A tale of two vineyards

Charles Dickens and the lessons from Cape wine

Jan Greyling and I have new research on eighteenth-century Cape Colony wine production. It is work based on 142,054 observations of burgher farmers and their enslaved workers. There are tables and graphs and statistics filled with stars. To those not interested in agricultural history (and even to those who are), it can be a decidedly dull read.

So, let me attempt something slightly audacious: a literary allusion to illustrate the results of our research. I’m not sure it will – or can – work, but, as with good research (and wine), experimentation is the only way to find out.

Here goes: Charles Dickens’s ‘A Tale of Two Cities’ exposes the stark contrasts and dualities of the late eighteenth century, the time of the French Revolution. Juxtaposing the cities of London and Paris, he explores the deep social inequalities and the transformational power of sacrifice and redemption. The book is all about the paradoxes of human nature, where love coexists with hate, sacrifice with selfishness, and hope with despair. The famous opening line, ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,’ encapsulates this theme, portraying a world filled with both beauty and brutality.

So what is the relevance of Dickens for Cape wine?

It is this: Cape wine farms, much like the two cities in Dickens’s novel, tell a tale of two sharply contrasting realities. On one hand, there is the remarkable wealth that wine farming created; on the other, the sobering account of slave labour, where the sweetness of the wine is tainted by the bitterness of injustice and coercion.

Our dry statistics help to illuminate this world. Utilising a comprehensive set of annual household-level tax censuses, containing 142,054 unique observations and 148 variables across 143 individual censuses, we examine wine output and yield estimates at the farm level in what is, to our knowledge, a first-of-its-kind insight into a pre-industrial, colonial, slave-based society.

The first wine was produced in Stellenbosch within a few years after its establishment in 1677. By the 1680s, farmers had cultivated almost 200,000 vines, and this figure catapulted to 1.2 million by the 1700s. Despite fluctuations, the growth in vines planted and wine production continued throughout the eighteenth century and, as the figure below shows, accelerated after British arrival in 1795.

However, as panel c demonstrates, despite the increase in production scale, wine yields remained essentially constant. The litres of wine produced per vine fluctuated between 0.36 and 0.41 litres, a surprising result, given the overall growth in wine output.

