A most dangerous profession

On Hans Heese, genealogy and myth busting

This is a free post from Our Long Walk, my blog about the economic past, present, and future of South Africa. If you enjoy it and want to support more of my writing, please consider a paid subscription to the twice-weekly posts that include my columns, guest essays, interviews and summaries of the latest relevant research.

In March 1981, Humphrey Tyler wrote in the Christian Science Monitor for an American audience:

A couple of Cape Town academics who have sifted through church records, marriage registers, old deeds, and archives have produced further proof that vast numbers of the South African whites who support the racist ‘apartheid’ segregation policy are not pure white themselves.

The article quotes two young researchers from the University of the Western Cape – Leon Hattingh and Hans Heese – who report on their latest genealogical research:

Professor Hattingh said that some people had even accused him of taking part in a ‘liberal plot’ to oblige people to reconsider their views on race – ‘but this is nonsense’, he said.

Genealogy is a dangerous hobby; just like lawn bowls, it has one of the highest mortality rates in the world. Hans Heese, who passed away last month at the age of 79, would surely have had a chuckle at this joke.

But in the early 1980s, there was little to laugh about. Genealogy was politics. But before we go there, it helps to start the story from Heese’s own origin.

Hans Friedrich Heese was born on July 2, 1944, in Kamieskroon, as the son of Dr Johannes August Heese. Dr JA Heese was a principal in Uniondale and, thereafter, an expert assistant at the NG Church Archive. With the establishment of the Genealogical Society of South Africa on June 18, 1964, in Joostenberg, he was also a founding member and served as the first secretary. He would also gain particular renown for his book ‘Origin of the Afrikaner’ and later received the DF du Toit Malherbe Prize for Genealogy from the SA Academy for Science and Arts. His son Hans was to be the guest speaker at the 60th-anniversary celebrations of the GSSA later this year.

It was his father’s work that inspired Hans to further research on this topic. The Institute for Historical Research was established in 1976 at the University of the Western Cape, and Hans Heese joined them. The aim of the Institute was to make a scientific contribution to a better understanding of the historical background of race relations in South Africa.

In 1985, in a time marked by political change and violence, Hans published his controversial book, Groep Sonder Grense (later translated to Cape Melting Pot). With this research, Heese exposed the racially mixed origins of South Africa’s so-called white population more comprehensively and scientifically than anyone before him; he genealogically proved that many ‘white’ families, along with the so-called coloured population, descended from interracial unions between the European settler population, imported slaves from Africa and Asia, and the indigenous populations.

The book received severe criticism, and despite his calm demeanour, as his daughter Francisca also mentioned in her tribute, things were not always easy: Hans received several death threats after the book’s publication.

The fact that white Afrikaners had coloured and black ancestors was, of course, not really news. As Robert Ross, one of South Africa’s leading historians, recalls:

For me, with my connections to the Cape Town student left, what Heese did was in no way surprising – though we cheered him from the sidelines. My memory is that there were two groups of people for whom the Heese research had no particular novelty. These were the coloured middle class, shading into the white left. Thus, Sam Kahn (communist MP for Jeppe) is supposed to have given a speech in which he went through the descents of the various members of the cabinet (it was cut from Hansard, so it was said; it was undoubtedly based on the knowledge created by the Unity movement and so forth). The other group were the Cape Dutch elite, from the wine farms, etc, who knew what went on on their properties and had no problems with it.

The problem came from the Transvaal in this reading because the Transvaal Afrikaners had only their whiteness as the basis for their political dominance, and here in the twentieth century, the boundaries between black and white were maintained with a rigour that is rare in colonial societies, in particular settler societies.

I think that the importance of Groep Sonder Grense was very varied, from the ‘I always told you so’ (linked to some extent to the ‘at least we are all white’ [with the sub-text ‘and so we ought to be running the country’] of the Anglophones, to at the other end, ‘this is a slander of the upright Afrikaner nation’. It was, after all, Van Jaarsveld who got tarred and feathered, not Leonard Thompson.

