, standardised way (that's why you'll find e.g. IIII on watch faces and not IV).

Now that I've looked at the newspaper article in question, I have two comments to make, in defence of those bad old colonialists, re the 'no human foot' quote. Firstly, this article is a written version of a speech at a banquet. In 1884/5 they did not have recording devices to ensure accuracy. Errors may have been introduced by a reporter. Perhaps Lord Salisbury did say 'no white man's foot' and the reporter misquoted him. Secondly, at the top of the next column we read: '...the partition and distribution of territories which do not exactly belong to us, which indeed belong to other people...'. In fairness to Lord Salisbury, anyone really interested in this should read the whole article. And marvel at the attention span of Victorian newspaper readers.