An optimist’s guide to inflation in South Africa

Don't worry too much about overheating

In late July StatsSA announced the highest consumer price inflation (CPI) for South Africa for over a decade, at 7.4%. Notable increases were recorded for food like oils and fats (a whopping annualized 34.3%) and, following the massive hike in the fuel levy, petrol and diesel (36.8%). Those of us who like to buy oily takeaways at a drive-through should prepare for a budget readjustment.

The Monetary Policy Committee of the South African Reserve Bank reacted as expected on Thursday by raising interest rates by 75 basis points, the biggest increase in almost two decades. The Committee did this for two reasons: they are worried that higher inflation raises expectations of future high inflation. This would cause workers to demand much higher wages, which would further increase prices (because wages are often a large input cost). This could cause a vicious cycle, with prices spiraling out of control. A second reason is that higher interest rates in other parts of the world, like Europe and the US, make South African assets less attractive, which would depreciate the rand, further increasing prices.

‘So is this the beginning of a period of high inflation?’, you may ask. ‘Should we indeed adjust our inflation expectations upward (and therefore our wage demands) despite the attempts of the SARB to suppress them?’

Not necessarily. Sure, the early optimism that global inflationary pressures were just ‘transitory’, a fancy word for the temporary supply constraints created during lockdowns in China, turned out to be false: inflation, in South Africa and elsewhere, has continued to remain and even increased, as the recent figures show.

But there are signs in the global economy that this is indeed not your typical spiral towards hyperinflation. One sign comes, as always, from knowing history. Berkeley economics professor Brad de Long is the author of the soon-to-be-released and much anticipated Slouching Towards Utopia, a book about America’s twentieth-century development. In a recent column, he explains that there were several notable periods of inflation during the twentieth century. He describes each of them, from the first world war to the post-second world war economy of the 1950s to the period of stagflation during the 1970s, and then explains which of them best reflects our current situation. His answer? The shocks of 1947 and 1951 are the most similar because both were caused by supply constraints – the first in anticipation of the Korean war and the second due to supply bottlenecks.

What is important to note is that these two episodes did not lead to long-term high levels of inflation. Once the supply shocks had been addressed, price pressures relaxed. Workers did not demand higher wages because they expected that price increases would slow down. And they were right.

A second sign that we are not in a negative spiral is that some of the supply constraints are already easing. America is already reporting disinflation. (Disinflation is the decline in price increases, meaning that prices still go up but at a slower rate.) American economist Noah Smith reports five signs of disinflation. First, rapidly falling freight rates. Although they are not measured in CPI, they certainly affect input costs, especially for a country like South Africa. Second, commodity prices, bar coal, are falling. This is both good and bad for South Africa. It is bad because a large part of our tax revenue is derived from high commodity prices, but it is good because commodities are important inputs into the production of consumables. Third, Smith shows that rental prices in the US are increasing at slower rates. Rent is usually a big part of household budgets. Fourth, because of lower crypto prices, the demand for Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) has declined rapidly, and so have their prices. This should make semiconductor computer chips, an important input into many industries, more accessible and cheaper. In fact, this is exactly what executives from Hyundai Motor Co and fridge maker Electrolux announced recently. Finally, in the US, retailer inventories are rising. This often increases the likelihood of special discounts, which do, of course, reduce the price of goods. In short, there are optimistic signs that the factors that contributed to a sudden rise in global factors may be receding.