Ross, of course, is referring here to the incident in March 1979, when a young Eugene Terre’Blanche and his associates lifted historian Floors van Jaarsveld off his feet during a lecture at UNISA and doused him with a can of tar and a sack of feathers. Van Jaarsveld’s lecture was about the Blood River vow. His argument was that the testimony of Andries Pretorius and his secretary Jan Bantjes held much more value than that of Sarel Cilliers, who had recorded his memories thirty years later on his deathbed. It’s not a topic that today would attract more than a handful of listeners.

And yet, following this incident, Van Jaarsveld repeatedly received death threats. He also survived an assassination attempt when a crossbow bolt shot through his study window and pierced the wall behind him.

Why can history unsettle us so? Early postmodern writers like Jean-François Lyotard helped us understand this. He criticizes the ‘grand narratives’ of history – les grands récits – traditionally used to legitimise power structures. For the Afrikaner community of the twentieth century, the grand narrative of racial purity was the legitimising force for apartheid policy. Hans Heese and his genealogical research – his family stories about where we come from – destroyed this grand narrative.

It was not just Hans’s archival research that made a difference, but also his willingness to publish it. The big chief of postmodernism, Michel Foucault, writes, for example, that ‘the purpose of history, guided by genealogy, is not to discover the roots of our identity, but to commit itself to its dissipation’. Stefan Berger, in a new book History and Identity, writes that Foucault calls explicitly for a variety of public, self-critical voices, people who are not afraid to speak against the power structures of the day. Such voices will make the ‘grand narratives’ more unstable until they ultimately collapse.

Now I wonder: What are the ‘grand narratives’ of today that could use some self-criticism? And who are the historians who, like Hans Heese, will go back to the archive to decipher these histories and question the stories we so complacently tell ourselves?

For the last few years, Hans and his friend Chris de Wit, along with me and my team, have been working on a massive project to transcribe the tax rolls in the Cape archives. The tax rolls were introduced in 1663 by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) to take an annual tax survey of all the free citizens. This was continued by the English and was eventually ended in the 1840s. Each year, every free Cape Colony family (and sometimes also mission station residents) was counted, with their number of children, Khoe and enslaved workers, as well as the number of cattle, sheep, and horses owned, and wheat, barley, oats, and rye sown and harvested.

The tax rolls give us a glimpse into Cape history that no historian has been able to access before. These records provide not just information on who the rich and poor were but also the reasons for their wealth and how prosperity was transferred across generations. When we combine these records with inventories, auction rolls, or slave records (in which Hans was naturally the expert), we can also tackle other ‘grand narratives’, such as the reasons for the Great Trek. (Perhaps a myth in need of busting.)

But I'll leave Chris de Wit to have the last word:

It was a languid early autumn day on Friday, March 8, and Hans and I were sitting under the trees at our favourite coffee shop for our monthly ‘coffee chat’, as had been the custom for the past few years. In the following hour or so, we would then let our thoughts take wide turns, our different youth years in the Klein Karoo where both of our roots are deeply and firmly anchored.

We were both working on the tax rolls of the Cape District from the 18th century and were also constantly trying to place the mass of data we were working on within a broader historical context. As the foremost expert and seasoned researcher of the Cape’s slave history, we exchanged thoughts on the seemingly contradictory phenomenon that slaves from the 1730s owned slaves themselves, as shown in these tax rolls. Were they freed through marriages, we wondered, or adoption of the Christian faith? Or perhaps they were bought to be freed? Perhaps they were exiles to the Cape? Or a widow who had inherited wealth? Those were precious moments with a great Cape historian and an even better friend.

‘A tree without roots is just a piece of wood’ is an African proverb that sums up the importance of genealogy well. With the passing of Hans Heese, a great tree has fallen, one that was willing to challenge and redefine the myths of a nation’s history by searching for the truth.