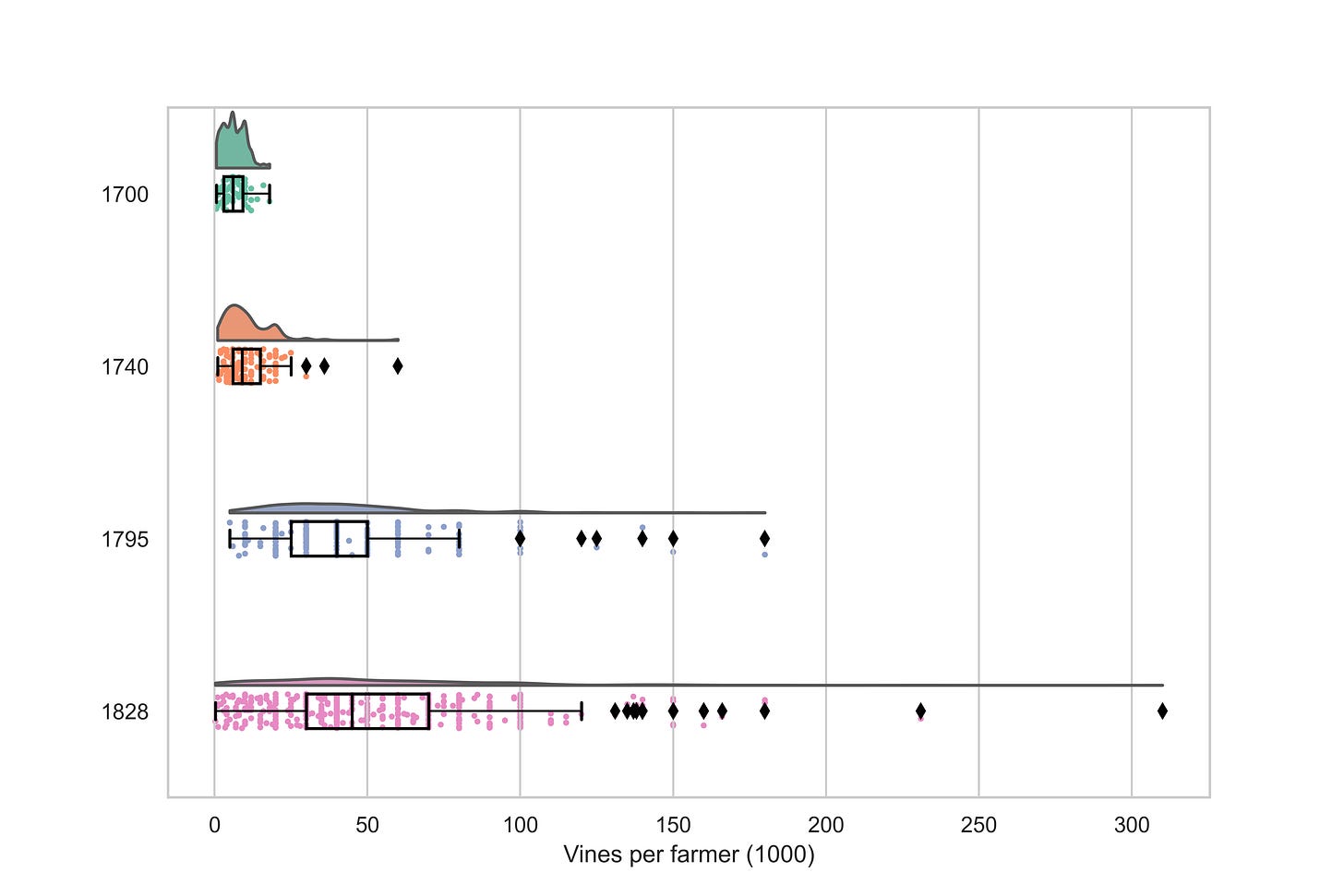

This is where our detailed farm-level statistics help. The figure below illustrates the increasing disparity in wine production between the average and the largest wine farmers over a specified period. In 1700, for example, the largest wine farmer possessed three times as many vines as the average farmer, but by 1828, this ratio had surged to 6.4 times. The volume of wine produced by the largest wine farmer increased even more quickly compared to the average farmer, increasing from 4.3 times the volume in 1700 to 23.3 times by 1828. This figure underscores the widening gap and inequality in wine production within the region.

Yet, as the figure below shows, despite the considerable expansion in vine cultivation and production of the largest farmers, the distribution of wine yields essentially remained constant, with only a negligible change observed. The stable trend may imply that there was no significant technological advancement affecting yields during the period observed.

So what explains the increase in scale, then?

We argue that it is closely tied to the expansion of slave labour. Larger farms benefited from increased (slave) labour productivity through specialisation and supervision. Ss forthcoming research by Tiaan de Swardt, Dieter von Fintel and myself demonstrates, there is ample evidence that some wine farmers transferred tacit knowledge, particularly in viticulture, to their enslaved workers. But coercion probably also plays a role; though they are expected to increase with the scale of operation, larger operations might distribute fixed supervision costs over more workers, reducing cost per worker and improving productivity.

The figure above shows this relationship clearly. Regression tests further revealed statistically significant effects of settler and slave counts on wine yield. Splitting slave labour into men and women showed contrasting correlations with yields, understandable in the context of the gendered division of labour on wine farms. However, no evidence was found for exponential increases in productivity with increased numbers of slaves, nor a meaningful shift in the relationship between slave labour and wine yields following the British arrival.

While the system of slavery led to increased wine production and ‘remarkable wealth’ for some – as my previous work has also demonstrated – it simultaneously created a barrier to innovation and advancement in wine farming techniques. Adam Smith, in his Wealth of Nations, noted that ‘slaves are very seldom inventive; and all the most important improvements, either in machinery, or in the arrangement and distribution of work which facilitate and abridge labour, have been the discoveries of freemen’. Slaves, being in a coerced position, had little incentive or ability to contribute creatively to the labour process. This suppression of innovation, as we argue, locked Cape wine farmers into a traditional and stagnant production system.

Only with the abolition of slavery in the 1830s did the opportunity for more substantial shifts in traditional methods begin to emerge. Wine yields would probably only meaningfully change after the arrival of the phylloxera disease in the late 19th century, which likely forced adaptation and innovation in viticulture practices.

The early history of wine at the Cape is, ultimately, a story of two realities. Yes, slavery enabled remarkable productivity and wealth, creating a wealthy burgher elite akin to the grandeur and opulence of one of Dickens’s cities. But it also entrenched a system resistant to change and advancement, mirroring the darker, more sombre tones of Dickens’s novel.

‘A Tale of Two Vineyards’ is a complex story that intertwines success and stagnation, innovation and inertia, in a narrative that stretches beyond literature to the fabric of economic and social life.

‘Stellenbosch wine output over more than a century (1680-1828)’ by Johan Fourie and Jan Greyling is currently under review for publication. It won the ‘best paper’-prize at the recent American Association of Wine Economists conference in Stellenbosch.