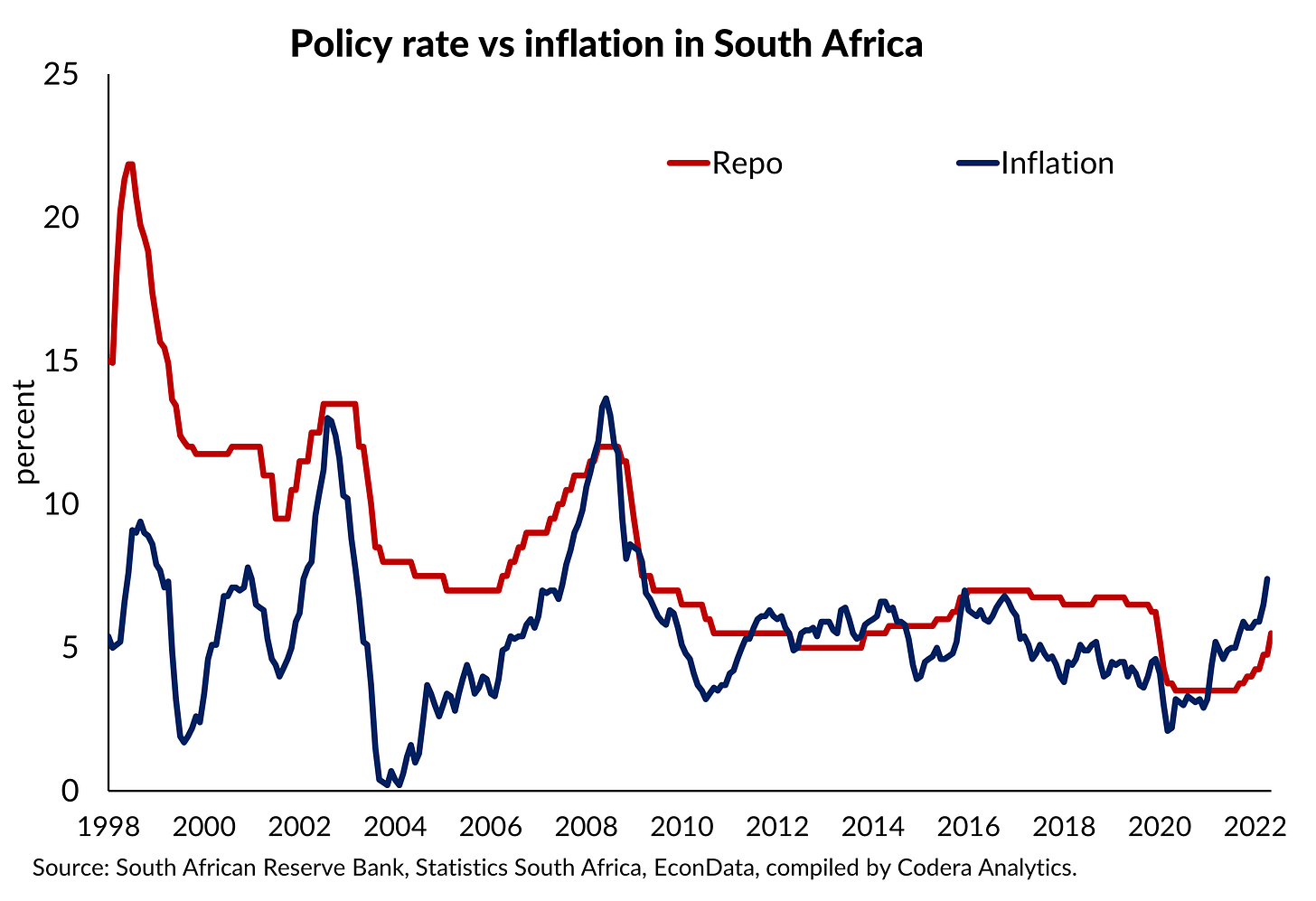

South Africa’s own recent history also provides two reasons for optimism. First, despite the 75 basis points increase, the repo rate today is still considerably lower than for most of the previous two decades. Second, as the figure shows, the two major inflation spikes in the last two decades, in 2002 and 2008, were short-lived. The SARB then responded accordingly, reducing rates as soon as there were signs of disinflation.

What is the pessimistic scenario? Well, if global supply constraints (including food and fuel shortages) continue, perhaps as a consequence of the ongoing war in Europe or persistent lockdowns in China or some new threat, then inflation expectations may rise to 8% or higher. This will push workers to demand higher wages and risk turning inflation expectations into reality. As the SARB tries to rein in this higher inflation, higher interest rates will only further reduce discretionary spending. A recession would inevitably follow.

The good news is that consensus inflation expectations are not yet above the 6% upper target set by the SARB. The Bureau for Economic Research reports inflation expectations of 5.6% for 2023, up from a previous estimate but still within range.

The SARB did the right thing to raise the repo rate in response to higher domestic inflation and global pressures. But both South Africa’s workers and the SARB would do well to learn from history not to push too hard in an environment where high inflation could be more of a temporary than a permanent phenomenon.

*An edited version of this article was first published on News24. Photo by Moritz Spahn on Unsplash.