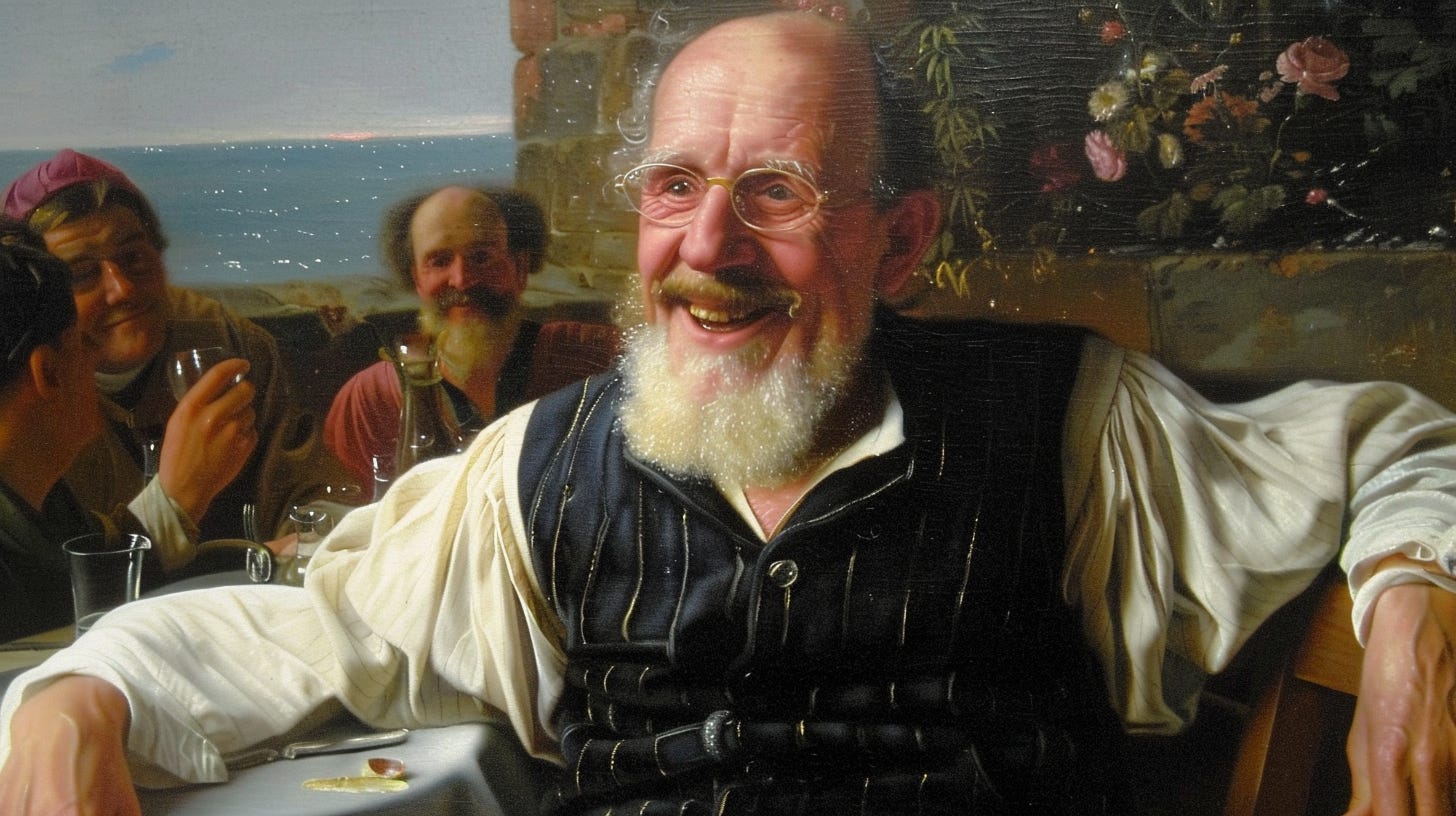

Thank you to Chris de Wit, Andrew Kok, Keith Meintjes and Robert Ross for their input. An edited version of this post appeared (in Afrikaans) in Rapport on 14 April 2024. The image was created using Midjourney v6.

A beautiful tribute to a pioneering historical demographer and also to the value of historical myth-busting. Thank you for giving so eloquent a tribute for those of us who did not know him.

Hans, unstinting in his kindness and willingness to share information. A true gentleman and fearless researcher. This article does him proud.